Most American Alpine Journal (AAJ) stories cover climbs from the prior year. But in some parts of the world, where January and February are prime for climbing—Patagonia, Antarctica, parts of Africa—we do our best to report the latest ascents. With that in mind, here are a few stories about recent climbs that will appear in the 2024 AAJ—plus one ski descent—from four different continents.

Fanny Schmutz follows the wild ice chimney just below the headwall on Cerro Torre’s Southeast Ridge. Photo by Lise Billon.

HISTORIC WOMEN’S CLIMB ON CERRO TORRE

On February 23, 2024, Lise Billon, Fanny Schmutz, and Maud Vanpoulle launched an attempt on the Southeast Ridge of Cerro Torre in southern Patagonia. This historic route avoids most of the bolts on the headwall placed by Cesare Maestri in 1970, and was completed in 2012 by Hayden Kennedy and Jason Kruk, who then removed more than 100 of Maestri’s bolts. The Southeast Ridge was freed, with variations, the same year by David Lama and Peter Ortner. The 800-meter route goes at around 7a+ C2 WI5 (or free at 7c). All three women had spent many seasons in the massif, and this year they traveled to El Chaltén with no other goal besides the Southeast Ridge. After a month of waiting, a good window arrived.

Despite difficult, snowy conditions on the start of the climb, the three women topped out on Cerro Torre after three days, completing the 13th ascent of the route since the Maestri bolts were removed. (Americans Tyler Allen and Scott Bennett summited via the same route on the same day.) The French trio’s climb of the Southeast Ridge was the first by women and is highlighted in the 2024 AAJ as part of our initiative to elevate coverage of cutting-edge ascents by female teams. (See “State of the Art: Expanding the Coverage of Women’s Climbing in the AAJ” in the 2020 edition.) Lise Billon wrote the story of the 2024 climb, and you can read it at the AAJ website now.

Adam Fabrikant descending Third Ledge on the north face of the Grand Teton in March 2024. Photo by Sam Hennessey.

WILD TETON DESCENTS

Sometimes great stories take time—we started work over two years ago on a history of ski alpinism in the Tetons with ski writer and producer Jason Albert. For AAJ 2024, Albert paired with IFMGA guide and big-mountain skier Adam Fabrikant to complete our “Recon” feature on the Tetons, but not without some last-minute additions. One of these was Fabrikant’s second ski descent of the north face of the Grand Teton with Sam Hennessey; the two descended the face in March 2024, about a month before the AAJ headed to the printer. This roughly 2,500-foot face was first skied in 2013 by local guides Greg Collins and Brendan O’Neill. Although many rappels were required to negotiate the complex line, Hennessey said the ski route was far from contrived: “Honestly, the north face has some amazing skiing in an outrageous position. We thought it was an excellent day of skiing.”

The north face descent made it into the upcoming AAJ, but then, in April, Fabrikant, O’Neill, and Michael Gardner teamed up for a massive link-up that instantly put our story out of date: Their “Enduro Traverse” linked the full southern Tetons skyline on skis, from Buck Mountain to Teewinot. As Fabrikant presciently wrote about the Tetons at the end of the “Recon”: “‘Skied out’ isn’t part of the vocabulary here.” Stay tuned for his AAJ report on the Enduro Traverse.

By the way, if you’re a fan of ski alpinism, be sure to check out The High Route, an excellent website and podcast on backcountry skiing produced by Jason Albert, co-author of the “Recon” in AAJ 2024.

Above: Nathan Cahill working on the route Dez Mangas at Serra da Leba, Angola, later led free at 5.11c. Photo by Diogo Rebelo. Right: a sandstone headwall floating above the mist at Fenda da Tundavala. Photo by Nathan Cahill.

THE SANDSTONE OF SOUTHWEST AFRICA

American climber Nathan Cahill has spent recent years helping to develop the climbing of Angola, a nation in southwestern Africa that has spectacular granite, conglomerate, and sandstone cliffs. In February 2024, Cahill traveled to the Huíla Plateau, site of Angola’s second-largest city, Lubango, to explore sandstone walls that rim the plateau. A highlight, described in Cahill’s report for the upcoming AAJ, was Serra de Leba, a deep canyon west of Lubango, where he put up a few short routes and a six-pitch 5.10c. Many unclimbed routes await. In a few months, Serra de Leba will be the site of the first Angola Climbing Festival (August 16–25), hosted by Climb Angola.

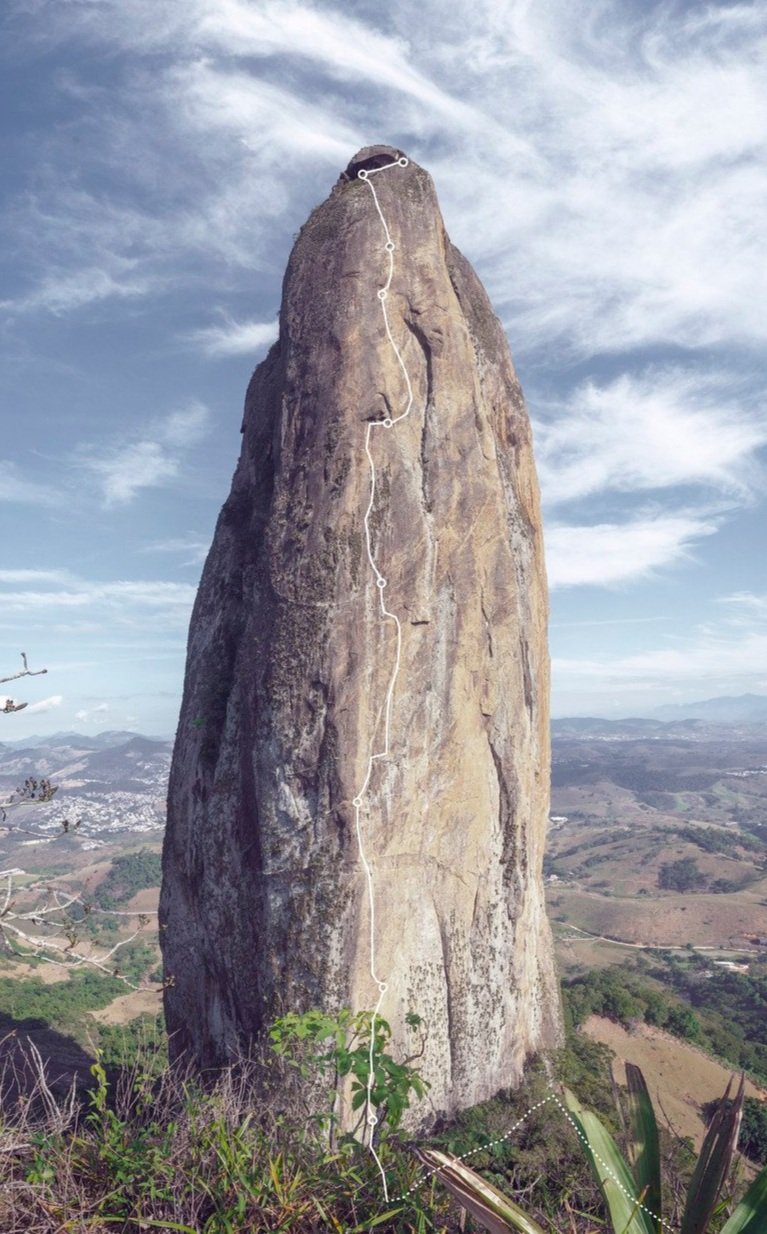

FIRST FREE ASCENT OF PICAFLOR IN COCHAMÓ

Hayden Jamieson pulling the crux on “The Strenuous V4” pitch (5.13+). Photo by Ian Dzilenski.

Who doesn’t love a good story of perseverance? A last-minute addition to this year’s AAJ tells a great one. American climber Hayden Jamieson spent two seasons in the Cochamó Valley of Chile on a quest to free Picaflor, a 24-pitch route up Cerro Capicua, first climbed in 2017 at 5.10+ A1. In January 2022, Jamieson and friends freed all but a single crux of the 1,050-meter route: a desperate slab sequence on pitch 20. “I had invested around ten days of work into pitch 20 and deemed it possible, but just barely,” Jamieson wrote in his AAJ story. “I knew that I’d need to improve my climbing level if I wanted to stand a chance at freeing Picaflor, so for the next two years I trained with that specific intention.”

Jamieson returned in January of this year with Jacob Cook and Will Sharp, and for five weeks the trio worked the route. At some point, Sharp spotted a potential variation to the crux slab traverse that had shut down Jamieson in 2022. “Despite being ‘easier,’ this pitch still clocked in at around 5.13+, and we gave it the tongue-in-cheek name ‘The Strenuous V4,’ ” Jamieson wrote.

On February 23, the trio began a seven-day push: Each climber led the route’s two 5.13+ cruxes, and they split the other leads evenly, with everyone freeing every pitch. Jamieson’s inspiring story for AAJ 2024 is available now at our website.

FIRST ASCENT (AND SKI DESCENT) IN ANTARCTICA

In January 2024, Antarctica guide Phil Wickens led a team of six aboard the yacht Icebird to make ski ascents and descents on the Antarctic Peninsula. On January 14, the team landed on the east coast of Liard Island and traversed to the unnamed glacier that flows northeast from Mt. Bridgman, the highest point of the island (around 1,410 meters). The following day, they made the first known ascent of Bridgman, via an improbable-looking line up its east face, and then enjoyed the 4,500-foot ski descent back to sea level. Wickens’ report is at the AAJ website.

Descending Mt. Bridgman on Liard Island, along the Antarctic Peninsula, after the first ascent. Photo by Phil Wickens.

The Line is the newsletter of the American Alpine Journal (AAJ), emailed to more than 80,000 climbers each month. Find the archive of past editions here. Contact Heidi McDowell for sponsorship opportunities. Got a potential story for the AAJ? Email us: [email protected].