Wild as it may seem, every year we publish at least one report of a climber getting their knee stuck in an offwidth crack. Sound crazy? It happened to Martin Boysen on Trango Tower and more recently Jason Kruk on Boogie Till You Puke.

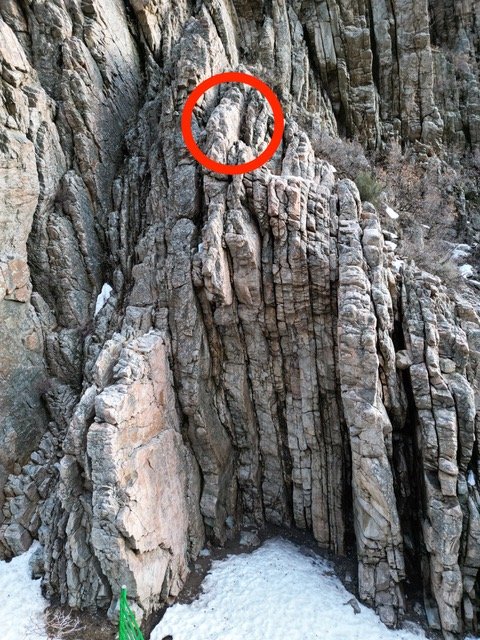

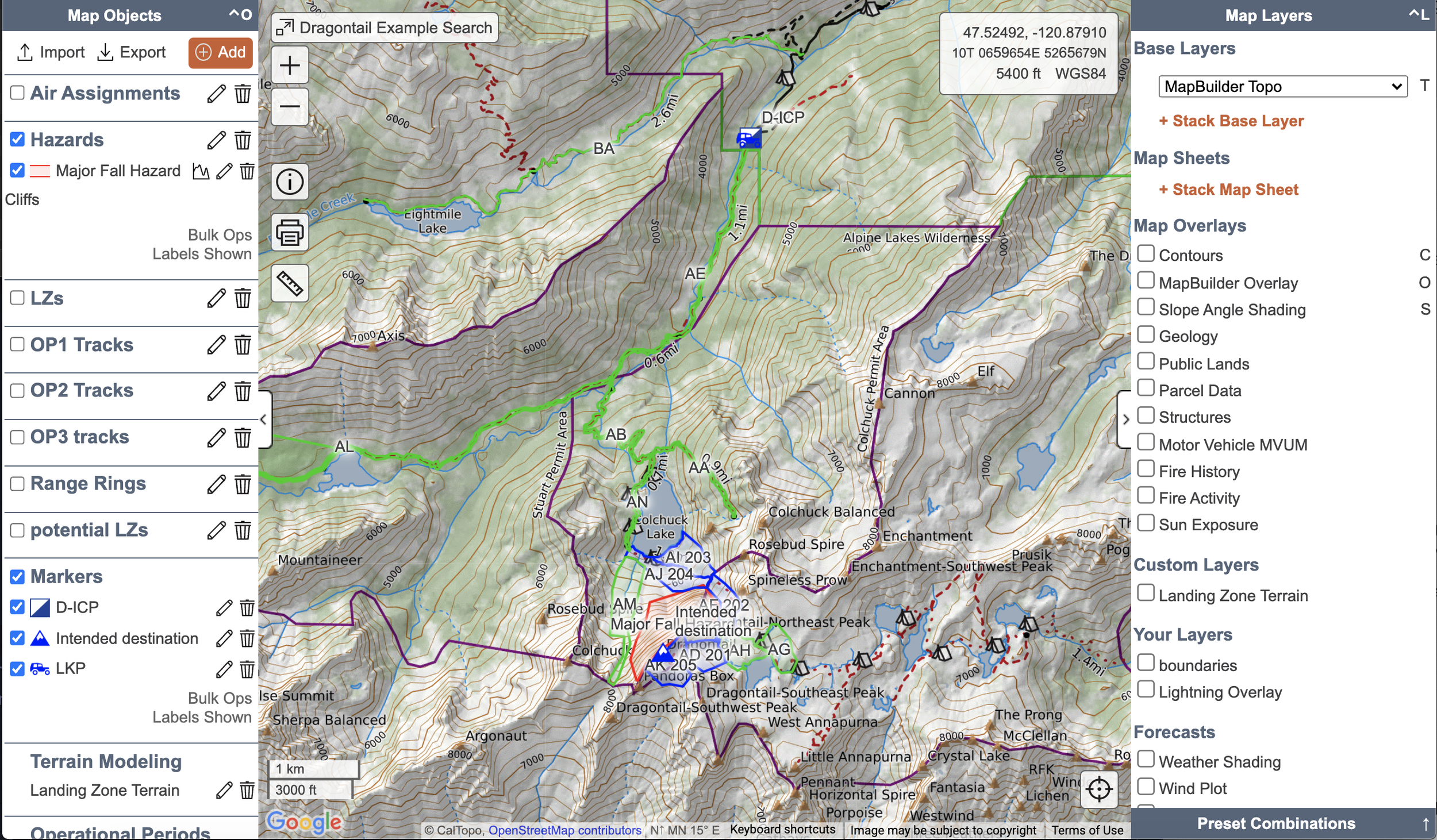

Queen Victoria Spire in Sedona, Arizona, was the scene of a stuck knee incident in 2023. Photos by Xander Ashburn | Wikimedia.

The final section of the second pitch of the Regular Route (III, 5.7) on Queen Victoria Spire. This four-inch crack trapped a climber on her first outdoor climb. Photo: Chris Thornley/Climbing Magazine

Knee Stuck in Crack

Sedona, Queen Victoria Spire

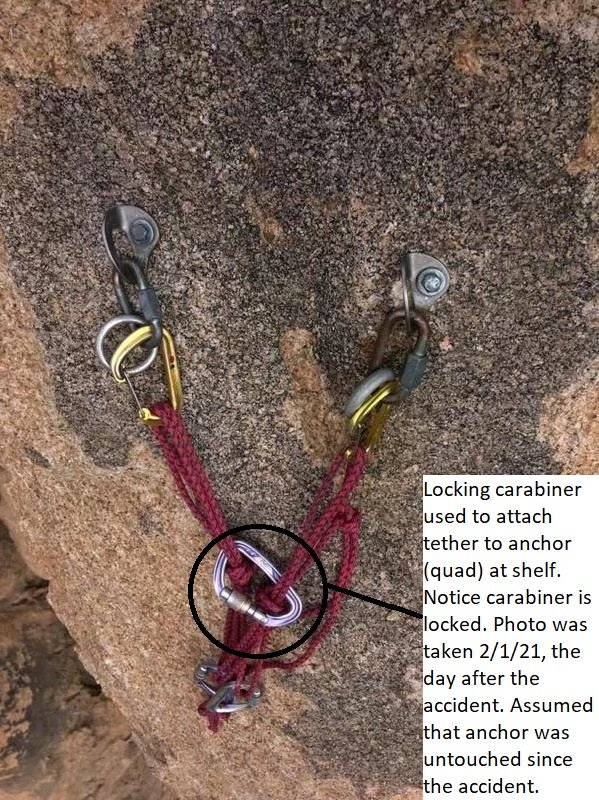

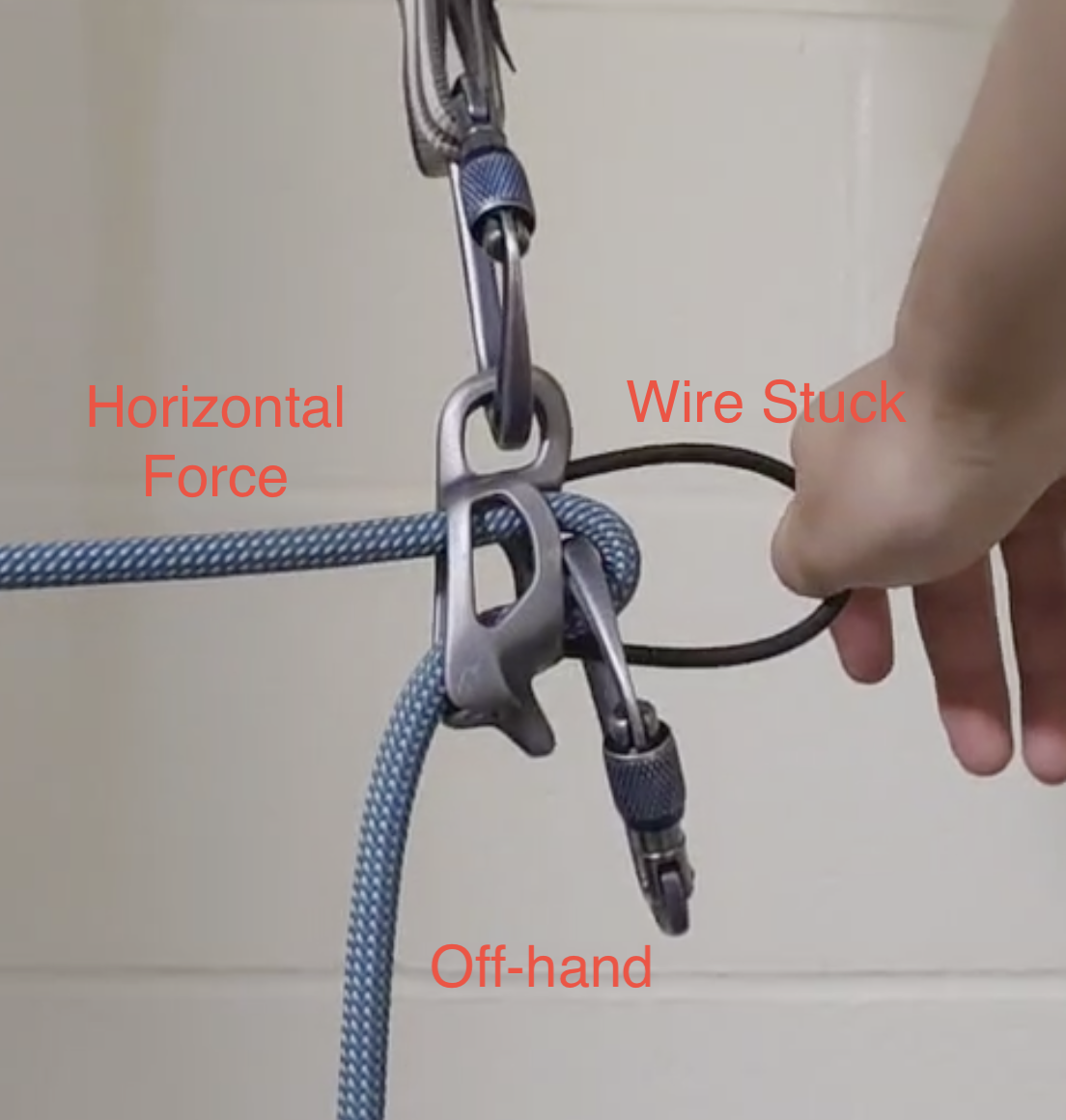

On January 8, Climber 1 (female, 25) got her knee stuck in a wide crack on the Regular Route (3 pitches, 5.7) on Queen Victoria Spire in Sedona. Climber 1 was following four friends on her first outdoor climb when she attempted an “alpine knee” while pulling onto a ledge on the second pitch.

An “alpine knee” is when you place that joint on top of a high hold and use it for progress, instead of a foot. Rather than helping her onto the ledge, Climber 1’s knee slipped into a four-inch-wide crack, where it wedged and became stuck. Others in her party tried pouring water over her knee in an attempt to free it but were unsuccessful.

At 5:15 p.m., the Coconino County Sheriff’s department was contacted to perform a rescue. By 8 p.m., the SAR team had arrived. It took over an hour to free the climber from the crack, and by then the climber was exhibiting signs of mild hypothermia (they had started climbing at 12:30 p.m.). The climbing party was airlifted off the spire. The stuck climber was not injured and refused treatment.

ANALYSIS

The climbers in this scenario did “everything right,” according to the SAR team. They tried to free their partner, and failing that, they initiated a rescue. Many relatively easy routes have awkward sections or styles of climbing that may seem above the technical grade when first encountered outdoors. Care should be taken when making a move where a slip or fall could result in injury or entrapment. It took about four hours to free this climber, and temperatures at the crag dropped to around 30°F. Consider worst-case scenarios when preparing for a climb, as unexpected events could result in prolonged exposure to the elements.

(Source: Dan Apodaca.)

Video Analysis

If getting your knee stuck in an offwidth is so common, what do we do if it happens? In the video analysis, ANAC editor Pete Takeda provides some tips on how to prepare for this kind of worst-case scenario when rock climbing.

Credits: Pete Takeda, Editor of Accidents in North American Climbing, and Hannah Provost, Content Director; Producer: Shane Johnson and Sierra McGivney @Sierra_McGivney; Videographer: Foster Denney @fosterdoodle_; Editor: Sierra McGivney @Sierra_McGivney; Location: Cob Rock, Boulder Canyon, CO

Similar Accidents—Accidents in North American Climbing

2022 | Leg Stuck in Crack

California, Joshua Tree National Park Left Horse Area2019 | Stranded—Knee Stuck in Wide Crack

Minnesota, Sandstone, Robinson Park2014 | Stranded—Knee Jammed in Crack

Wyoming, Vedauwoo, Easy Jam2009 | Stranded—Inability to Remove Anatomical Protection

California, Yosemite Valley, Bishops Terrace2006 | Stranded—Leg Stuck in Crack

British Columbia, Purcell Mountains Bugagoo Spire, Kain Route

Sign Up for AAC Emails