We sat down with the master of climbing mindset, Hazel Findlay. Hazel has made many significant free ascents of El Cap, and is one of the very few to climb the storied single pitch trad test piece, Magic Line. In this episode of the podcast, we talk with Hazel about her history with Yosemite, the projecting process for Magic Line, and of course, tips and tricks for building a strong mind. She shares some of her best insights about finding flow; a new concept that compliments flow, called clutch; first steps towards building a personal sending philosophy; and even a few practical exercises you can put into practice right now to start working on your headgame. And of course, how this all got applied during her own projecting process for Magic Line, because Pro’s struggle with headgame too!

2024 Annual Benefit Gala Awards

MEET THE AWARDEES

Discover their incredible stories, then join us for the 2024 Annual Benefit Gala to hear more!

The Climb of the Year Award

For pushing the limits of climbing, whether that is the grade or the most epic story—the redemption arc, the new frontier, or defying the odds. This award is determined by public voting.

The 2024 nominees include:

Round Trip Ticket (M7 AI5+ A0 2700M), Jannu (7710m), Matt Cornell, Jackson Marvell, and Alan Rousseau

B.I.G. (5.15d), Jakob Schubert

Aletheia (D16), Kevin Lindlau

Box Therapy (V16, contested), Katie Lamb.

The Community Changemaker Award

For the movers and shakers, the innovators, the loud voices and the doers. The people who, no matter the size of their platform, are making an outsized difference in shaping the future of our climbing community.

The 2024 nominees include:

Tommy Caldwell

Adaptive Climber's Festival

Marcus Garcia

The Robert Hicks Bates Award: Matt Cornell

For an Outstanding Accomplishment by a Young Climber

Matt Cornell grew up in Michigan, where he began climbing at the age of 13. Once he turned 18, he headed west to climb full-time, following the seasons from Bozeman to Yosemite, and then on to Patagonia and the Himalayas. In 2021, after steadily building his skills and experience, he and Jackson Marvell (Robert Hicks Bates Award recipient in 2020) established two new routes on Pyramid Peak in Alaska's Revelation Range, Techno Terror (AI6 M7+ R A0) and Smoke' Em If You Got 'Em (AI5+ A2+); Austin Schmitz and Jack Cramer joined the latter ascent. Cornell received the American Alpine Club's Cutting Edge Grant for this trip.

In late March 2023, with Marvell and Rousseau, the three climbed a new route on the east face of Mt. Dickey in Alaska's Ruth Gorge over three days, Aim For the Bushes (AI6 M6 X). Then, in early October, roping up with Marvell and Rousseau over seven days, they climbed a new route on the north face of Jannu, 7,710m, in alpine style. They called their line Round Trip Ticket (M7 AI5+ A0).

Angelo Heilprin Citation: Alison Osius

For Exemplary Service to the Club

"We chose [Alison] from a list of candidates we've carefully curated over the years. As many can attest, she's shown exemplary service to the Club by devoting countless hours in various recent and past roles, including as the Club's first woman president, from 1998 to 1999." -Selection Committee.

Alison Osius has been devoted to the Club for decades. She attends board meetings, annual dinners, panel discussions, and Club events. She's a trusted authority, a keeper of institutional knowledge, and vital to the community. Osisus is known for her engagement and mentoring of younger climbers and writers in their careers and her ability to relate to people from all walks of life who enjoy different climbing styles.

As the Club's first female president (1998-1999), Alison led the AAC’s first extended public outreach campaign and continued the effort into rule-making on fixed anchors in Wilderness. Her many years of elegant writing and superb editing for prominent publications have delighted climbing and outdoor audiences. She is a senior editor at Outside and a former editor at Climbing and Rock and Ice. Osius has written for CNN.com, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal.

Her strengths as a storyteller, communicator, and role model build on her many years of climbing experience, including her previous work as a climbing guide in the U.S. and U.K. and becoming a three-time national champion in sport climbing, X Games finalist, and top-10 World Cup finisher. Rooted in her love of climbing, her abiding curiosity and exploration of our world, and her empathetic and inclusive approach to others, Alison's exemplary service to the Club has dramatically strengthened the AAC.

Honorary Membership: Kitty Calhoun and Geoff Tabin

Honorary Membership is one of the highest awards the AAC offers. It is given to those individuals who have had a lasting and highly significant impact on the advancement of the climbing craft.

The Honorary Membership Committee has selected Kitty Calhoun and Geoff Tabin as our 2024 nominees. Both are well known and recognized for their amazing climbing achievements, exemplary service to their communities, and lifetimes of noteworthy activities which reflect well on climbing—Tabin in medical outreach to underserved peoples often in mountain regions and Calhoun in her leadership actively supporting the development of women in climbing during the last 30 years.

Kitty Calhoun is honored to receive this award and happy to share her most proud accomplishments. She received an MBA from the University of Vermont, where she found her passion for ice and alpine climbing. This led to a 40+ year career as a guide for the NC and CO Outward Bound Schools, American Alpine Institute, and Chicks Climbing and Skiing. Calhoun founded Exum Utah Mountain Guides and later became co-owner of Chicks Climbing and Skiing. She is also an ambassador for Patagonia, SCARPA, PMI ropes, POW, and Lion Energy. Additionally, Kitty has been a member of the American Alpine Club since she can remember, has served on the Board of Directors, was Chairperson of the Expeditions Committee, and has received the AAC's Pinnacle Award.

Calhoun's mountaineering achievements include a rare ascent of the Diamond Couloir on Mt Kenya, the first American female ascent of Dhaulagiri, three new Grade VI rock routes in Kyrgyzstan, and a new route on Middle Triple Peak in Alaska. She attributes her successes to applying the power of teamwork, which she learned through alpine climbing.

Geoffrey Tabin began climbing at Devil's Lake, Wisconsin. He went to college at Yale University, where he explored the rock and ice climbs of the Northeast from New York, New Hampshire, and Vermont, in addition to trips out West. He joined the American Alpine Club in 1977. He then went to Oxford University in England, where he and his climbing partner climbed the classic hard routes of the Alps. He received grants from the American Alpine Club and Oxford University to climb in Africa and Irian Jaya, Indonesia. They climbed the Ice Window route on Mt. Kenya and the first ascents of three long rock routes on the Mt. Kenya Massif, including the first free ascent of the Diamond Buttress on Mt. Kenya (V 5.11). In Indonesia, they climbed all five of the highest peaks in the Carstenz range, including the first ascent of the North Face of Puncak Jaya (Carstenz Pyramid). In 1983, Tabin was part of the American team that made the first ascent of the Kangshung East Face of Mt. Everest. In 1990, he became the 4th person to reach the top of all seven continents. Along the way, he also completed first ascents of rock or ice routes on all seven continents, including the first ascents of five 6,000-meter peaks. Tabin attended Harvard Medical School, trained as an ophthalmologist, and then worked as an eye surgeon in Nepal. He established the Himalayan Cataract Project, which is dedicated to overcoming needless blindness through education, training, and establishing a sustaining infrastructure. After returning to the United States, Tabin taught at both the University of Vermont and the University of Utah while spending three to four months per year working in Asia and Africa. He is currently the Fairweather Foundation Chair and Professor of ophthalmology and global medicine at Stanford University.

The H. Adams Carter Literary Award: James Edward Mills

For Excellence in Climbing Literature

James Edward Mills is a National Geographic Explorer and a contributor to National Geographic Magazine, a Fellow of the Banff Center Mountain & Wilderness Writing Program in Alberta, Canada, and a recipient of the Paul K. Petzoldt Award For Environmental Education. He has worked in the outdoor industry since 1989 as a guide, outfitter, independent sales representative, writer, and photographer. He is the author of the book The Adventure Gap: Changing the Face of the Outdoors and the co-writer/co-producer of the documentary film An American Ascent. Mills is a contributor to several outdoor-focused print and online publications such as National Geographic, Outside, Rock & Ice, Alpinist, SUP, Elevation Outdoors, Women's Adventure, the Clymb, Park Advocate, High Country News, Appalachia Journal, The Guardian, The New York Times, Sierra, and Land & People.

In recognition of his work sharing the important history and legacy of the Buffalo Soldiers and their efforts at the dawn of the National Park Service, James was named a Yosemite National Park Centennial Ambassador in 2016. Currently, Mills is a faculty assistant at the University of Wisconsin Nelson Institute For Environmental Studies and teaches a summer course for undergraduate students on diversity, equity, and inclusion in outdoor recreation and public land management called Outdoors For All. His climbing accomplishments include two ascents, one solo, of the mountaineers' route on California's Mount Whitney, sport climbing routes on the Gheralta Massif of Ethiopia, a team ascent of Mt. Baker, and a trek to Everest Base Camp.

The committee believes it's hard to overstate the importance of The Adventure Gap: Changing the Face of the Outdoors in shaping the discourse around justice and equity in mountaineering since it was published in 2014, which is why James Edward Mills absolutely deserves to be celebrated with the H. Adams Carter Literary Award for this year.

The Pinnacle Award: Steph Davis

For Outstanding Mountaineering and Climbing Achievements

Steph Davis is a rock climber, BASE jumper, and wingsuit flier. She began climbing as a freshman at the University of Maryland in 1991. After receiving a master's in Literature, she moved out to Moab, living in her grandmother's Oldsmobile. Some of her notable ascents are the First Female Ascent of Freerider, the First Female Ascent of the Salathe Wall, free solo of the Pervertical Sanctuary on the Diamond of Longs Peak, and the first American woman to summit Fitzroy. Davis started skydiving and BASE jumping in 2008; human flight is her second passion. She is one of just a few people in the world, and the only woman, to combine free solo climbing with base jumping and wingsuit flight. She is the author of High Infatuation and Learning to Fly.

The David A. Sowles Memorial Award: Roger Schaeli, Matteo Della Bordella, Thomas Huber, and Roberto Treu

For Unselfish Devotion to Imperiled Climbers

The Cerro Torre Rescue

Patagonia is considered by the world’s best climbers to be one of the most difficult and dangerous climbing areas in the world. Climbers who attempt Cerro Torre, Fitz Roy, and other notable climbs understand an accident here requires self-rescue, as an organized rescue is unlikely or uncertain at best. Two teams established two new routes on Cerro Torre on January 27, 2022. The teams had climbed the last 1,000 feet with each other, summiting together. The Italian team, Matteo Della Bordella, David Bacci, and Matteo De Zaicomo, decided to bivy up on the summit of Cerro Torre and descend the next morning while the other team, climbing guides Tomás Aguiló, 36 (Argentina), and Korra Pesce, 41 (Italy) decided to descend in the dark to mitigate the danger of rock and icefall.

As Aguiló and Pesce descended, on the morning of January 28, they were hit by an avalanche of ice and rock. Pesce was paralyzed, while Aguiló was seriously injured, but able to move. Aguilo continued to descend, eventually finding his satellite device and calling for help.

Unaware of Aguiló's satellite device message for help, someone had seen a headlamp's SOS signal high on the mountain and got together a group of ten to hike the two hours to the glacier's base and investigate. Some of the group continued on to the base of the east face, where they saw Aguiló slowly descending to a triangular snowfield about 1,000 feet of technical climbing above the glacier. A drone was used to pinpoint Aguiló's location, and a rescue operation was formed.

By 5 p.m. on Friday, Della Bordella's team had finished rappelling 30 pitches from their summit bivy and met up with the rescue party. Upon learning the news, Della Bordella, alongside Thomas Huber (Germany), Roger Schaeli (Switzerland), and Roberto Treu (Argentina), climbed the first seven pitches of the Maestri Route in three hours to reach Agulió. Around midnight, Treu and Huber descended with Aguiló, while Della Bordella and Schaeli waited for any sign of Pesce. A storm was approaching, and the two only had one rope between them. As the weather worsened and exhaustion set in, the two decided to descend for their own safety around 3 a.m. Unfortunately, Pesce perished. Rescuers carried Aguiló down to the bottom of the glacier, where he was helicoptered to a hospital.

The American Alpine Club is honored to recognize Matteo Della Bordella, Roger Schaeli, Thomas Huber, and Roberto Treu with the David A. Sowles Memorial Award for their voluntary actions to rescue Tomy Aguiló and Korra Pesce on Cerro Torre. The David A. Sowles Memorial Award is the American Alpine Club’s highest award for valor, bestowed at irregular intervals on climbers who have "distinguished themselves, with unselfish devotion at personal risk or sacrifice of a major objective, in going to the assistance of fellow climbers imperiled in the mountains.” The recipients’ voluntary actions to rescue Aguiló and Pesce at great personal risk is the embodiment of why this award was created.

About the Rescuers

As soon as Roger Schaeli began walking, the mountains became his fate. For Roger, climbing is passion, a sentiment, a strong emotional confrontation with the mountain, life, and himself. Schaeli is an IFMGA(UIAGM/IVBV) Mountain guide and Swiss Alpinist. Schaeli has many notable ascents all over the world, including more than 56 ascents on the North Face of the Eiger, the first ascent of Odyssee (5.14 1,400m), and the linkup of the six most prominent North Faces of the Alps (Eiger, Matterhorn, Grandes Jorasses, Grosse Zinne, Piz Badile, and Dru) in a non-stop, unsupported trek over 45 days.

Matteo Della Bordella began climbing at 12 years old, thanks to his dad. In 2006, he joined the group of Ragni di Lecco and had the opportunity to grow both as a mountaineer and a person. He likes to climb technically difficult big walls in the most remote places on earth. Bordella's proudest achievements as an alpinist are the first ascent of the route Brothers in Arms on Cerro Torre's east and north face, the first ascent of the west face of Bhagirathi IV (6192 m) in the Indian Himalaya, the "by fair means" expedition to Greenland which involved 200 km of kayaks and the first ascent of Shark Tooth north face, the first ascent of Torre Egger West face in Patagonia, summiting the Cerro Torre three times, and Cerro Fitz Roy four times.

Thomas Huber is a German climber and mountaineer. Huber is known for his speed records and first ascents. Of his most notable climbs are the FA of the direct north pillar of the Shivling (6543m) with Iwan Wolf, which won them the Piolet d'Or, and the first ascent of El Niño and the first free ascent of Zodiac on El Capitan in Yosemite.

Roberto Treu "Indio" is originally from the province of San Juan, where he found his passion for the mountains. He is an IFMGA Mountain Guide at Patagonia Ascent and the director of the technical committee of the AAGM (Asociación Argentina de Guías de Montaña). Some of his most important achievements have been the Cerro Standhardt, Herron, Egger traverse, and the Directa Huarpe, a new route on the West Face of Cerro Torre. In addition to these climbs, Treu has climbed Cerro Torre and Fitz Roy numerous times.

The President's Award: Steven Swenson

For Extraordinary Accomplishments in the Climbing World

Steve Swenson grew up in Seattle and started climbing in the nearby Cascade Mountains at age14. He graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in Civil Engineering. He has been climbing for over a half-century with over twenty expeditions to South Asia, including ascents of K2 and Everest without supplemental oxygen. He was part of a team that won the 2012 Piolet d'Or award for the first ascent of Saser Kangri II (7518 meters), and a team that won the 2020 Piolet d'Or for the first ascent of Link Sar (7041m). He is married with two sons. He is retired after a 35-year consulting engineering career in project management, design, policy-making, finance, and communications consulting related to water and wastewater infrastructure projects. Since his retirement, he has served on several nonprofit boards and has expertise in governance, fundraising, and strategic planning. His book titled Karakoram: Climbing Through the Kashmir Conflict was published by Mountaineers Books in 2017.

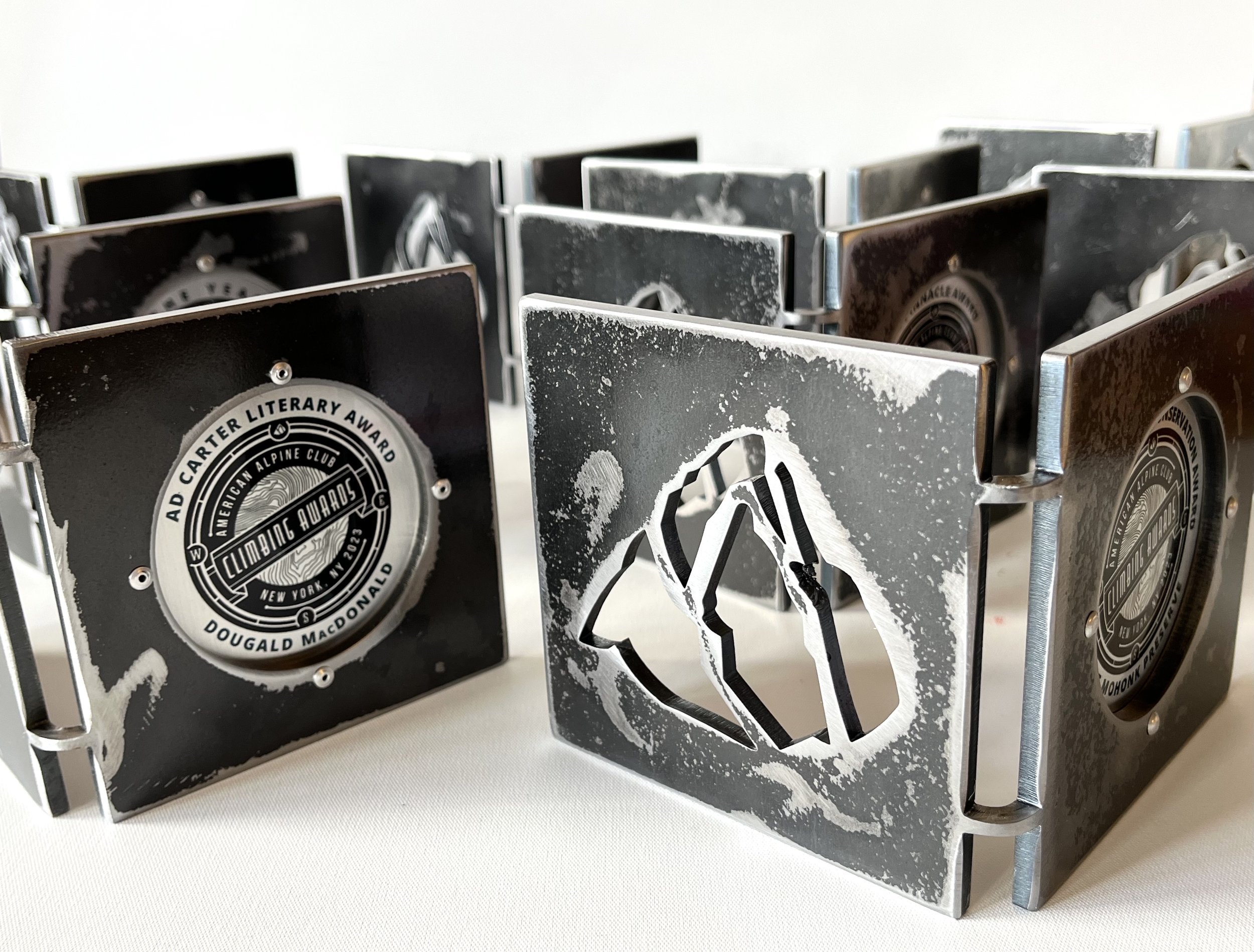

American Alpine Club award winners will be honored with bespoke, sustainable, custom-made awards by metal artist Lisa Issenberg. Lisa is the owner and founder of the Ridgway, Colorado studio, Kiitellä, named after a Finnish word meaning to "thank, applaud, or praise." Lisa has been providing custom awards for the American Alpine Club since 2013. Kiitellä's process includes a mix of both handcraft and industrial techniques. To learn more, visit kiitella.com

To hear more from these awardees, join us for the 2024 Annual Benefit Gala in Los Angeles, CA, on April 27, 2024.

GAME DAY: Hueco Rock Rodeo

It’s about to be game on for the 28th annual Hueco Rock Rodeo, and so we had our own Game Day panel to talk shop about strategies for the competition, the major players to look out for, and how the condies are shaping up. We had Nina Williams and Jon Glassberg on the pod to chat podium predictions, climbing rivalries, whose injured, and whose coming in with momentum, and whether Daniel Woods is really going to win the Hueco Rock Rodeo, AGAIN. Dive in to get all the beta on the top competitors, funny stories from past competitions, performance tips, competitive vibes, trash talk, and more.

Show Notes

The Prescription—February

The ice and mixed season is in full swing. While offering a dazzling range of sights, sounds, and textures, winter climbing arguably presents the highest risk to life and limb of any crag-oriented climbing genre. Ice is an ever-changing medium. The clothing and tools required deprive climbers of the accustomed “feel” for the climbing medium—so critical to fair-weather rock climbing.

This month we have two accidents from 2023. Both involved collapsing ice formations. One had an injury-free ending. The other ended in tragedy.

Code Red (WI 5) in Hyalite Canyon, before and after a dramatic collapse in January 2023. The two climbers involved in this accident fortunately emerged unharmed. Caption: Photo: Lauren Olivia Smith/Climbing magazine

Fall on Ice | Collapsed Pillar

Hyalite Canyon, Montana

On January 27, 2023, Lauren Olivia Smith and Bailey Lasko, both of Bozeman, Montana, were climbing Code Red (WI 5) in nearby Hyalite Canyon. This single-pitch ice pillar has a longer approach than other popular venues in the canyon. The approach, combined with the avalanche hazard, made for a more serious outing.

Smith was leading. As she reported to Climbing magazine, “(From the approach gully)…the pillar looked funky and off-kilter, in a shape I’d never seen before…. I remember thinking it doesn’t look quite right, but the part that was leaning seemed quite big, and we had a big freeze-thaw [cycle], so I figured it was well-attached.”

From a closer vantage, Smith confirmed that Code Red appeared well-attached to the rock and “gave its stability no further thought.” At 15 feet up, Smith heard a cracking noise from above. The bottom half of the pillar then collapsed, toppling “like a falling tree.” Smith said, “I remember seeing a chunk of ice fall past me with my tool still in it.”

The point of detachment was 35 feet above Smith. With no intermediate protection, she—and the unanchored Lasko—"rocketed down the 30-degree approach slope.” Smith had been climbing on the lower-angled (left) side of the formation, and the inclined column fell away from her, so she avoided being crushed. The pair slid alongside the pillar before self-arresting after 100 feet, and they emerged unharmed.

ANALYSIS

Smith did well to assess temperature patterns in the days prior to the outing. She also chose a line that was well-bonded to the top of the cliff. While Smith was surprised at the collapse, it’s worth noting that the unusual crooked profile indicated the pillar had previously cracked and toppled partway before refreezing at a Pisa-like tilt. Inclined columns are subject to axial compression, shear forces, and in this case, buckling. Smith says she now completes a full 360-degree inspection of any free-standing ice pillar before climbing.

(Sources: Climbing magazine, The Editors.)

Fall on Ice | Collapsed Pillar

Right Fork of Indian Canyon, Duchesne, Utah

On April 2, 2023, Meg O’Neill (40), a member of a party of three climbers, was killed when struck by a collapsing ice column on Raven Falls (WI4), near Duchesne in northeast Utah. According to the Duchesne County Sheriff’s Office, O’Neill, who was standing nearby, saved the belayer’s life by pushing her out of the fall zone. The leader was seriously injured.

Sean McLane (34) was on lead near the top of the second pitch when the accident occurred. He was belayed by Anne Nikolov (21), while O’Neill was spectating.

Sean McLane climbing Raven Falls (WI 4) on an earlier ascent. This two-pitch climb near Duchesne, Utah was the scene of a fatal accident in April 2023. McLane wrote, “On the day of the accident, it looked about the same (as in this photo). Photo: Sean McLane

McLane wrote to ANAC, “It had been warm for a couple days, and this was to be my last climb of the season. We were a group of three. Meg was experienced and a regular climbing partner of mine. Anne was new and had climbed a couple times with Meg.”

McLane led the first pitch and brought the other two up. The base of pitch 2 was a broad snow ledge about 100 feet above the top of the first pitch.

“The second pitch was an ice column that formed at the lip of a cave. The column was 40 feet high and 15 feet in diameter. I saw no signs of instability. I didn’t see or hear any significant running water. There was little to no cone at the bottom, although a 15-foot radius of ice was present at the base. I stomped on it to test for anything being undercut, but it felt solid, likely because it was a couple feet thick and my weight wasn't enough to stress it.”

“I led out the back of the ice and corkscrewed around to the side. Anne (Nikolov) was belaying and Meg (O’Neill) was walking around, taking pictures. As I [was nearly] top[ping] out, there was a significant density change in the ice. It went from wet, one-swing sticks, to dense… dinner-plating [hits]."

McLane climbed above the point where the ice was attached to the rock. As he swung an ice tool into an already dinner-plated placement, the pillar fractured, breaking two or three feet below the point of the pick’s impact.

According to McLane, the collapse took “my other tool and both my feet with it. Meg was in the cave behind the pillar, and Anne was to the side. Most of the column went downhill, but falling ice buried Meg.”

Climbing magazine wrote that O’Neill “noticed the ice fracture, and… may have heard it cracking just before the formation broke.” She then pushed Nikolov aside, and as also reported in Climbing magazine, “Her quick thinking undoubtedly saved Anne’s life.”

McLane recalls, “I had placed screws in the pillar and was pulled off by the rope. The main column fell down the slope away from me, and I came straight down. "I hit the ground... land[ing] on my back [atop] a large chunk of ice. [This] broke my spine at L2... That was my only injury besides scrapes and bruises. I put myself in recovery position as Anne tried to get to Meg.”

The closest cell signal was driving distance away. McLane showed Nikolov how to fix a rappel line and then gave her his phone along with directions to access the car keys. Nikolov safely descended, drove to town and contacted SAR and local climbers. About six hours after the accident, some Salt Lake climbing friends arrived. McLane was long-lined by helicopter to the road. He was then loaded into another helicopter and flown to a hospital in Salt Lake City.

*Editor’s Note: This is an example of a hidden ice climbing hazard called a False Pillar. To learn more, click the link below.

ANALYSIS

Alpinism and ice climbing are perhaps the most dangerous of climbing games. As mentioned above, frozen water is a fickle, ever-changing medium. And, as demonstrated in these two accidents, the hazards are often invisible. In no small way, luck was a determinant factor in the different outcome of these two accidents.

On Raven Falls, McLane—a very experienced climber who had safely climbed the route twice previously—visually assessed the ice and stomp-tested the base to ensure the column was attached. He wrote to ANAC that, “In retrospect, to fail as it did, the pillar must have been melted out from underneath.” The solid-looking column was basically a free-hanging, bus-sized chunk of ice.

McLane has physically recovered; it took about six months to get back to normal climbing.

McLane notes:

Running water underneath an ice formation can render a solid and fully attached flow free-hanging and unstable. Figuring out if ice is undercut can be hard to impossible to do, without seeing the running water or the gap between the bottom of the pillar and the base. Several days of warmer temperatures can create this dangerous situation.

Large variations in ice quality and density (on the route) may signal stability issues.

(When belaying or spectating) Position yourself farther away than you might think in order to stay out of the way of falling ice. A cave is not necessarily protected if the ice collapses.

Carry an extra layer (pack it with you on your harness or in your pack). Since it was a warm day, I left my puffy at the base, a pitch below. I got very cold lying on ice and not moving for many hours.

If you might need something on a multi-pitch route, don’t leave it at the base. A satellite communicator and warm layers with me on pitch two would have made a bad situation more manageable.

(Source: Sean McLane, Climbing magazine, and The Editors.)

To Climb or Not to Climb?

More people than ever are ice climbing. At the same time, climate change is dramatically affecting geologic stability in the mountains. Changes include rock fall, glacial recession, and waterfall ice collapse. The intersection of ice climbing popularity and effects of climate change can cause accidents.

This flowchart was developed by Derek DeBruin. It was first published in the 2023 ANAC. This tool can assist in managing hazards by helping determine the stability of the ice, the effectiveness of ice screw protection, and the quality of ice tool placement. Downloadable PDF and image are available through the link below.

The Prescription is the monthly newsletter of Accidents in North American Climbing. The Prescription brings you monthly unpublished accident reports, tech tips, links to new online educational resources, and much more—all aimed at helping you become a safer climber.

Sign Up for AAC Emails

A Little Extra Spice: Stories from the World of Competition Ice Climbing

Catalina Shirley Climbing in Ouray. PC: AAC Member Nicholas Moline

By: Sierra McGivney

Ice cascades into the Uncompahgre Gorge, creating an ice climber's paradise. With more than 150 manmade ice and mixed climbs across almost 2 miles of terrain, Ouray Ice Park is an ice climbing playground, and the Ouray Ice Festival is the ultimate celebration of that. This year, the ice fest kicked off on Thursday, January 18, with a Barbie pool party and lasted through the weekend. Pros and ice climbing connoisseurs taught clinics, pushed grades, and had fun, but Ouray is also often the first and only time rock climbers try ice climbing. All types of clinics are offered, demo gear is included in an all-access pass, and volunteers belay at the walk-up wall, making the Ouray Ice Festival an accessible entrance to the sport.

That's precisely how Ian Umstead, now a USA Ice Climbing Team athlete, tried ice climbing for the first time two years ago. He originally wasn't sold on ice climbing. He had fun but thought it was sketchy. But something clicked when a friend invited him to go dry tool at a local crag in March 2023.

"It's like sport climbing with a little extra spice," said Umstead.

Ian Umstead Climbing in Korea. PC: Provided by the UIAA

Umstead is primarily a sport climber, so he had strength built up from sport climbing that translated into dry tooling. A couple of athletes on the Ice Team encouraged him to try out for the team even though he had only been dry tooling for three months. Umstead was surprised they suggested it but thought: If I'm going to do this, I'm going to do it right. So, he put off his sport project and trained on tools for eight weeks. Then, he went to tryouts and made the team. He was stoked. Umstead returned to training for his sport project, and after five weeks, he sent his first 5.14. Umstead has a semi-professional bike racing background, so he eats and breathes training and competing.

"I'm a projecter's projecter," said Umstead.

He picks challenging projects, trains, and tries hard. Drytooling fulfills that, adding an element of goofiness. The movements feel silly and fun and keep Umstead engaged.

Umstead is one of many athletes who started in Ouray. Connor Bailey first tried ice climbing in Ouray at eight years old. He remembers his crampons falling off because his boots were too small, but he liked it. Scratch Pad, a dry tooling gym in Salt Lake City, contacted his climbing team and asked if anyone wanted to try out for the youth ice climbing team. He and one of his friends, Landors Gaydosh, decided to check it out.

"I thought it was going to be just ice climbing," said Bailey. "I was pretty excited. I went in there and saw all the different holds and was like—huh?"

Left to right USA Ice Team Athlete’s Connor Bailey, Tyler Kempney, Mathius Olsen. PC: Provided by Stephanie Olsen.

The holds and movements were similar enough to rock climbing that Bailey found success. Initially, the comps had no age requirements, so he could join the team and compete. Unfortunately, this past year, the youth age requirements changed, and Bailey, who is 12, falls below the youth age requirements. Thankfully, he could still compete in Ouray.

Bailey sometimes questions why he chose this sport, especially when it's cold, but once he begins swinging his tools and warms up, he loves each movement.

From the snow-covered bridge leading into the vendor village, the giant competition wall rises up from the gorge. Starting from the bottom of the gorge, competitiors climb on rock and ice, until they reach the artificial wall, where they begin placing their tools on holds made of various materials. The Ouray Ice Festival is a crucial competition for the USA Ice Climbing athletes as part of the UIAA Continental Cup Series. On the Saturday of the festival, commentators and spectators gather, and above the din of music playing, people cheer on the competitors in the finals.

Catalina Shirley began her climbing career young—like most of us do—climbing trees and doorways, scaring the sh*t out of our parents. When Shirley began venturing to the roof of her parents' house, her mom drew the line and signed her up for summer camp. Shortly after, her family moved to Durango, Colorado, where she joined Marcus Garcia's team. Garcia was working on building out the USA Ice Climbing Youth team. Shirley began training and went on to compete in France the following year when she was fourteen.

"I love the kinds of moves that you can do in ice climbing that you can't quite get in rock climbing—like the crazy floating underclings and gastons and, of course, figure fours and anything on swinging features," said Shirley.

Shirley likes the thought required for every move and the freedom of movement in dry tooling. Climbers can put their feet anywhere, regardless of body size or strength. But in Ouray, the competition wall reminds Shirley of a puzzle, with only one right way to solve it. Part of that puzzle in the Ouray Finals was a dyno. Shirley set up for it, looking out at the crowd. Then she jumped and closed her eyes, landing slightly above the hold but sticking it. When she opened her eyes, everyone screamed, infusing her with energy. With one minute left on the clock, she went as fast as she could, letting the crowd's energy flow into her. She placed first in the women's lead competition.

"I feel like I perform the best when I'm under a little bit of pressure," said Shirley.

Catalina Shirley Climbing. PC: AAC Member Nicholas Moline

The weekend before, January 12 through 14, Shirley placed second in both lead and speed in Cheongsong, Korea. She is the first American to make the lead podium—man or woman. The competition setting is her style: long figure fours, roof climbing, and endurance-based; climbing fast is one of her strong suits. She got to the top of both qualifier routes. She was one of three women to do so, next to Marianna Van Der Steen and Woonseon Shin, both of whom Shirley had been watching since she was a kid.

But in the Cheongsong finals, Shirley had fallen three moves from the top because she missed the dyno. Sticking the dyno in Ouray means that much more. She credits her team as a big reason why she made the podium. They provided support for her all weekend, from food to encouragement. Her team had her back.

"It really felt like the whole team's medal," said Shirley.

Shirley believes there are four main challenges to competitive ice climbing: strength, problem-solving, fear of falling, and fear of failing. It's what keeps bringing her back. In "regular" life, rarely are all those elements compounded.

"Overcoming all of that is the best feeling in the world," said Shirley.

Sam Serra Climbing. PC: AAC Member Nicholas Moline

Each person on the USA Ice Climbing Team has their own story.

Sam Serra attended an intro to ice climbing class hosted by the Ice Coop in August 2021. Tyler Kempney was teaching it and asked if anyone wanted to try dry tooling. Serra had a blast.

"I went to get into ice climbing, but I feel like I really got into dry tooling," said Serra.

He didn't get on ice until two months later. As Serra spent more time at the Ice Coop, he got dragged into competing. His first competition was in Michigan, only a couple of months after he began climbing. It wasn't his strongest competition, but he found climbers he wanted to surround himself with. The community kept him around until he learned to like dry tooling competitions. Serra grew to love the movement and style of competition dry tooling. The unique way of using your ice tools pushes the climber to be creative in a way that differs from traditional ice climbing.

Sam Serra being lowered. PC: AAC Member Nicholas Moline

"When It comes to dry tooling and really competition style dry tooling–it just opens the door to so many new movement patterns that they don't even exist outside–they almost can't exist outside," said Serra.

Phoebe Gabrielle Tourtellotte's story looks a little different. Tourtellotte had to drop out of speed climbing due to a joint condition in the fall of 2021. She felt aimless. At the time, she lived across from the Ice Coop in Boulder. Her boyfriend encouraged her to try that dry tooling thing. Despite inner doubts about how she would look or perform, she went.

In the first couple of months that she was learning to dry tool, she had to confront why she was still climbing at all after speed climbing hadn't worked out. Then it hit her: here was an opportunity to start over.

"It's so cool getting to learn all new stuff," said Tourtellotte, "There are so many tiny nuances I never would have expected to learn about in this sport."

She had gone from one of the fastest disciplines to one of the slowest and methodical. Coming from a speed-climbing background, Tourtellotte moves more dynamically. At the Ice Coop, she gets beta and technique spray-downs from everyone in the gym. Her teammates are open to mentoring each other, even if they're competitors.

The USA Ice Climbing Team in Cheongsong, Korea. Provided by the UIAA

The small community of competition ice climbing supports and uplifts one another. It brings together people of all ages and backgrounds, connected through their niche passion for ice climbing and dry tooling. The team will continue to swing tools, compete, and celebrate their love of climbing through silly and unique movements.

Ouray Ice Fest Results

Catalina Shirley placed first in the Women's lead final, with Corey Buhay in Third. Tyler Kempney placed first in the men's lead final, with Sam Serra placing second. They both topped the finals route. The Ouray Ice Festival competition is a special place for the team, for everyone to gather and celebrate. The USA Ice Climbing team will end their season at the World Championships In Edmonton on February 16 through 18. Tune in to the UIAA YouTube channel to livestream the event and support the USA Ice Climbing Team.

UIAA Ice Climbing Continental Open - Ouray, USA: Top Three

The Women's Lead Final

1 Shirley, Catalina USA 1 [1] 1 [36.100]

2 Louzecka, Aneta CZE 4 [12.0] 2 [31.000]

3 Buhay, Corey USA 3 [9.0] 3 [28.100]

The Men's Lead Final

1 Kempney, Tyler USA 1 [1] 1 [TOP (0:00)]

2 Serra, Samuel USA 2 [4] 2 [TOP (0:00)]

3 Howe, Tyler CAN 3 [15] 3 [33.000]

The USA Ice Climbing Team is Supported by

CLIMB: Kyra Condie on Winning Hueco, Fear of Falling, and Trying Harder

In this episode, we sit down with Mountain Hardwear athlete and Olympian Kyra Condie. Kyra has so much psyche and energy, and we had a wide ranging conversation, covering her past, present, and future climbing exploits. We start off with her experience winning the Hueco Rock Rodeo in 2017, her advice for competitors this year, and how her spinal fusion pushes her to have a creative mind and find her own beta. She also gave some excellent insight into the way comp climbers think, the key training focuses every climber should have, and how MORE climbers should get on routes and problems that are way too hard for them. Kyra is really open about dealing with fear of falling and fear of the unknown, and we unpack that and more, diving into relatable topics for most climbers. Finally, we cover her Olympic hopes for Paris 2024. Whether it's strategies for competing in Hueco, training tips, or mantras for good mental game, Kyra’s wisdom is worth the listen!

Fix CRUS: Help Protect Public Access to Recreation in Colorado!

Mining remains on Mount Sherman. Photo by Katie Sauter.

Policy Alert: Take Action!

As climbers, many of us are familiar with the often delicate and fragile access to climbing on private land. In Colorado, we now have the opportunity to pass legislation to ensure that our access to our beloved climbing areas is no longer so tenuous.

The crux of the matter is liability. The current Colorado Recreational Use Statute (CRUS) has private landowners concerned about the liability they take on when they allow the public to access their lands for recreation. The result has been a drastic number of closures or uncertainty for some of Colorado's most iconic recreational areas—including 14ers, attending the Leadville 100, and even climbing in Ouray Ice Park.

The AAC is part of the Fix CRUS Coalition, and we have worked alongside our partners as they crafted SB-58, a landmark bill that will fix the Colorado Recreational Use Statute (CRUS), ensure the balance of landowner rights, and protect public access to our state's natural wonders that are on private land.

Now, we need your voice to turn this work into a reality. This impacts more than just Colorado climbers, but our entire outdoor family that utilizes Colorado lands.

What SB-58 Does

This bill takes a carefully balanced approach to help limit landowner liability exposure while ensuring visitors are aware of non-obvious or man-made hidden hazards. SB-58 would do the following:

Protect landowners who put a warning sign up with pre-approved language at the main access point from lawsuits related to most natural, agricultural, and mining-related hazards.

Clarify that visitors must use a designated access point, stay on trails and within approved areas or they will be classified a trespasser for purposes of liability (not criminality).

Update which recreational activities are protected by CRUS, to include rock climbing, ice climbing, trail running, backcountry skiing, rafting, and kayaking, etc.

Your Role: Advocate for Colorado's Outdoors

Your voice is crucial. We urge you to contact your Colorado State Senator and Representative and express your support for SB-58 asking them to support and cosponsor the bill.

SB 58 is a bipartisan bill sponsored by Senators Mark Baisley and Dylan Roberts, and Representatives Shannon Bird and Brianna Titone. This bill has passed out of committee with unanimous consent, and we just need voices from Colorado outdoors enthusiasts like you to push it over the edge and make it a reality!

Whose Risk Is It?

Interested in learning how liability concerns impact recreation across the country? Do a deep dive into recreation, private land, and liability with our article “Whose Risk Is It?”

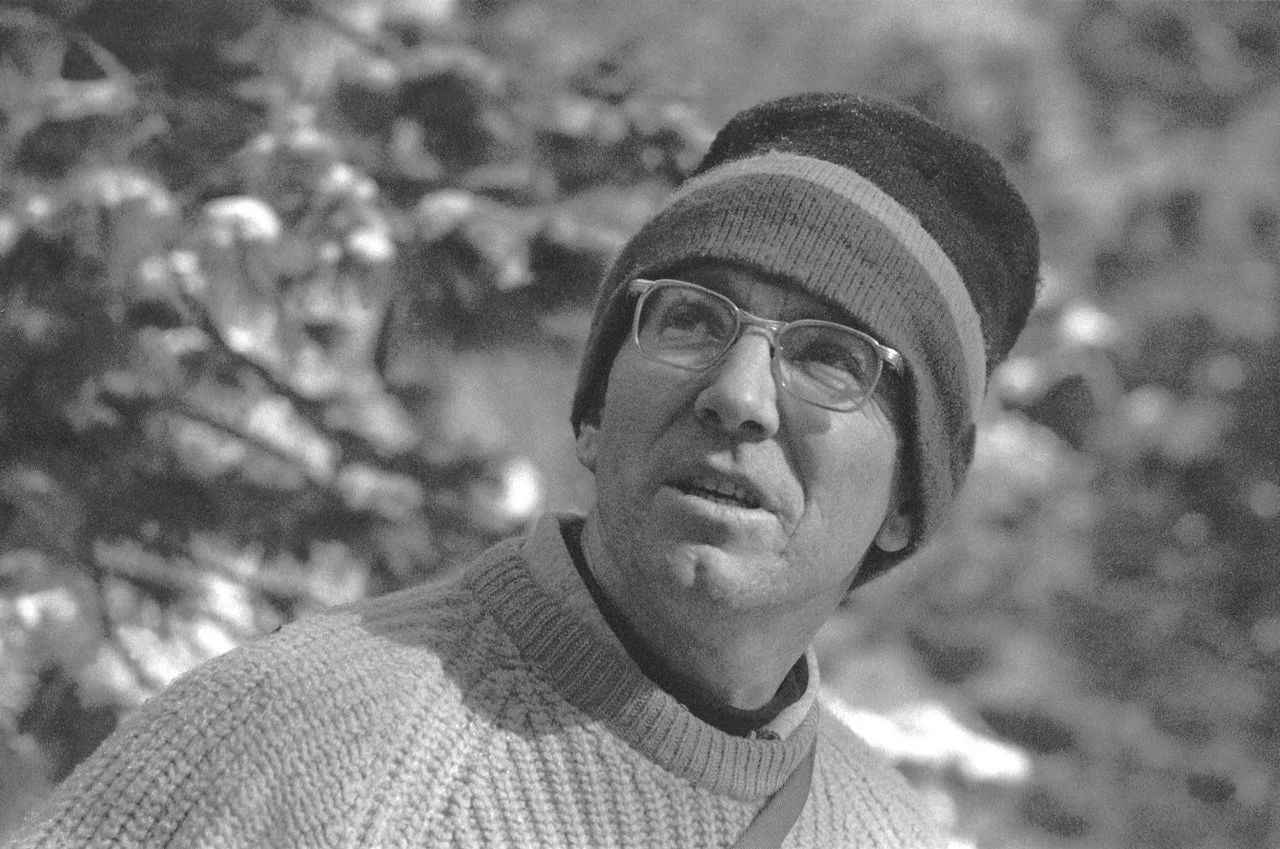

Legacy Series: Tom Frost

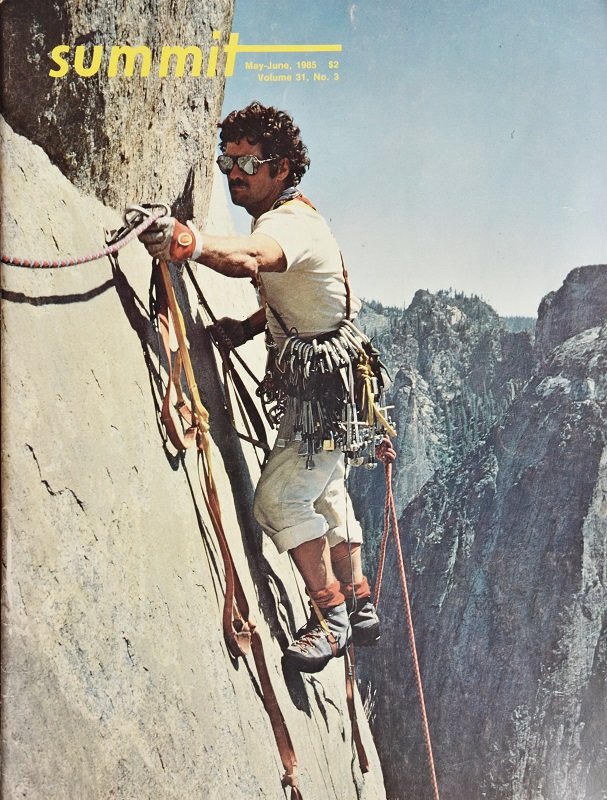

Tom Frost bivvying on El Cap. Photo by Royal Robbins, Courtesy of NACHA.

Tom Frost was one of the leading climbers of his generation, making important first ascents on El Cap, like the North America Wall and Salathé Wall. He was also a world-class alpinist and one of the main photographers who crafted a visual record of the Golden Age of Yosemite climbing, capturing the emotional imagery that would define a generation of climbers. Frost was at the forefront of defining clean climbing, often known for his enterprising and bold free climbing to avoid unnecessary bolting. He also engineered key climbing tools that we often take for granted today. In this interview with Tom Frost, we cover how he fell in with Royal Robbins, Chuck Pratt, Yvon Chouinard, and others; stories from his historic climbs; and how much he loved bivvying on the big walls of El Cap. Dive in to hear all this and more from this legend of climbing!

About the Legacy Series

A passion-project of AAC Past President Jim McCarthy and Tom Hornbein—themselves mountaineering legends by any standard—the American Alpine Club’s Legacy Series pays tribute to the visionary climbers who made the sport what it is today and stands as a commitment to securing their legacies.

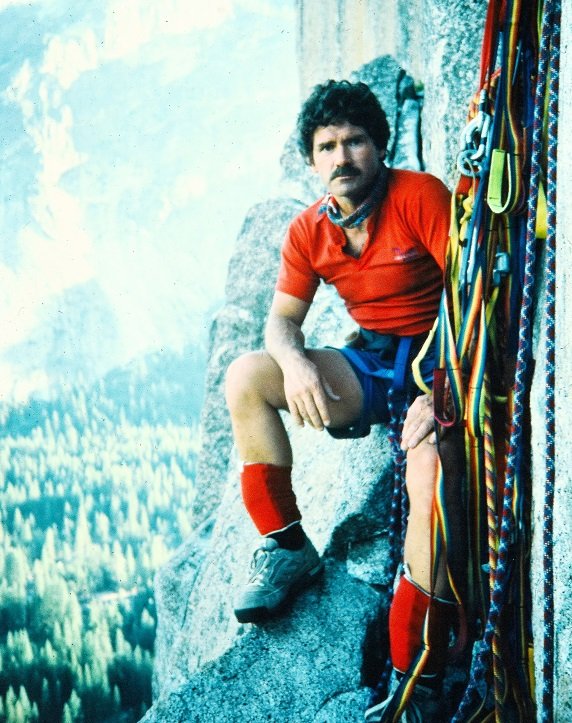

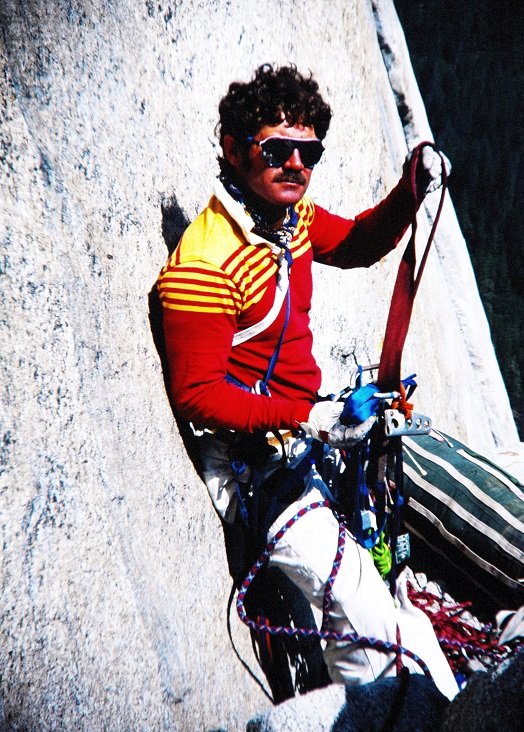

Legacy Series: George Lowe, World Class Climber

George Lowe on Mt. Foraker.

Few Americans have had a climbing career anything like George Lowe’s. And we’re not the only ones who think so: The Piolets d’Or selected Lowe for their 2023 Lifetime Achievement Award. From first winter ascents of the Tetons’ highest peaks in the 1960s, Lowe moved on to cutting-edge climbs in Canada and Alaska in the 1970s, including the north faces of Mt. Alberta and North Twin in the Rockies and the Infinite Spur of Mt. Foraker in the Alaska Range. In the early ’80s, he was instrumental in the first ascent of the extremely difficult Kangshung Face of Everest. At age 79, George is still at it—climbing and skiing at a high level—and in this film he shares his thoughts about his long and illustrious climbing career and the humility and companionship it takes to survive and excel in the mountains.

A passion-project of AAC Past President Jim McCarthy and Tom Hornbein—themselves mountaineering legends by any standard—the American Alpine Club’s Legacy Series pays tribute to the visionary climbers who made the sport what it is today and stands as a commitment to securing their legacies.

The AAC's Official Stance on the Proposed Fixed Anchor Guidance from the NPS and USFS

Photo by Sterling Boin.

Thanks to the diligent and extensive research and work by our policy director, Byron Harvison, the AAC has submitted the following public comments to the National Park Service (NPS) and United States Forest Service (USFS) respectively, about their proposed fixed anchor guidance in Wilderness Areas, on January 30th, 2024. Read the full statements by clicking each button.

An Excerpt:

“The AAC would like the National Park Service (NPS) and United States Forest Service (USFS) to adopt guidance which affirms that fixed anchors are not installations prohibited by the Wilderness Act and allow agency land managers to administer their areas in a similar manner with what had been established under NPS Director’s Order #41. In lieu of publishing such guidance, the AAC would ask that the NPS and USFS convenes a committee pursuant to the negotiated rulemaking process, or similar collaborative process, in order to address the issue of fixed anchors in Wilderness and implement guidelines following a committee report. The AAC reiterates that the MRA process is not only a technically incorrect tool for the evaluation of fixed anchors, but cannot be practically implemented due to agency underfunding and limited staffing, and such a process will inevitably lead to management by moratorium.

“The AAC will remain committed to instilling the ethos of maintaining wilderness character, utilizing the best low-impact climbing techniques and practices, and staunchly supporting appropriate recreation in Wilderness. The AAC is ready and willing to assist the NPS and USFS to deliver on their dual mandate of conserving Wilderness characteristics while also ensuring the benefit and enjoyment of the Wilderness for the broader public.”

Cathedrals of Wilderness

Three First Ascents from the Historic Roots of Wilderness Climbing

By Hannah Provost

Photo by Sterling Boin.

“ Wilderness areas shall be devoted to the public purposes of recreational, scenic, scientific, educational, conservation, and historical use.”

With much ado about whether the NPS and USFS will prohibit fixed anchors in Wilderness areas, the AAC thought we’d lean into one of our strengths—the immense amount of climbing history at our fingertips, thanks to nearly 100 years of documenting climbing through the American Alpine Journal and the AAC Library. Climbers have been utilizing and advocating for the responsible and thoughtful use of fixed anchors (including pitons, slings, and bolts) in what are now designated Wilderness areas since before the passing of the Wilderness Act in 1964. These stories from before Wilderness as we know it shows that climbers were thinking with careful judgment about the wilderness experience, and sparingly using fixed gear—if it was in fact crucial for the ascent or descent at all. Since then, recreation, including climbing, has been a major tenet of what the Wilderness Act aims to protect. The question is: how do fixed anchors fit into that commitment moving forward? And how do Wilderness climbing’s roots inform that future?

Check out the climbs below to get a sense of the roots of Wilderness climbing.

Check out this map, powered by onX, which features Mountain Project data in conjunction with Wilderness Area boundaries, to help visualize how climbing across the country is impacted by this discussion.

Take Action: Share Your Voice on the Proposed Wilderness Fixed Anchor Guidelines

From the 1963 American Alpine Journal. Photos by Tom Frost, courtesy of North American Climbing History Archive.

The Salathé Wall, Yosemite Valley

Designated Wilderness in 1984

3500 ft (1061 m), 35 pitches, VI 5.9 C2, Robbins-Pratt-Frost, 1961

One of the longest routes on El Cap—and full of infamous wide cracks and ledges to bivvy on, The Salathé Wall is one of the iconic climbs in the world. The route has you balancing up the Free Blast, and shimmying up chimneys until you’re climbing the impressively steep headwall that makes everyone gape at El Cap. If you’re a badass, you can free it at .13b. But in 1961 Royal Robbins, Chuck Pratt, and Tom Frost were just excited to get up the thing, placing minimal fixed gear.

From the 1963 American Alpine Journal. Photo by Tom Frost, courtesy of North American Climbing History Archive.

In Royal Robbins’ 1963 report for the American Alpine Journal (AAJ), in which he recounts the first ascent done in 1961 and the first continuous ascent done in 1962, Robbins grapples explicitly with the bolting choices he and his team made as first ascensionists. Reflecting on the first continuous ascent, Robbins writes: “Tom [Frost] skillfully led the difficult section of the blank area where we had placed thirteen bolts the previous year. The use of more bolts in this area had been originally avoided by some enterprising free climbing on two blank sections and some delicate and nerve-wracking piton work. It would take only a few bolts to turn this pitch, one of the most interesting on the route, into a ‘boring’ walk-up.” Robbins and his peers were invested in finding those moments of “enterprising free climbing,” where they had to get creative and grit their teeth. Throughout his career, Robbins would have a lot of ambivalence about bolts—Salathé is a perfect example of that careful balance.

Though not directly or explicitly linked with his stance on fixed gear, it’s notable that Royal’s account of the continuous ascent of Salathé is intertwined with soulful reminiscing about nature. Robbins and his team considered Yosemite a special kind of remote nature, well before El Cap got a Wilderness designation with a capital W. Robbins ended his Salathé report: ”We finished the climb in magnificent weather, surely the finest and most exhilaratingly beautiful Sierra day we had ever seen…All the high country was white with new snow and two or three inches had fallen along the rim of the Valley, on Half Dome, and on Clouds Rest. One could see for great distances and each peak was sharply etched against a dark blue sky. We were feeling spiritually very rich indeed as we hiked down through the grand Sierra forests to the Valley.” This experience of vastness—of feeling the smallness of humanity within the quietude of nature, and that such experiences are enriching to the soul—is at the heart of what the NPS and USFS are trying to preserve, and which climbers like Robbins and all those who have followed him up El Cap have deeply loved about these places.

Layton Kor on the first ascent of The Diagonal, 1963. Photo from Kor’s book, Beyond the Vertical, photographer unknown.

The Diagonal, Black Canyon of the Gunnison

Designated Wilderness in 1976

2000’ (606m), 8 pitches, V 5.9 A5, Kor-McCarthy-Bossier, 1963

The Diagonal is in some ways an odd route to include here, because although it was important at the time, and excellent tales have been told about this first ascent, this route is rarely climbed today. It has the distinction of half a star on Mountain Project, and is known for the boldness required—which is particularly important to note in an area that already favors the bold. But we’re including it here precisely because of the climb’s historic nature, and how the first ascensionists—the magic team of Layton Kor, Jim McCarthy, and Tex Bossier—have articulated their thoughts on fixed anchors.

As a historic climb, The Diagonal contains multitudes. Layton Kor, who was the driving force behind the first ascent, was certainly known to be a singular kind of person. There was no one quite like him. In Climb!, his contemporaries describe this towering figure in awed terms: “Of his more forceful characteristics, those who knew Kor well during his climbing years say that he frequently exhibited the qualities of a man possessed. A driving inner tension gnawed at him. His way of escaping from this sensation was to be active in a way which totally occupied his mind and body. His climbs, pushed to the limit of the possible, served this function well.” When Kor legendarily quipped, staring up at the crux pitch on The Diagonal, that he wasn’t a married man, and perhaps he should take Jim McCarthy’s lead for that reason, behind the glint in his eye was that tension and drive. Kor did take the lead on the “horror pitch,” taking six and a half hours to complete it—and it’s still noted as one of Kor’s hardest leads in his career. After all, the team was trying for glory—attempting to find Colorado’s first grade VI, though it would turn out to be another grade V. It remains an iconic moment in climbing’s rich history of contemplating and pushing past our agreed upon limits.

Bossier indicated, in Kor’s book Beyond the Vertical, that the boldness that would come to characterize the climb was due in part to an intentional philosophical stance that the team made about the restrained use of fixed gear. Bossier writes: “The two major ethical dilemmas of the day were expansion bolts, and siege vs. alpine style ascents. We had taken oaths that the first grade six in Colorado deserved our commitment to a classic ascent. Despite knowing that we would pass through bands of rotten rock, we planned not to degrade our attempt with unnecessary bolting or extensive bolting.”

This sense of committing to good ethics and terms of engagement with the landscape is the backbone of the American idea of Wilderness, and embedded in the Wilderness Act, which defines Wilderness as “untrammeled,” “primeval,” and “undeveloped” landscapes, in which humanity is just a visitor. Though Kor, McCarthy, and Bossier weren’t meditating on nature in those explicit terms, their ascent too is wrapped in high-minded reflection on immersion in natural landscapes. After their wet bivvy, nature brought about a brush with awe that is so often what we seek in great, vast, wild adventures: “Next morning, as light became perceptible, we were engulfed in a dramatic whirlwind of dancing clouds. Shafts of light shone vertically upwards from the depths of the Canyon, while other masses swirled and skipped in wave patterns. We sat on our perches awed as light beams and rainbows mingled with mist. They were below us. They were with us—we could reach out and touch them. The clouds died as the power of the sun burned through and we began to take stock.”

No doubt waking up to this kind of light show—their position in the midst of it only possible because of this unique terrain—was part of the transformative experience of this climb. Bossier’s reflections demonstrate again that just as climbers of this time period were grappling with the appropriate boundary for the responsible use of fixed anchors, they were likewise attuned to how the landscapes they were climbing in shaped their experience.

Topo of D1, the first ascent of The Diamond, featured in the September 1960 issue of Trail and Timberline. AAC Library Collection.

D1, The Diamond, Rocky Mountain National Park

Designated Wilderness in 2009

1,010 ft (308 m), 8 pitches, V 5.7 A4, Kamps-Rearick, 1960

Though climbing lore often focuses on tales of breaking the rules and going against the grain, there has been a long history of climbers working within land agency regulations in order to gain sustainable access. The story of The Diamond of Longs Peak, one of the most sought-after walls in the country, is one such example. According to the recounting of the first ascent, published in the 1961 AAJ: “In 1953 a party organized by Dale Johnson of Boulder announced its intention of attempting an ascent of this wall, but was refused permission by the National Park. Since then the Diamond has been ‘off limits’ to climbers. Being thus restricted from the climbing activity going on elsewhere in the country, it gradually assumed the distinction of being the most famous unclimbed wall in the United States.” So when Robert Kamps and David Rearick received permission from RMNP to attempt to climb The Diamond in August of 1960, all eyes were on them.

September 1960 issue of Trail and Timberline, featuring an image from the first ascent of The Diamond. Cover photo by Al Moldvay of The Denver Post. From the AAC Library Collection.

The draw of the Diamond was certainly a sense of ultimate challenge. The altitude and remoteness of this striking wall was a key part of the adventure. Today, D1 is often overlooked, with more accessible lines like The Casual Route and Pervertical Sanctuary getting the most mileage, and lines like Ariana getting the most attention at the 5.12 grade. However, Mountain Project whispers suggest that well-rounded Diamond climbers consider it the best route on the Diamond. So unlike Kor’s The Diagonal, it’s historic and good climbing.

Rearick and Kamp’s three day ascent “was one more dent in the concept of the impossible.” Like many Diamond climbers even today, they battled the weather and a waterfall dripping on their belays and bivvy. But this encroachment of water seemed to be a reminder that though they may be conquering the wall, they were but a small creature in a wilderness that was ultimately untamable. Like so many other climbers recreating in such extreme natural environments, the ascent was inextricably linked to moments of sublime quiet. “The night was clear and we watched the shadows from the moon creep stealthily along the slope of Lady Washington below us and across the shimmering blackness of Chasm Lake. We both managed to doze for a few hours. Since the temperature stayed above freezing, the waterfall continued all night, occasionally splashing us. The altitude at this point was about 13,700 feet.”

Rearick and Kamps placed 4 expansion bolts in total—by hand, of course, which continues to be a requirement for new or replaced bolts in Wilderness—when all other ways of securing a belay were exhausted. This method and their tools had been explicitly reviewed and approved by the National Park beforehand, as a condition of their permission to attempt this famous feature. This incredibly important ascent was just the beginning of a revolution in climbing, as Godfrey and Chelton recount: “the concept of the impossible was seized roughly by the scruff of the neck and shaken up so as to be unrecognizable.”

***

As these three first ascents demonstrate, the roots of Wilderness climbing is often tied up with philosophies of restraint in use of fixed gear, spiritual connection with nature, pushing the limits of the sport, and prioritizing boldness without being unsafe.

That was Then…This is Now…

Much of the discussion around fixed anchors in Wilderness within the climbing community has simplified and erroneously associated the concept of fixed anchors with grid bolting or sport climbing. Some people are kicking around the idea that the only climbing that should happen in Wilderness is the purest kind, like “back in the day”—suggesting that absolutely no fixed gear was used “back in the day.” The history of these iconic Wilderness climbs shows that this narrative is full of misunderstandings. Even when the best climbers of the day refused to “degrade” their ascents with unnecessary bolting or fixed gear, they did apply these tools when necessary for safety. Evidently, Wilderness climbing’s roots lie in a philosophy of responsible and restrained use of fixed anchors to facilitate meaningful experiences and inspire advocates of Wilderness. Now the question is, what is Wilderness climbing’s future?

You can help decide. Share your thoughts on the proposed fixed anchor guidance from the NPS and USFS before January 30, 2024.

Resources:

This article was only possible thanks to the depth of resources from the American Alpine Club Library and historic records from the American Alpine Journal. Want to delve into our extensive historic climbing archives and guidebook library? Check it out.

“The Salathé Wall.” American Alpine Journal. 1963.

“Salathe Wall.” Mountain Project.

Beyond the Vertical by Layton Kor

“The Diagonal.” Mountain Project.

Climb! Rock Climbing in Colorado by Bob Godrey and Dudley Chelton

Royal Robbins: The American Climber by David Smart

The Black: A Comprehensive Climbing Guide to Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park by Vic Zeilman

“The First Ascent of the Diamond, the East Face of Longs Peak.” American Alpine Journal. 1961.

“D1” Mountain Project.

The Line — January 2024

In this month’s edition of The Line, we bring you two brand-new AAJ stories—plus a vintage report that’s had a fresh update.

Suraj Kushwaha leading the final corner on Fissure in Time. Photo: Nikhil Bhandari.

COOL CLIMBS IN NORTHERN INDIA

Rathan Thadi, near Manali, India. Photo: Suraj Kushwaha.

Supported by an AAC Live Your Dream Grant, Suraj Kushwaha from Vermont and Nikhil Bhandari from Hyderabad, India, explored a beautiful granite dome near Manali in northern India. Last spring, Kushwaha had attempted a route on the 4,600-meter formation, dubbed Rathan Thadi Dome, but melting snow soaked the rock and halted the effort. Armed with the lessons from that experience, he returned with Bhandari in October and climbed two beautiful rock routes: Rathan Thadi Direct (6 pitches, 5.11-) and Fissure in Time (6 pitches, 5.10 A2 M2). Kushwaha said the latter would go free at about 5.12-. The two also found some quality bouldering in the valley, the highlight of which was Tehelka (“Chaos,” V6).

In addition to winning an AAC grant, this expedition was the capstone project of Kushwaha’s participation in the Scarpa Athlete Mentorship Program (supported by Mountain Hardwear), which aims to help athletes from historically marginalized communities take their game to the next level. You can download Kushwaha’s complete report on the Rathan Thadi climbs at the AAJ website.

Working on Tehelka (V6). Photo: Kiran Kallur.

THE TRENCH CONNECTION

In early March 2023, Dylan Miller, Seth Classen, and Keagan Walker made a rare winter ascent of the Main Tower (6,910 feet) in the Mendenhall massif, via the standard route up the west ridge. A few weeks later, Dylan and Seth returned with Alex Burkhart and Cameron Jardell for an even more ambitious project: a new route up the south face.

Top: Seth Classen during the descent from the top of the Main Tower after making the first ascent of The Trench Connection. Bottom: The new line. The descent was to the left. Photos: Dylan Miller.

Starting in the afternoon of March 26, the quartet made the 10-mile, seven-hour approach on skis and reached the base of Main Tower at nightfall. Although the temperature soon plummeted, they had planned a nighttime ascent to minimize the solar effect on the deep snow they’d be climbing. Hours later they reached the top of Main Tower after completing The Trench Connection (1,600’, IV AI3 85°). They descended the normal route, using the anchors from their winter ascent three weeks earlier, and skied back toward town, reaching the cars by 10 a.m. on March 27 after a long, frosty night in the Alaskan wilderness. Read Dylan’s story at the AAJ website.

HISTORY: BAINTHA BRAKK II

Baintha Brakk II, the 6,960-meter neighbor of the famous Baintha Brakk (The Ogre) in the Karakoram, was first climbed in 1983 by a Korean team, by the northwest buttress. The AAJ report was scant and, it turns out, had some errors. These have now been corrected thanks to Kim Dong-soo from Korea, who also provided some historical photos from the climb. Two members of the 1983 expedition reached the summit: Lim Deok-yong and Yoo Han-gyu. During the final push above Camp 3, the two had to bivy in a snow cave at 6,800 meters without sleeping bags before carrying on to the top. Read the updated report here.

Climbing at 6,400 meters during the 1983 first ascent of Baintha Brakk II (a.k.a. Ogre II). Photo: Korean Ogre II Expedition.

Baintha Brakk II as seen from Baintha Brakk, showing the line up the northwest buttress attempted in 2015, very close to the 1983 first ascent of Baintha Brakk II by a Korean expedition. Photo: Kyle Dempster.

Many American climbers will remember Baintha Brakk II as the peak that Scott Adamson and Kyle Dempster from Utah attempted twice by the north face. Tragically, they disappeared during their second attempt, in 2016. One year earlier, Marcos Costa (Brazil) and Jesse Mease (USA) made a four-day, alpine-style attempt to repeat the Korean route on Baintha Brakk II, finding very difficult climbing before retreating at 6,700 meters. Although conditions undoubtedly were different three decades after the first ascent, the photos from 2015 are ample testimony to the difficulty of the ground the Korean team climbed in 1983.

Most reports older than 2010 in the AAJ online archive are not accompanied by any photos. If your climb was published in the AAJ before 2010, we invite you to submit photos to update our online stories and complete the historical record. Contact us at [email protected].

THE CUTTING EDGE PODCAST: WHITE SAPPHIRE

For the final episode of the Cutting Edge podcast’s 2023 season, we interviewed Christian Black, Vitaliy Musiyenko, and Hayden Wyatt about their new route on White Sapphire, a peak in northern India’s spectacular Kishtwar district. Supported by a Cutting Edge Grant from the AAC, the three climbers put up Brilliant Blue (850m, AI3 80°M7+), probably making the third ascent of the 6,040-meter peak. Two of the three climbers had never been to the Himalaya, and this interview captures their wide-eyed enthusiasm, as well as their ability to go with the flow—a critical element for success in the Greater Ranges. Listen here.

Sign Up for AAC Emails

The Line is the newsletter of the American Alpine Journal (AAJ), emailed to more than 80,000 climbers each month. Find the archive of past editions here. Contact Heidi McDowell for sponsorship opportunities. Questions or suggestions? Email us: [email protected].

The Line is Supported By

CLIMB: Tom Evans and Two Decades of Reporting on El Cap Climbing

Tom Evans on El Cap back when he was climbing it instead of reporting on it.

New episode of the American Alpine Club Podcast with legend Tom Evans:

Tom Evans is the creator of the El Cap Report. He started out taking photos of all the climbers he’d see on El Cap, and got tired of answering questions about who was doing what and how X ascent was going. So he innovated. He started posting a daily report, accompanied by his photos, of what was happening on El Cap during the main Yosemite climbing season—and he since has crafted a legacy of 22 years of documenting “the center of the universe”—El Cap climbing. With his recent retirement from the El Cap report, we decided we wanted to celebrate this legacy, and hear all his thoughts on the climbing history he’s documented, witnessing accidents and rescues, what’s next in El Cap climbing, the impact of social media in the Valley, and what motivated him in the first place to create the El Cap report. Dive in to get to know one of the legendary names from the El Cap bridge scene—a conversation just for you, unique in all the world!

Tom Evans in Action: Climbing and Documenting the “Center of the Universe”

The Prescription—January 2024

A note from the editor of Accidents in North American Climbing: I’m writing this from the AAC Hueco Rock Ranch in Texas. Here, the season is in full swing for what some say is the best bouldering on the planet. While often regarded as relatively risk-free, bouldering can be plenty dangerous. This month we feature a reminder from Joshua Tree National Park.

The Hidden Valley Area of Joshua Tree National Park. This popular expanse holds a vast number of classic boulder problems, including White Rastafarian (V2-3,PG-13). Photo: Wikimedia Commons NPS/Hannah Schwalbe.

Bouldering Fall | Insufficient Pads

California, Joshua Tree National Park, Hidden Valley Area

On November 9, 2023, Gibson McGee (19) was bouldering on White Rastafarian, a V2 (often graded V3) highball that has been the scene of many accidents. He fell from near the top and struck the ground, shattering his L1 vertebra, the highest bone in the lower back.

Though Mountain Project describes White Rastafarian as “one of JTree’s finest (problems),” the climb is 25 feet tall—more a short route instead of a boulder problem. After the midpoint crux, the climber is faced with a tricky mantel topout.

Victor Pinto topping out on the classic White Rastafarian. John Long, who did the first ascent of this iconic highball with John Bachar, wrote of their experience in Climbing magazine, “Once we passed a precise but invisible line, we were soloing, plain and simple.” Photo: Victor Pinto.

McGee wrote to ANAC, “I was heading to Joshua Tree for the weekend, and I was planning on meeting a group who were coming in the following morning. After setting up camp, I went to go climb the nearby White Rastafarian. I had previously attempted it but fell at the crux (15 feet off ground). I was fine with no injuries.” McGee laid out three crash pads, set up a video camera to record himself, and started up the route.

Graphic Video Warning

At Accidents in North American Climbing we refrain from publishing gratuitous depictions of injury. However, to convey the real risks of an activity that many people consider relatively risk-free, we are providing a link to Gibson’s Instagram account:

See his video here.

“I got to the top of the route (about 25 feet off ground) and was too pumped to do the ‘easy’ mantel onto the top of the rock. I looked down and decided I could drop safely. I dropped, but when I hit the ground, I ended up shattering my L1 vertebra. I then army crawled (using arms and upper body to cross the ground) to the nearby Hidden Valley Campground, where I got help and was transported by ambulance to High Desert Medical Center.”

McGee is currently recovering. He wrote, “While I am eager to be able to climb again, healing physically and mentally from this fall will take me quite some time. I was very fortunate looking back on the possible injuries I could’ve sustained.”

Analysis

Bouldering is inherently dangerous, and highball problems particularly so. On Reddit, un poco lobo posted, “Was chatting with a park ranger who said they see more accidents on WR (White Rastafarian) than pretty much all other routes/problems combined.”

A Similar Accident

For another Joshua Tree bouldering accident involving inadequate pad placement, click here.

McGee had been consistently climbing outdoors for one year prior. He recalls, “I saw White Rastafarian the first week I started climbing. It has always been a dream for me to do it.” His pad placements were in the right place and he landed cleanly—no part of his body struck exposed ground. While multiple pads are great idea, an evenly distributed second layer of pads might have saved McGee from a trip to the hospital. Covering gaps between pads with a thin “slider” pad also would have provided additional safety. McGee mentioned, “I should’ve brought a buddy and stacked bouldering pads.”

Keep ‘Em On The Pad!

In bouldering, spotting is the norm. On highballs, though, spotters can be extraneous as the impact forces of a falling climber can be equally harmful to the spotter. See a fall from the same problem that came close to injuring the spotter here.

While spotting highballs is more art than science, the general rule is to ensure the falling climber stays on the pad after impact. Guaranteeing that the climber impacts the pad itself is part of good pad placement. A spotter should also protect the head and neck from impacting bare ground or surrounding obstacles. Another good rule to follow is to never fall above the 20-foot mark. Be open to using a top-rope to practice the problem. John Gill himself was a big exponent of top-roping.

Finally, Joshua Tree has a well-earned reputation for tricky climbing and a long learning curve. As always, different climbing areas have special characteristics that grades do not convey. Be conservative and risk-averse as you learn the peculiarities of any area. Wrote McGee, “I have bouldered in Joshua Tree four or five times. The grading is much, much harder than what you might think. I let the number (V2-3) get in my head rather than trusting the true difficulty of J Tree grades.”

(Sources: Gibson McGee, Mountain Project, and Climbing magazine.)

Clarification and Reflection on Michael Spitz Free Solo Accident

In the 2023 ANAC, we reported on the death of free soloist Michael Spitz. Recently, Brian Gillette, a close friend of Spitz, reached out to correct some inaccuracies in our report. In his letter to ANAC, Gillette filled some gaps in our understanding of the accident, while offering some thoughtful words on risk.

A short excerpt, “In the year before his death, Mike's free soloing had accelerated from an occasional outing to a nearly weekly activity. The more he free soloed, the more I watched his perception of the risks become disconnected from the reality of climbing. Mike had also been surfing a heavy swell in the days leading up to his death. When I spoke with him the night before, I thought he sounded tired and told him to take it easy. He told me he planned to climb for the day and head home. From what I can tell, soloing Illusion Dweller was a last-minute decision. He might have been more tired than he realized. It might explain why a small slip caused him to fall. Mike's last-minute decision also meant that he wasn't prepared in any way for a potential accident, even a minor one.”

Read the original report and Brian Gillette’s full letter here.

Sign Up for AAC Emails

The Line — December 2023

Lots of rock: The gorgeous view from a beach campsite along Khor Ash-Sham. Photo: Marius Rølland | @unrealmarius

THE NORWAY OF ARABIA

“From our campsite at the edge of the Khor Ash-Sham (Ash-Sham Fjord), on yet another deserted white-sand beach, we watched the sun sink low over the Strait of Hormuz. A single thought occupied our minds, and Aniek was the first to put it to words: ‘I don't want to leave tomorrow.’”

Alan Goldbetter, who wrote this passage for AAJ 2024, spent eight days last January with Aniek Lith and Marius Rølland exploring Khor Ash-Sham in the Musandam Peninsula of Oman: “kayaking with dolphins, wading shin-deep through bioluminescent algae, climbing multi-pitch routes on virgin limestone, and giggling the nights away under a shimmering, star-filled sky.” Their two new routes, each 5.10 and more than 1,000 feet long, were the first recorded roped climbs in the fjord. Read Goldbetter’s AAJ 2024 report to learn more.

Evening fun: After a day scrambling a ridge on Khor Ash-Sham fjord’s north side, the team prepares to bivy. Photo: Marius Rølland |@unrealmarius.

CLIMBS IN CANADA’S ARJUNA SPIRES

Daniell Councell moving up easy ground near the start of the Quartz Arête, the first known route up Nakula Spire, whose summit towers high overhead. Photo: Andrew Councell.

Starting the upper buttress on Nakula Spire. Photo: Andrew Councell.

Heli-skiing guide Andrew Councell had ogled the rocky peaks around Bella Coola, British Columbia, for years while flying into the mountains to ski, but the few roads and desperately steep hillsides in the area severely limit summertime access. “Finally,” Councell writes in an AAJ 2024 report, “in a culmination of years of desire to climb these mountains, mixed with a fatalistic shrug toward my bank account, I planned an exploratory trip with my brother Daniel.” A 10-minute helicopter flight landed them at a luxurious base camp by the Arjuna Glacier.

The result was the probable first ascent of two formations in the Mt. Arjuna massif, along with a handful of shorter routes and a rare climb of Arjuna itself. The highlight was the Quartz Arête on the north side of Nakula Spire, a beautiful buttress with mostly moderate climbing and a crux of 5.9. “My hope,” Councell writes, “is that continued development of climbing in the Bella Coola backcountry will encourage fellow adventure seekers to discover this untapped arena.”

PUNCHING A ROUND TRIP TICKET

This month’s Cutting Edge podcast interview with Matt Cornell, Jackson Marvell, and Alan Rousseau, about their alpine-style new route up the north face of Jannu (Kumbhakarna) in Nepal, is understandably one of the show’s most popular episodes in years.

One thing we didn’t get to in the hour-long interview is the origin of the new route’s name, Round Trip Ticket, which has an interesting and telling backstory. In 2007, Valery Babanov and Sergey Kofanov climbed the west pillar of Jannu, a remarkable climb in its own right (also climbed alpine-style). A decade later, Kofanov wrote in an Alpinist magazine Mountain Profile about Jannu: “Perhaps someday, a pair will climb a direct route on the north face in alpine style, but they’ll need to accept the likelihood that they’re buying themselves a one-way ticket.” As you’ll hear in our interview, the three American climbers’ planned itinerary was round-trip all the way.

The Line is the newsletter of the American Alpine Journal (AAJ), emailed to more than 80,000 climbers each month. Find the archive of past editions here. Interested in supporting this online publication? Contact Heidi McDowell for opportunities. Questions or suggestions? Email us: [email protected].

Sign up for AAC Emails

“The Line” is Supported By

Measuring Success in the Mountains

PC: Lindsey Hamm

A Story from the Cutting Edge Grant and the McNeill-Nott Award

By: Sierra McGivney