Rappelling was once considered a prerequisite skill for any climber navigating 5th class terrain. It was a mainstay of introductory texts, climbing classes, and novice climbers were often taught to rappel before they ever climbed their first pitch.

Much of that has changed, and large numbers of climbers enjoy all kinds of outings where rappelling is both unnecessary and perhaps unwise. Many toprope venues do not require rappelling during setup, many sport climbing venues are equipped to quickly clean anchors by lowering, bouldering usually does not require any form of technical ropework (much less rappelling), and most modern climbing gyms flatly disallow rappelling. As a result, rappelling is something that many climbers understand conceptually (having lowered each other) but fewer have actually experienced. As a result, when rappelling accidents happen to beginners we often discover that the contexts of rappelling were not perfectly understood, the fundamental physics of rappelling were confused, and the variability of the rigging was understated or oversimplified by mentors and instructional materials.

A generation ago, every climber learned to rappel. Early rappel techniques, like the Dulfersitz, helped climbers learn the relationship between the body and rope friction. These techniques still work, but they don't provide many options for backups or added security.

By comparison, experienced climbers have often rappelled hundreds or thousands of times, but an unfortunate number of us also seem to be randomly involved in rappelling accidents. In these cases, preventative practices like knotted rope ends, using backups, and a system of careful double-checks were often overlooked or ignored, even though the value of these techniques is undisputed.

In this article, we hope to create a resource for novice climbers to understand what rappelling is, the contexts in which it happens most commonly, and a set of principles that should govern the rigging. We also hope to address any reader that may be well into their rappelling career. Perhaps some will find reasons to adopt practices that they have historically ignored, or revise the practices they are currently committed to using regularly. In some cases, this article may simply validate what a reader is already doing, but in that case we hope it might also give them a vernacular for communicating with their friends, students, and mentees.

What is rappelling?

To put it most simply, rappelling is just lowering your own mass down a climbing rope. In belaying, the belayer remains stationary and the rope moves. In rappelling, the rope remains stationary, there is no belayer, and the rappeller is the thing that is moving.

Once a climber has rappelled a few times, these distinctions seem painfully obvious. But, as thousands of climbing instructors will attest, until a person has experienced the fundamental difference between being lowered and rappelling, it’s not obvious at all. A rappeller has independence, agency, and control in a way that a person being lowered does not. That can be advantageous, but it also means that rappellers sometimes lose the advantages and redundancy of team work.

There are two main variations to rappelling mechanics: fixed-line rappelling and counterweight rappelling. In fixed line rappelling, a climbing rope is connected to an anchor, the rope remains stationary, and the rappeller can rappel all the way down to the other end of the rope. In counterweight rappelling, a climbing rope is not fixed. Instead the rope runs freely through a rappel station, set of carabiners, or around an object. In this arrangement, a rappeller must capture both strands of rope within the rappel in order to counterweight around the rappel anchor point, and the rope can be retrieved from below.

In counterweight rappelling, a rope runs freely through a rappel fixture. As a result, a rappel device must capture both strands of the rappel rope. The rappeller effectively counterweights themselves.

In fixed line rappelling, the rappel rope is affixed to an anchor, so the rappeller does not need to effect a counterweight. The rappeller can rappel a single strand of rope.

When do climbers rappel?

Climbers rappel for two main reasons, in two primary contexts: single pitch rappelling and multistage rappelling. Both options are slightly different, and a climber learns to adapt the rigging, the device selection, and the anchoring accordingly.

Multistage rappelling happens when climbers ascend a multipitch climb and descend the feature through a sequence of rappels. They climb a big wall, up up up, in sections, and then they rappel, down down down, in sections.

Single pitch rappelling. Climbers also occasionally rappel when they clean anchors in a single pitch setting. Sometimes, local custom or policy require climbers to rappel when they clean. Sometimes, lowering is not an option. Sometimes, rappelling is needed in emergencies.

“The first step in avoiding any climbing incidents is good prior planning. Get all the information you can from the guidebooks. It is also a good idea to take a copy of a route topo—even if you have done the route before. And consider looking at blogs and talking with friends or acquaintances for information.

Equipment inspection before each season—and before each climb—is always important. Is it time to retire your ropes, slings, or harness? Look closely at all the gear to see if there are any obvious wear and tear issues and consult the manufacturers for recommendations.

Double-check any critical system carefully before committing to it. Look through and inspect all critical links, carabiners, the rope’s integrity, the harness’ key points (buckles, belay loops, and connection points). It’s always helpful to have a partner nearby so that climbers can double check each other.

Decide how the climbing team will communicate before the need for communication arises, minimize the amount of words needed to relay information unambiguously, and focus on communications that initiate action.”

Fundamental Principles of Rappelling

You should be secure during the setup because rappels are often rigged in proximity to cliff’s edges and precipices, and even careful and experienced climbers are endangered by that kind of exposure.

You should use appropriate backups because a variety of factors make it likely that a rappeller will lose control of the rappel.

You should manage the ends of the rope because we often rappel in the dark, when tired, with unfamiliar ropes and in unfamiliar terrain, and since we often rappel rapidly, the ends of the rope can present a unique hazard.

Avoid Entanglements. Rappelling involves a lot of rope that must be carefully managed and rappel devices that notoriously entrap hair, hoody-strings, straps, and clothing, the last principle asks us to manage the rope and manage ourselves to avoid entanglements.

Security During Setups

There are lots of ways to be secure during setup. Generally, the options fork into two initial categories: technical and non-technical. Non-technical security does not involve anchors or tethers or carabiners. It’s simply staying away from a cliff’s edge or staying seated when setups are awkwardly close to a cliff’s edge.

Technical security uses some sort of tether, sling, PAS, or the climbing rope to connect the climber to an anchor during setup. The context of the rappelling usually inspires a wide range of variations among the tethering methods.

With their back turned towards a precipitous cliff's edge and their attention focused on setup tasks, these climbers are using technical security (a tether and locking carabiner) to stay secured during setup.

“Notes on appropriate set up:

Be sure that the rope actually passes through the rappel device properly, that a bight includes the carabiner and that the carabiner / extension is properly attached to harness. If pre-rigging – all partners get eyes on each other’s systems.”

Appropriate Backups

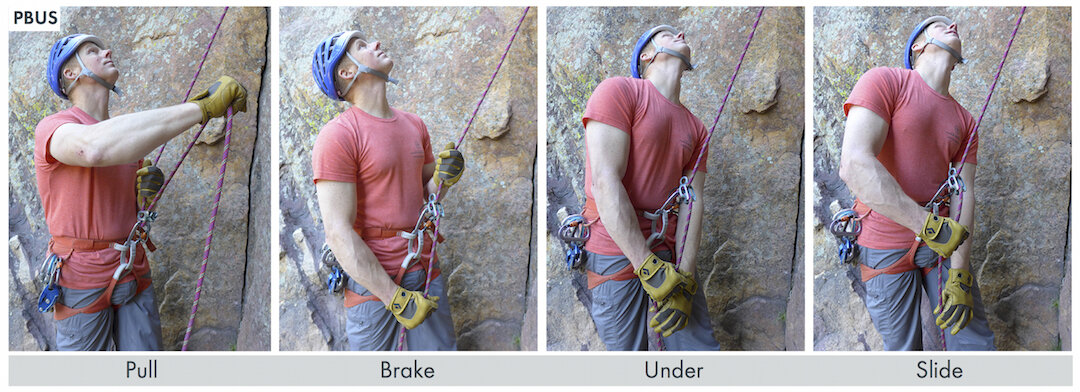

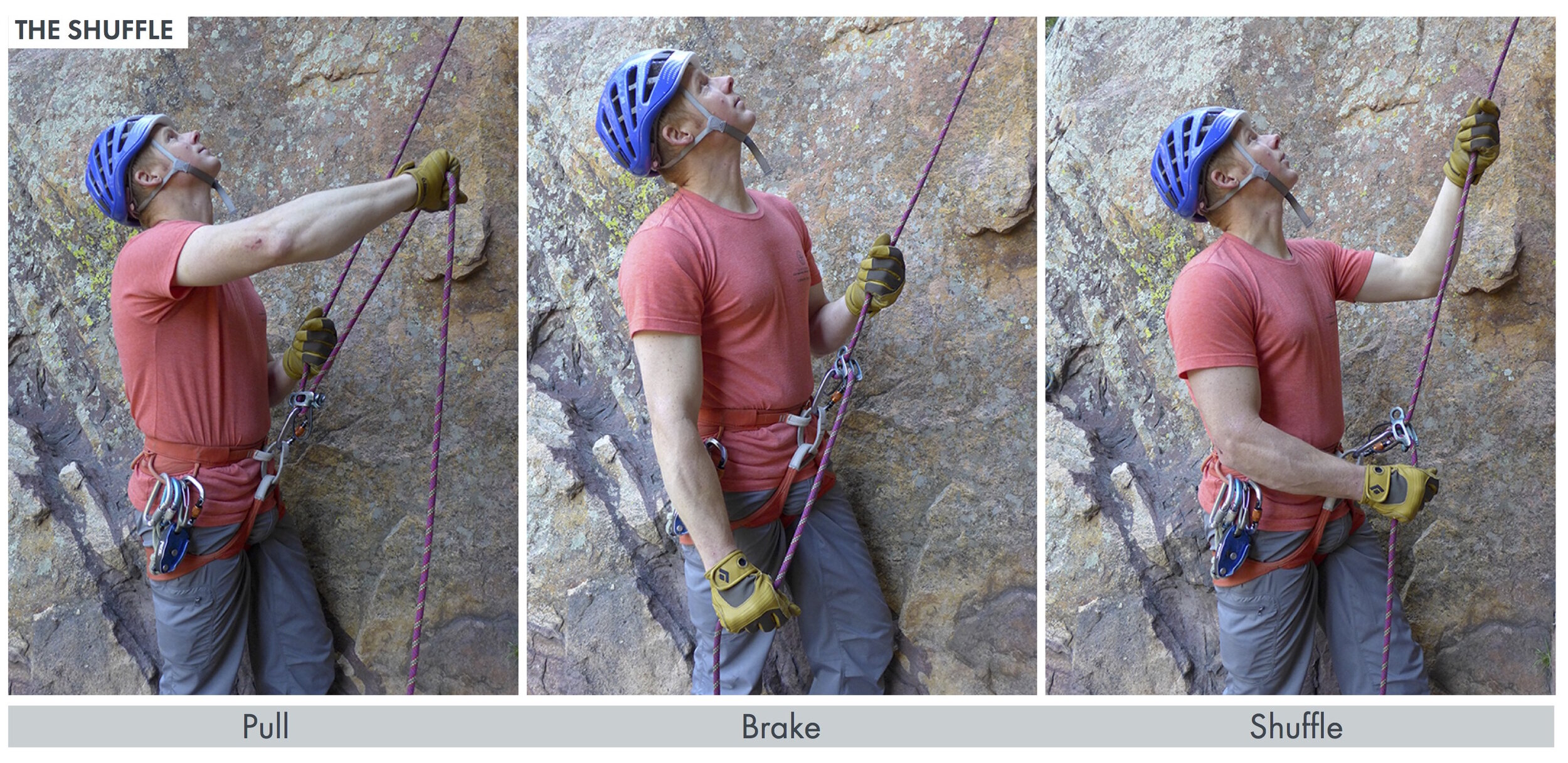

A rappel backup effectively provides a backup for the rappeller’s brake hand. If the rappeller were to release their grip of the brake strand for any reason (losing control, rockfall, medical emergency) the backup would effectively hold the rope instead of the rappeller’s brake hand. There are three common variations: a friction hitch backup, a firefighter’s belay, or the use of an Assisted Braking Device.

Friction Hitch Backup

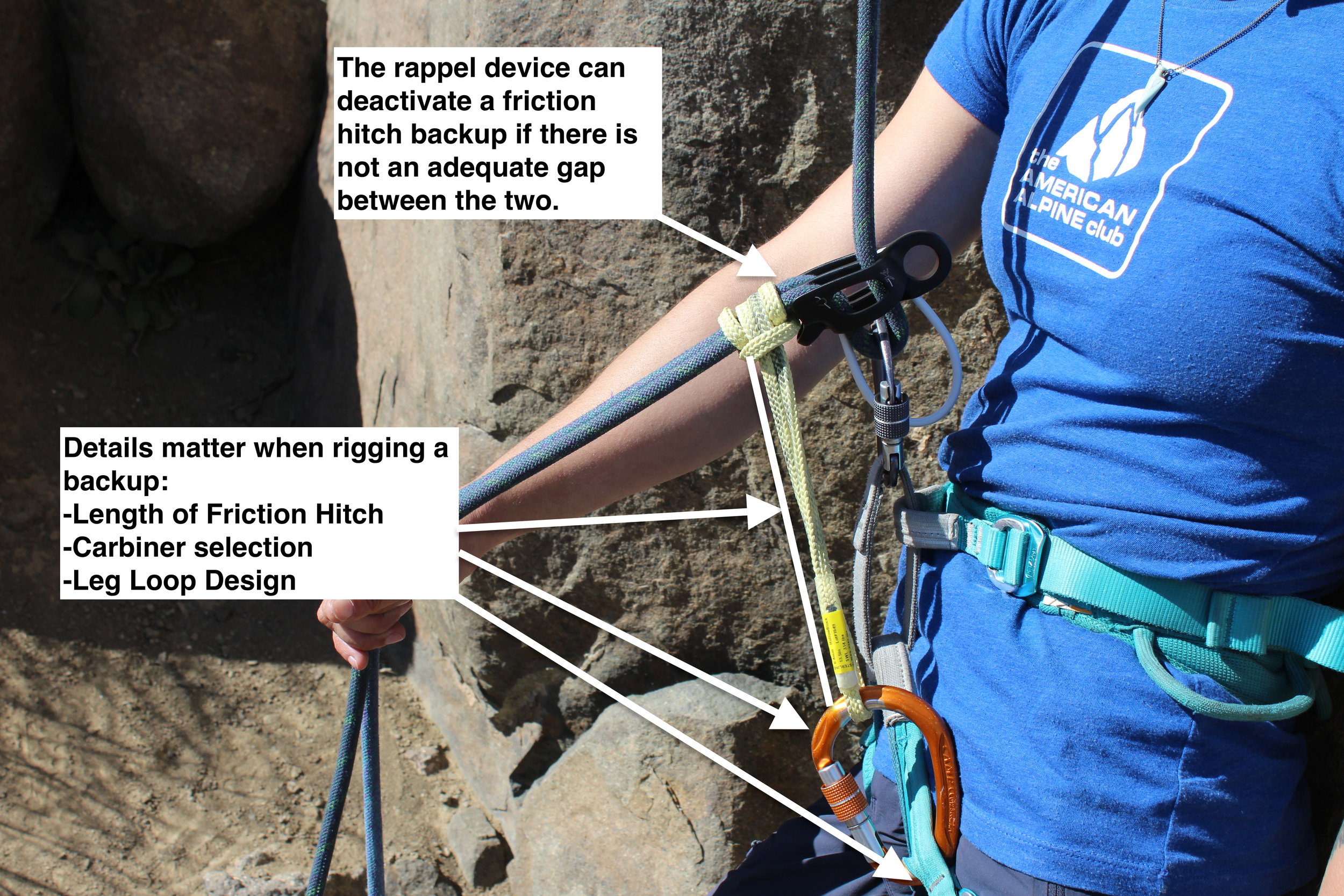

A Friction Hitch Backup can be quickly paired with any tube style rappel device, but the setup has to be precisely configured. If a backup doesn't work when you need it to, it constitutes little more than wasted time, material, and effort. Common examples include friction hitch backups that are poorly dressed, iced or frozen, or they don’t assert enough friction to grip the brake strands with adequate braking power. Also, if a friction hitch backup is too long, it will push up against a rappel device, pushing the hitch along instead of allowing it to grip the brake strands. It’s important to get the lengths just right so that the backup engages. On steeper rappels, an inverted rappeller can easily bring the friction hitch into dangerous proximity to the rappel device.

Precise rigging is vital to an effective rappel backup. It's not enough to apply a friction hitch; the distances and positions of all the pieces have to be just right.

When we don't pay attention to the details, when the rigging is imprecise, our backups are ineffective. This climber has wasted a lot of time and energy rigging a backup that won't work.

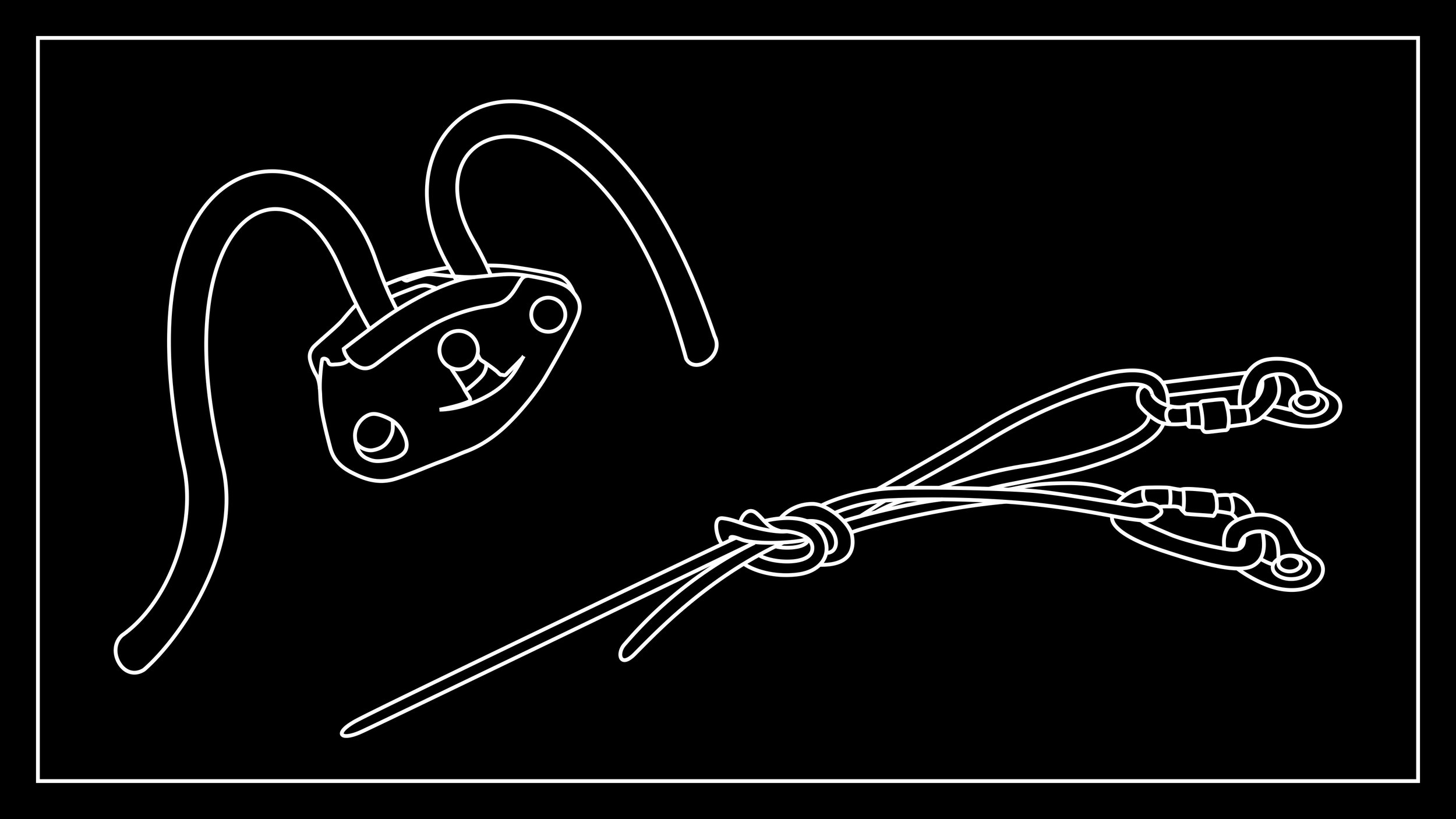

Since the rigging of friction hitch backups has to be so precise, many rappellers prefer to extend their rappel devices away from their harnesses. In this configuration, the friction hitch backup can be connected directly to the belay loop. In general, extensions allow for a greater margin of error in the rigging of rappels and their backups, which is advantageous.

An extension built with a double length nylon sling positions a rappel device far enough from a belay loop that almost any friction hitch backup will be effective.

An autoblock friction hitch is a great option when tying a rappel backup. A small loop of 5mm nylon can be quickly deployed for the task.

The auto block is tied by enwrapping the brake strand(s) of the rappel, as many times as the material length allows...

...and the autoblock is completed by rejoining the nylon loop with the locking carabiner.

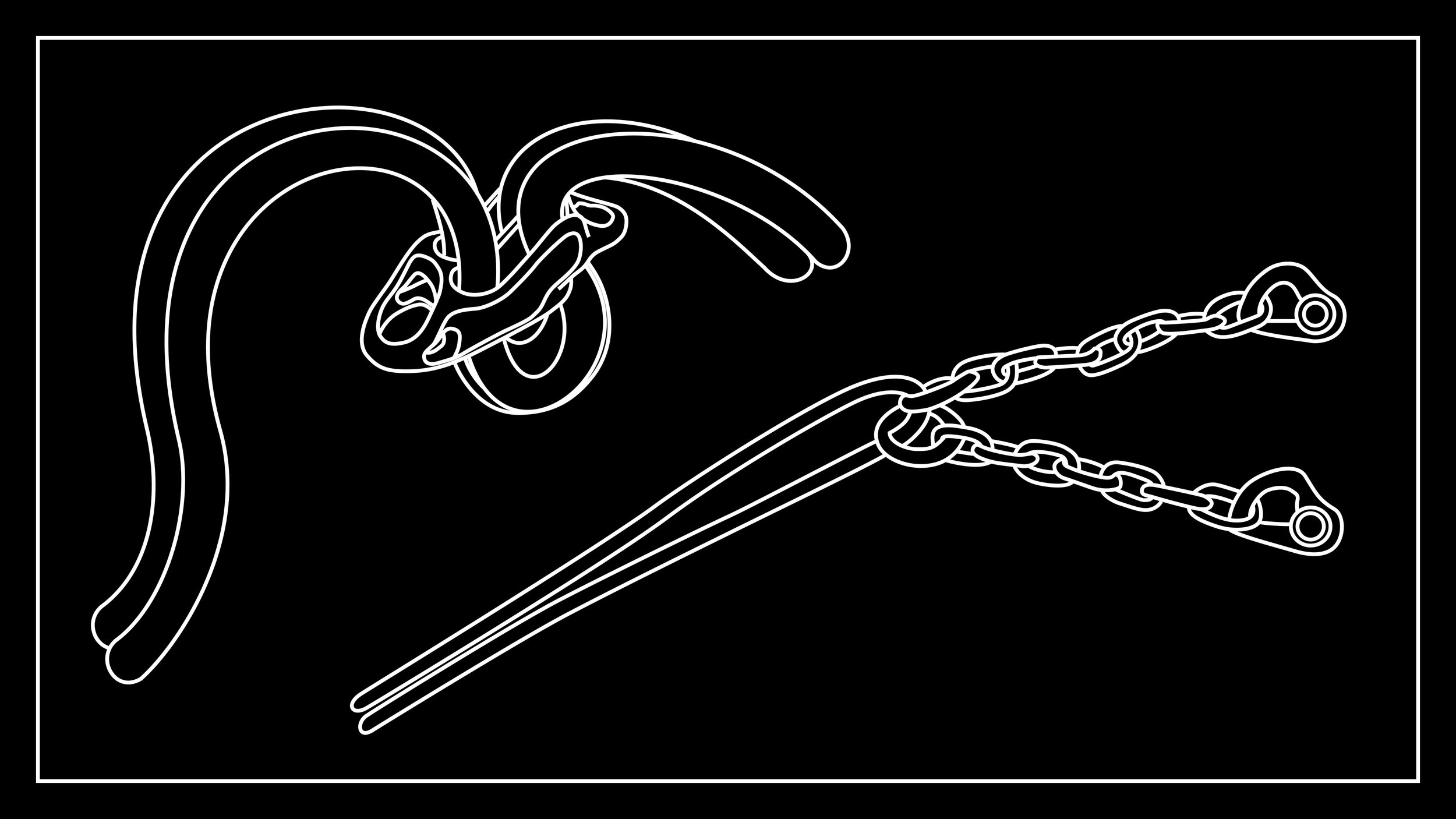

There are eternal debates about the type and style of extension used to separate a rappel device from the harness. Suffice it to say, there are many adequate options. As long as the option is adequately strong and secure, without compromising overall efficiency, it's probably a good one. Some of the most common alternatives include a Personal Anchoring System (PAS) or quickdraw with locking carabiners. For multipitch rappelling, an extension that has a modular leg can be used to both extend the rappel and clip into anchors during rappel transitions.

An offset extension is great for multistage descents.

Firefighter’s Belay

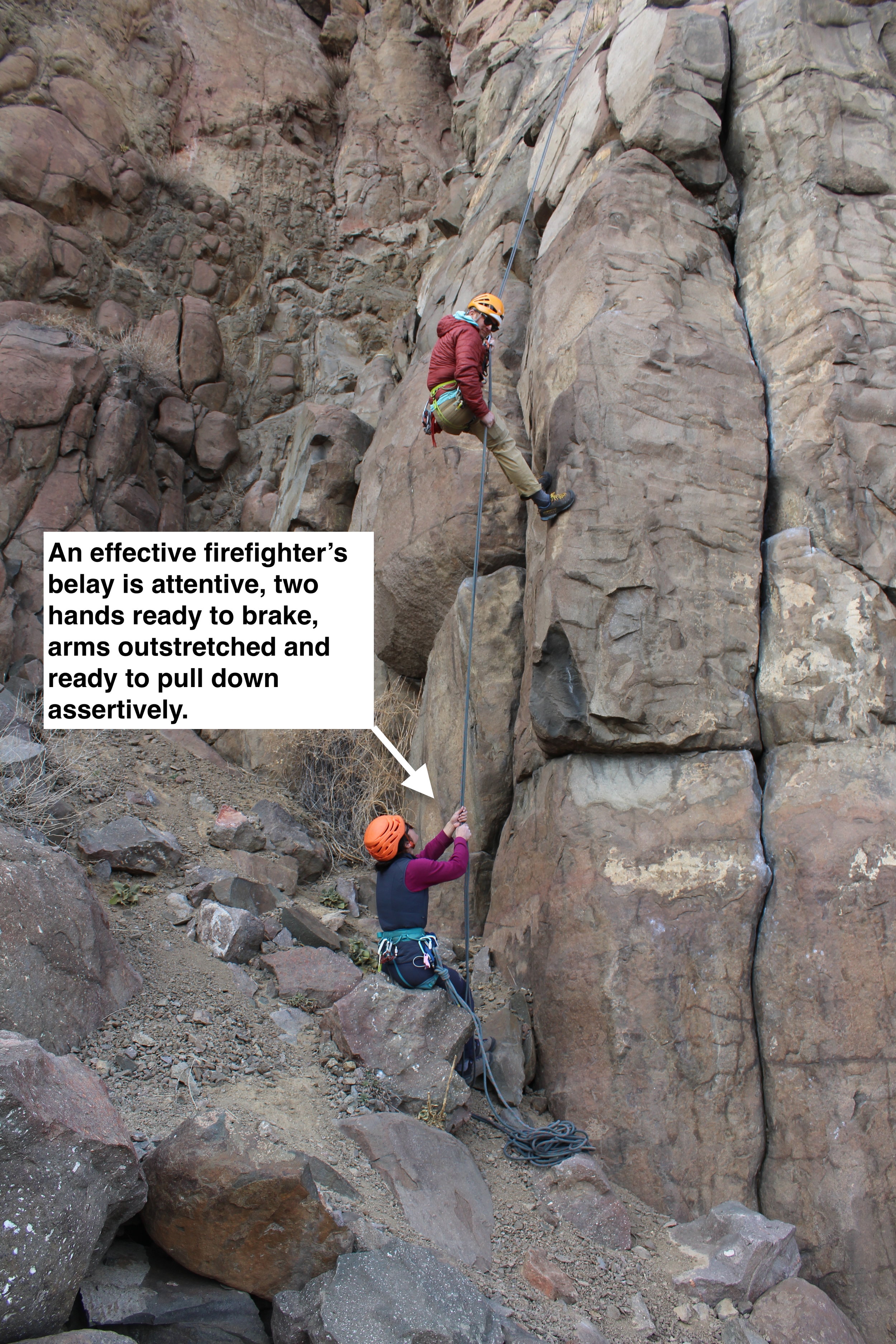

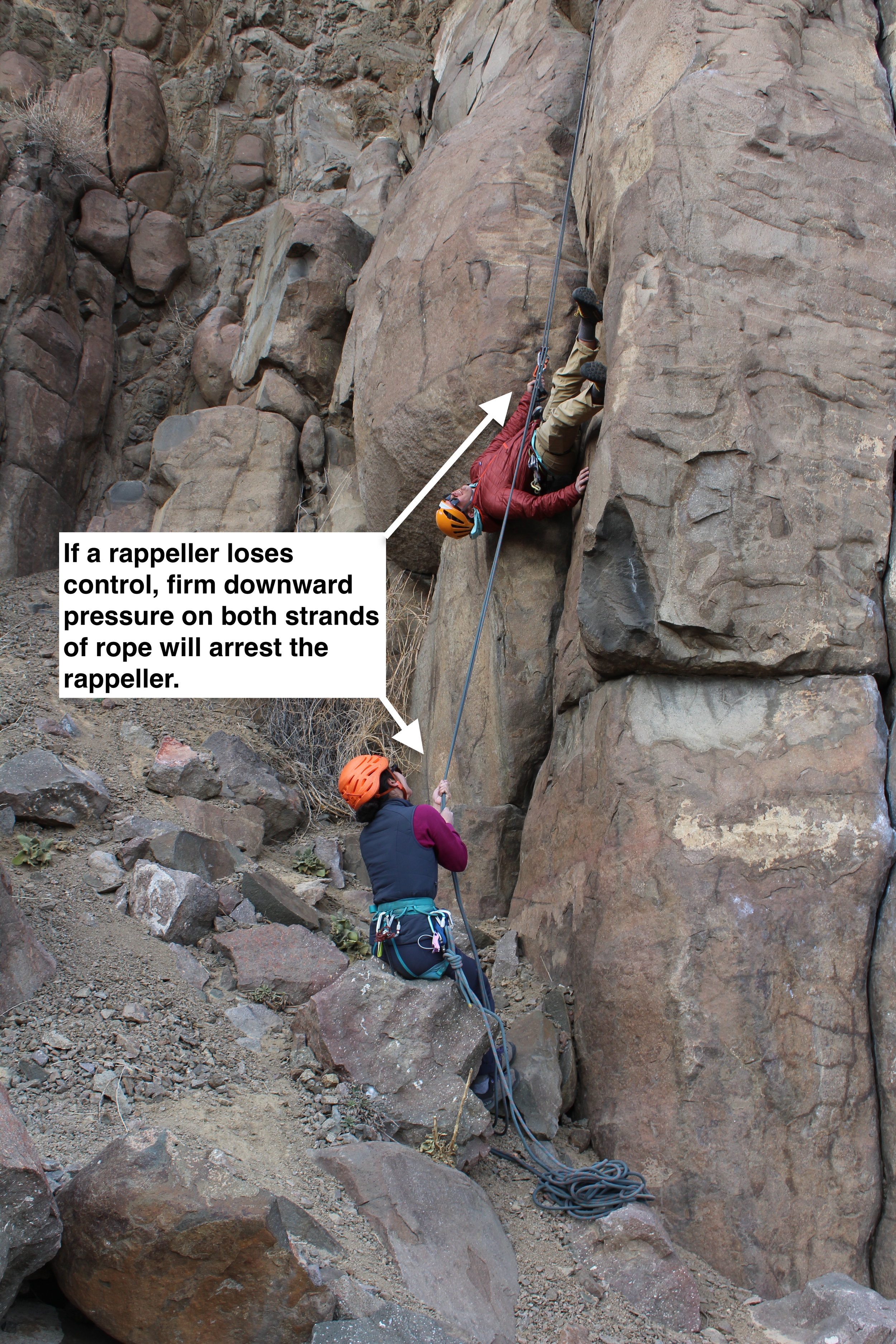

Firefighter’s Belays are effective backups too, but they have to be executed correctly. To provide a firefighter’s belay, the belayer should be attentive, with eyes on the rappeller and hands on the brake strand(s) of the rope. If the rappeller were to lose control of the rappel, the attentive belayer would pull down assertively on the brake strand(s) in order to effect enough braking force to halt the rappeller’s descent. Much like a poorly rigged friction hitch backup, a firefighter’s belay that is inattentive, loose, or off the fall line will likely be ineffective.

When this climber offers a firefighter's belay, she means it. She's attentive and ready to halt the rappeller at any moment.

When rappellers lose control it happens quickly and unexpectedly, but a quick and firm tug on the brake strands will bring the rappeller to a halt.

Managing The Ends of the Rope

Managing the ends of the climbing rope is often a vital technique to keep rappellers from rapping off the end of the rope. Commonly, the ends of the rope are either conjoined or bulky stopper knots are tied, such that the knot that would ram into a friction hitch or rappel device, reliably arresting the rappel.

A pair of bulky stopper knots are among the easiest ways to manage the ends of the rope.

Conjoining the rope ends and carrying them to the ground has the added advantage of managing the ends of the rope while also avoiding tossing ropes down the cliff.

Avoid Entanglements

It’s important to keep anything from getting snagged in a rappel tool, and it’s also important to keep one’s ropes organized and moving fluidly. Entanglements of hair, clothing, or the rope can create serious problems while rappelling, especially in adverse conditions.

Tossing Ropes

It is rarely necessary or expedient to throw ropes down a cliff. Often, the tails of rope can be gently lowered to the ground, or a bight of rope can be lowered and the tails carried to the ground by the rappeller. It’s also likely that tossed ropes will land on other climbers, in places that are difficult to retrieve (trees or cracks), or places that are awkwardly gross (mud, poop, carrion, etc). A rappeller can avoid entanglements by avoiding tossing ropes.

Conclusion

It is a worthwhile thought experiment to imagine how climbers create margins of error, how we use backups, and how/when we selectively (and hopefully carefully) disregard those techniques. Typically, a climber navigating 5th class terrain uses a rope system to mitigate the risk of ground or ledge impact, but sometimes we intentionally neglect to place enough protection to effectuate the rope system we’re tied to. Those are enormously risky behaviors, but we tend to engage in them quite readily when we perceive there to be a low probability of incident, like when the climbing is easy or unremarkable. Similarly, a small portion of climbers free-solo in 5th class terrain, and their calculation is identical: they perceive there to be a low probability of incident, and they therefore eschew a rope system altogether.

The indisputable reality is that good climbers fall off of easy terrain every year. Experienced rappellers lose control, rap off the ends of rope, or incorrectly rig their rappels. As a species, humans don’t always reconcile their rational/analytical response to risk with their intuitive/emotional response. As a result, best practices like using backups, managing the ropes ends, staying secure during setups, and careful double checks are often characterized as overly conservative, burdensome, and slow. Similarly, eschewing these practices altogether, which is actually tantamount to free-soloing in a demonstrable ways, can be characterized as a matter of preference, style, or status.

Instead, take the time to appreciate that each rappel is merely similar to all previous rappels. In quantifiable ways, every rappel is also dissimilar to all previous rappels. If that is true, the way we rappel is also merely similar to the way we rappelled on every previous occasion. The solutions we use to descend our next rappel will be unique in appreciable ways. So, the fundamental principles of rappelling can be used as a unique questionnaire for every rappel. A rappeller should have compelling and accurate responses to each of these questions before rappelling: