The following article is reproduced from the 2016 edition of Accidents in North American Climbing. Author: Ron Funderburke.

Climbers have been belaying for as long as they’ve been using ropes. We use some type of belay in almost every roped climbing context—it is the essential skill that unites all disciplines. It’s interesting, therefore, to see how little agreement there is about the “best” belay techniques, how distracting our assertions about belaying tend to be, and how rigidly dogmatic we can be about a task that many understand so imperfectly.

This dogmatic approach persists even though using a rope to belay something valuable—whether a load of cargo on a ship or a climber on a cliff—has always been organized by three fundamental principles:

There should be a brake hand on the rope at all times.

Any time the brake hand slides along the rope, the rope should be in the brake position.

The hands and limbs should be positioned according to their natural strength.

These are the principles that we should use to evaluate belaying, yet our discussion of “good” or “bad” belaying often revolves around a specific biomechanical sequence. It’s time to abandon this way of talking and thinking about belaying. It’s misleading, reductive, and provokes more arguments that it solves.

Meanwhile, a cursory perusal of any edition of Accidents reveals there are severe consequences for imprecise understanding of belaying. In recent years, 5 to 10 percent of all incidents reported have involved inadequate belays.

This edition of Know the Ropes will equip readers with language and principles that unify all belay contexts. Additionally, for those who are new to belaying, those who want to learn to belay in different contexts, or those who aren’t sure about their current technique, this article will provide some suggestions for how to do so in a fundamentally sound way.

THE ORIGINS OF BELAYING PRINCIPLES

The earliest belayers used the most primitive technique: The belayer held the rope tightly and did not let go under any circumstance. Belayers had to be very strong, and the rope had to be kept very tight. And the brake hand had to be on the rope at all times. Even the strongest belayers and the lightest climbers wouldn’t stand a chance without this fundamental principle.

The addition of friction to the belay system allowed smaller belayers to secure bigger climbers. Wrapping the rope around features in mountain terrain or the belayer’s body provided enough friction to hold larger loads.

Friction also introduced two new realities to belaying. First, friction could be increased and decreased, creating a “belay cycle.” Increased friction is valuable when holding a load; decreased friction is valuable when trying to move rope through the system.

The second new reality was that friction allowed the belayer to relax a little. In the more primitive form of belaying, without friction, the belayer’s hand-over-hand technique maintained a constant grip on the rope. By contrast, a belay system with friction allows the belayer to relax [their] grip at some points in the cycle, which, naturally, deprioritizes vigilance.

These changes led to the second fundamental principle of belaying: Since every belay cycle has a point of high friction, it makes sense to spend as much time in that position as possible. Therefore, whenever the brake hand slides along the rope, the rope should be in the brake position. If a climber falls while the brake hand is sliding on the rope, it obviously will be easier and quicker to arrest the fall if the rope is already in the brake position.

Since the addition of friction to the system, every major evolution in belaying has involved some sort of technology. First came the carabiner, which not only allowed belayers to augment their friction belays but also invited the use of hitches, tied to carabiners, as belay tools. The most effective of these was the Munter hitch.

The Munter hitch offered a braking position that was the same as the pulling position, so the belay cycle was easy to teach and learn. It soon became the predominant belay technique in all disciplines. (Before the advent of reliable protection, dynamic belays, and nylon ropes, belaying was primarily the duty of the leader. A second might belay the leader, but the leader was not expected to fall, nor was it widely expected that a leader fall could be caught.) The Munter hitch, belaying a second from above, conforms naturally to the third fundamental principle of belaying: It positions the hands, limbs, and body according to their natural strength. It keeps the belay comfortable and strong throughout the belay cycle, and while taking rope in, catching falls, holding weight, and lowering.

THE MODERN ERA

An era ago, these fundamental principles were not really in dispute. They applied to body belays (hip belays, butt belays, shoulder belays, boot-axe belays, etc.), terrain belays (belays over horns, boulders, and ridgelines), and belays on carabiners (Munter hitch). However, by the Second World War, climbers began to use nylon ropes and other equipment that could handle the forces of leader falls. Moreover, climbing clubs, schools, and enthusiasts began to experiment with redirecting the climbing rope through a top anchor, so that belaying on the ground, for both the leader and follower, became much more common. Pushing the limits of difficulty also became more common— leading to more falling.

Belayers around the world also began to experiment with new belay tools that redirected the braking position 180 degrees—the most common early example was the Sticht plate, but the same principle applies to today’s tube-style devices. Instead of the brake strand of rope running in the same direction as the loaded strand (the climber’s strand), the belayer had to hold the brake strand in the opposite direction.

For many years, instructors and textbooks explained how to use these new manual belay devices (MBDs) by defaulting to the hand and body positions that had become entrenched from the use of the Munter hitch and the hip belay. The most common of these was the hand-up (supinated) brake-hand position on the rope.

The stronger, more comfortable technique with MBDs is a hand-down (pronated) position with the brake hand, and newer texts and instructors often adopted this technique, in order to connect the new technology with the fundamental principles of belay. But the resulting cacophony—with belay instruction varying wildly—gave students and climbers the impression that belaying did not have any governing principles.

We climbers have our sectarian instincts, and climbers today are as likely to argue the relative merits of various belay techniques as they are to argue about the merits of sport climbing and trad climbing, alpine style and expedition style. The goal of this article is to redirect all belayers’ attention to two indisputable truths:

Belaying happens in many, many different contexts.

Belaying in every context is most effective when it is based on the three fundamental principles, which long preceded any arguments we are currently having.

THE CONTEXTS OF BELAYING

Even though we generally learn to belay in a fairly simple context (top-roping), belaying is much more diverse than what happens in an Intro to Climbing class. The most appropriate belay techniques can vary widely depending on the setting (gym, multi-pitch crag, alpine climb, etc.) and whether the climber is leading or following. Most generally, belaying happens in three different ways, using different techniques and tools for each: friction belays, counterweight belays, and direct belays.

FRICTION BELAYS

In a friction belay, the rope runs directly between the belayer and climber, and there might not be any anchor. The potential holding power of the belay is relative to the amount of friction one can generate, the strength of the belayer’s grip, and the resilience of the object providing friction.

Friction belays are most common in mountaineering (though there are other contexts where they provide efficient and prudent options). In the mountains, there usually are long stretches of terrain where a full anchor is not necessary and building and deconstructing anchors might dangerously delay the climbers.

Most commonly, the belayer will select a feature of the terrain to belay or use [their] body to create friction. The belay stance must replace the security that an anchor might have provided, whether by bracing one’s feet, belaying over the top of a ridgeline, or another method. Any terrain features used to provide friction or a stance must be carefully inspected to ensure they are solid and won’t create a rockfall hazard.

COUNTERWEIGHT BELAYS

Whether climbing single-pitch routes or belaying the leader on a multi-pitch climb, these are the most commonly used belay techniques. The climbing rope is redirected through a top anchor or a leader’s top piece of protection, and the belayer provides a counterweight, coupled with effective belay technique and tools, to hold or lower the climber or catch a fall.

Even though there are plenty of exceptions, the vast majority of American climbing happens in a single-pitch setting, on a climb that is less than 30 meters tall. The belayers and climbers generally are comparably sized, and the belayer is comfortably situated on the ground. Belaying this way provides a more social atmosphere, allowing for banter, camaraderie, and coaching. That’s why climbing gyms, climbing programs, and most casual outings gravitate toward this belay context.

However, the ease and comfort of single-pitch counterweight belays do not liberate the belayer from serious responsibilities. Thankfully, there are several different biomechanical sequences for belaying a top-rope that fall under the halo of the three fundamental principles. Each of the three techniques outlined below comes with a set of pros and cons that makes it the preferred methods of certain groups of climbers, instructors, and programs.

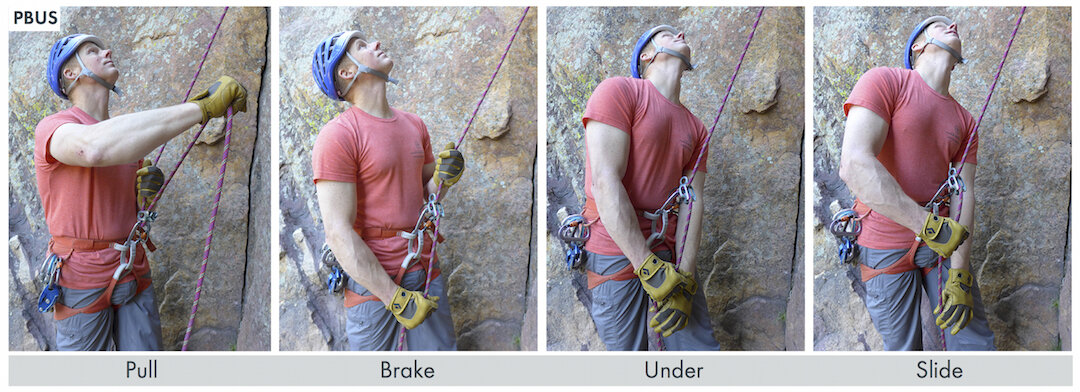

PBUS

The top-roping belay technique commonly known as PBUS resonates with climbing instructors and mentors because it emphasizes the fundamental principles so distinctly. The hand transition is securely in the braking position, and it’s hard to imagine the belayer losing control if the climber were to fall while the hand was sliding. Plus, the ergonomics of the technique keep the wrist and grip pronated.

PBUS is most effective when a top-roper is moving slowly and hanging frequently. When the climber moves quickly and proficiently, a strict adherence to this technique often causes the belay setup to collapse, which could allow the belay carabiner to cross-load. It’s also harder to move slack quickly enough to keep up with a proficient climber.

HAND OVER HAND

If the belayer alternates brake hands, [they are] able to move slack through the belay cycle more quickly than with PBUS. As long as the brake hands are alternating in the braking position, this technique abides by the fundamental principles of belay, and it is a preferred technique for experienced belayers and for top-ropers who move quickly.

Many instructors and mentors dislike this technique because it allows the belayer to keep “a” brake hand on at all times, instead of keeping “the” brake hand on at all times. As a result, this technique is usually relegated to more experienced teams.

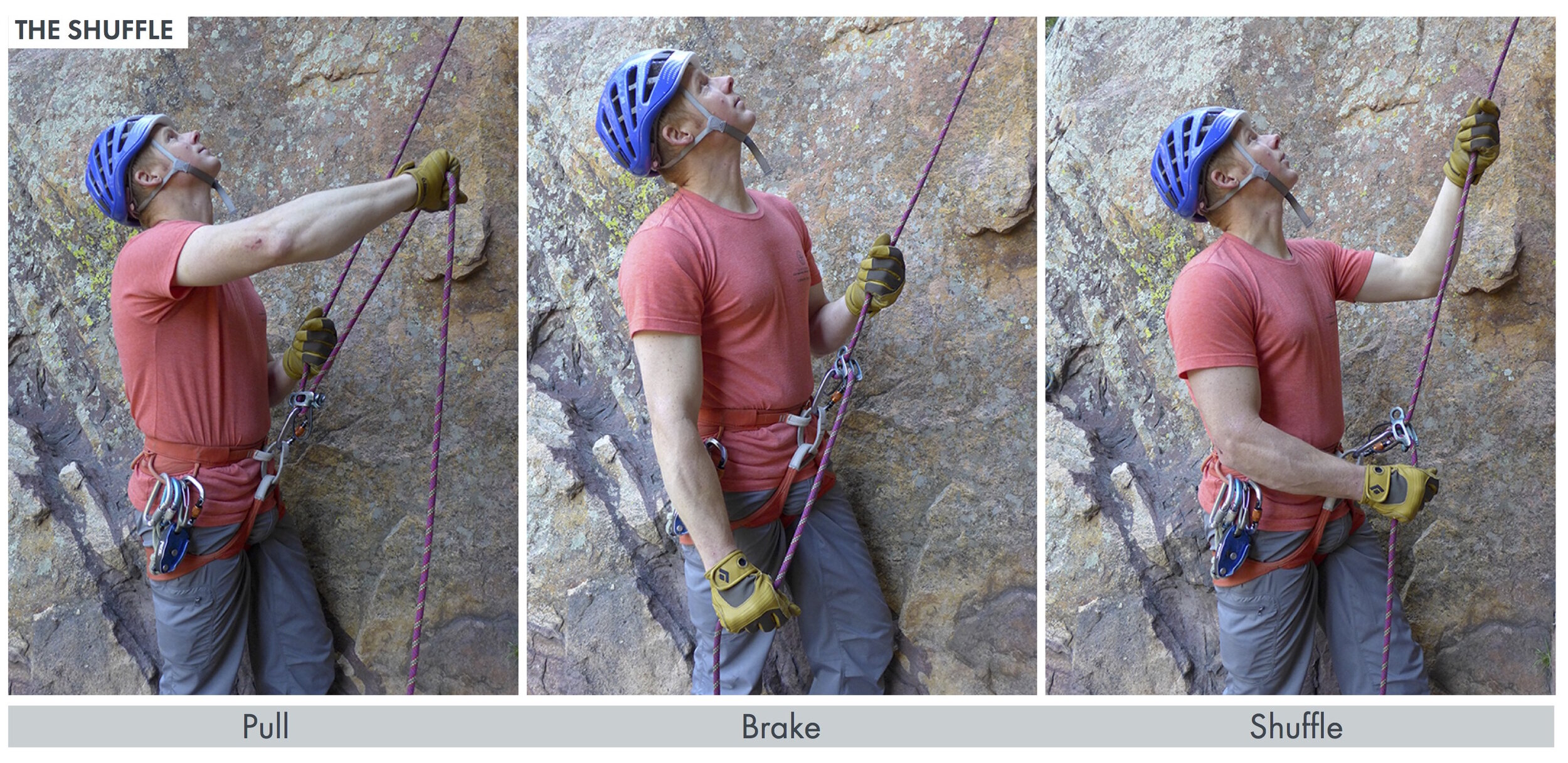

SHUFFLE

The shuffle technique is most applicable when using an assisted-braking device (ABD) to belay, but it can be used with manual devices by a very experienced belayer (read more about assisted-braking devices). It requires the belayer to have a refined sense of how to grip the rope with varying degrees of intensity, all without relinquishing the readiness to brake. A loosely gripped brake hand can shuffle along the brake strand, up or down, without letting go. A tightly gripped brake hand can be used to catch falls.

Many belayers find this technique unsettling because they are attached to the idea that a relentlessly strong grip on the brake strand is symbolic of the belayer’s commitment. With a proficient belayer, however, the shuffle technique is not only fundamentally sound, it also can be a smooth and reliable way to belay, especially with an ABD.

TOP-ROPE BELAYING IN ACTION

BELAYING A LEADER

Lead belaying involves the same fundamental counterweight arrangements as top-rope belays, but the dynamics involved in a lead fall greatly augment the forces a belayer must contend with. The loads can be severe and startling. Moreover, there is much more to effective lead belaying than simply paying out slack and catching occasional falls. The interplay of slack and tension requires quick and seamless adaptation, practiced and undistracted fine motor skills, and a situational awareness that is hard to achieve if one has never done any leading oneself. Lead belayers must master the following skills:

Setup and preparation

Correct use of the chosen belay device

Compensating for unnecessary slack

Catching falls

Unfortunately, lead belayers may only learn a portion of these skills before they are asked to perform all of them on a belay. It’s easy to imagine how a rudimentary skill set can result in frustration, accidents, or even fatalities.

SETUP AND PREPARATION

A lead belayer needs to determine the likely fall line for a climber who has clipped the first piece of protection. Standing directly beneath the first piece and then taking one step out of the fall line (roughly 10 degrees) will usually keep a falling leader from landing directly on the belayer’s head, while still keeping the belayer in position to give an effective belay.

Once the lead belayer decides where [they want] to stand, the rope should be stacked neatly on the brake-hand side, right next to the belayer’s stance. A knot in the belayer’s end of the rope (or tying in) closes the system.

USING THE BELAY DEVICE

Lead belayers will have to learn some fine motor skills to offer an effective lead belay, especially with an ABD. It takes practice.

Most of the time, the leader keeps [their] brake hand wrapped entirely around the rope, as with any other belay. The lead belayer pays out arm lengths of slack as the leader moves, and then slides the brake hand down the rope with the rope in the brake position. The mechanics are mostly identical, whether the belayer is using an MBD (such as an ATC or other tube-style device) or an ABD.

But when the leader moves quickly or pulls a lot of slack to clip protection, the belayer will have to feed slack fast, without releasing the brake hand. This is easily learned with an MBD, using a form of the shuffle technique. But with ABD devices such as the Grigri, a specific technique for each device must be learned and practiced. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions and warnings. (Most have produced instructional online videos explaining the appropriate technique.) No matter which device you use, keep the fundamental principles of belaying in mind. Most importantly, your brake hand must stay on the rope as you feed slack.

COMPENSATING

Lead belaying also involves a subtle exchange of giving and taking rope called compensating. When a leader makes a long clip, there is a moment where the rope is actually clipped above the leader’s head, and [they are] effectively on a short top-rope. As a result the belayer needs to make a seamless transition between giving slack, taking in slack, and giving slack again. The most extreme version of compensating happens when the leader downclimbs from a clip to a rest and then reascends to the high point.

CATCHING FALLS

The most important part of catching a fall is stopping a leader from hitting the ground or a ledge—or abruptly slamming into the wall. On overhanging climbs, a leader is less likely to impact objects, so longer falls are acceptable. But on vertical or low-angled climbs, the same length of fall could easily cause the leader to impact features along the fall line.

The lead belayer must be constantly prepared to mitigate the fall consequence as much as [they] can, and a key part of this is maintaining the appropriate amount of slack and movement in the system. While belaying a leader on an overhang, the belayer might feel free to let the momentum of the counterweight lift [them] off the ground. This is the coveted “soft catch” that so many leaders seem to think is essential.

But when a fall is more consequential—when it might result in ledge impact or a ground fall—an astute belayer may “fight” the fall, sometimes even taking in slack and bracing to increase the counterweight effect.

It takes time and effort to learn this distinction, because every climb is a little different. One of the most important ways to learn lead belaying is to lead climb. An experienced leader will better understand the issues facing other lead climbers and will know what it feels like to have a belayer do [their] job perfectly.

LEAD BELAYING IN ACTION

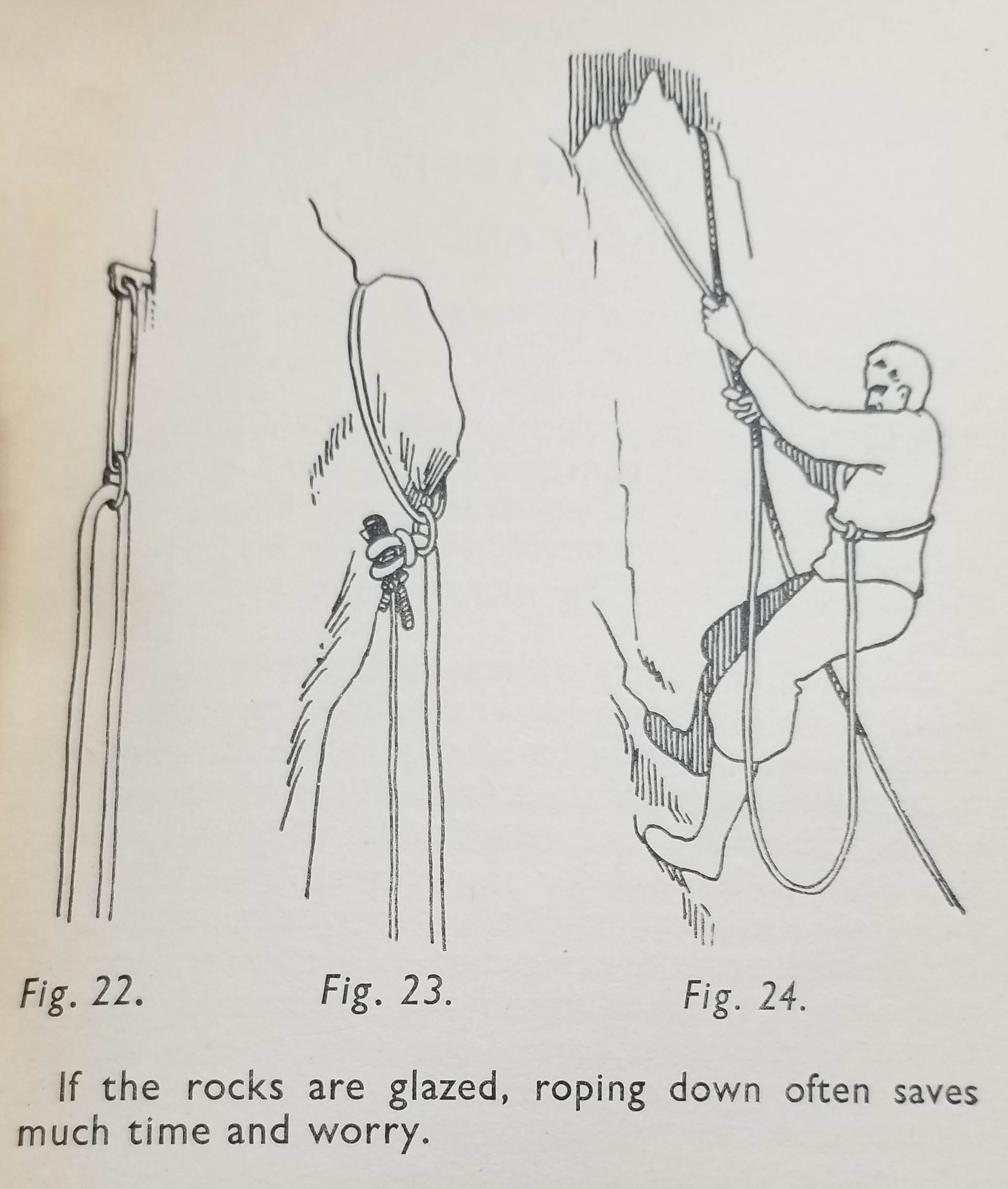

DIRECT BELAYS

Direct belays connect the belay system directly to an anchor. As a result, the anchor must be fundamentally sound. That is to say, it has redundant construction, distributes loads intelligently to all the components, limits potential shock-loading if a single component were to fail, and is adequately strong. The anchor must easily sustain all the potential loads applied to it, plus a healthy margin of error. Its integrity should not be in question. Read more about anchors here or here.

Direct belays are the most prudent way to belay a second from the top of a rock or ice pitch where falls are likely and consequential. (That would include all fifth-class rock terrain and almost every ice climb at any grade.) They do not trap the belayer in a counterweight arrangement, allowing the belayer to manage the rope and multi-task. Because the belayer is attached to the anchor separately, the belayer can affect assistance techniques to help a climber move up if needed. Direct belays also put less force on an anchor than counterweight belays do (which shouldn’t matter, really, because the anchor should be bombproof). Lastly, they are particularly advantageous when belaying more than one person simultaneously.

Whether the belayer is using a Munter hitch, an MBD, or an ABD in a direct belay, the fundamentals apply: The brake hand is always on the rope, hand transitions occur in the braking position, and the limbs are positioned in ways that are comfortable and sustainable. Direct belays should confer all of the climber’s weight to the anchor, so it is easy to imagine a few different hand positions that take advantage of the belayer’s natural strength.Lowering is a completely different story with direct belays. As articles in Accidents will attest, lowering will usually require the belayer to disable or reduce a device’s autoblocking or braking function. As a result, the belayer should redirect the rope through the anchor and use a friction hitch or backup belay whenever [they are] lowering from a direct belay.

COMMON MISTAKES

FINAL THOUGHTS

As we can see, there are so many variables to belaying that it can be counterproductive to say there is only one “right” technique. The appropriate belay method for each pitch depends on the terrain, the style and difficulty of climbing, the relative experience and weight of the climber and belayer, and the tools available. The “right” technique is the one that’s appropriate for each context, as long as it adheres to the fundamental principles of keeping your brake hand on the rope, sliding your hand only when the rope is in the braking position, and positioning your hands and body according to their natural strength.

Keep exploring belaying by watching our Know the Ropes videos here or checking out this slideshow. If you teach belaying or just want to take a deep dive, see the AAC’s own Gold Standard curriculum.

Find more information on a variety of topics, including “Climber Communication,” by checking out our complete Know the Ropes collection.