An Upcoming Film from Jon Glassberg, Sophi Rutherford, and the Pull Focus Grant

In Dear Mother, climber and transracial Asian-American, Cody Kaemmerlen, searches for connection with his birth parents after a near-death fall leaves him shaken and grasping for answers.

Synopsis

Cody Kaemmerlan is a climber adopted out of South Korea in 1984, into rural Tillamook, Oregon. He was raised by a loving family, and thrived in his small town, not fully comprehending what it was like to be a person of color in a white world. After reaching out to the adoption agency, he was left with an email stating his birth mother had no interest in meeting her son. He struggled in adulthood, as he started to experience adversity which produced a cycle of anger, divorce, car accident, and finally a near-death free-soloing fall which became a catalyst for change.

A few years later, the agency reached out with an apology about a file mix-up, stating his birth mother and father would love to meet. Soon after, he begins to process his adoption and identity with the help of the climbing community and close friends.

Follow Cody to South Korea on his mission to meet his mother and father, in hopes of finding resolution and inner peace.

ABOUT The Directors:

Louder Than 11 is a media production company and creative agency based in Boulder, Colorado, run by Jon and Jess Glassberg. LT11 delivers authentic narratives through their work with top-level brands, professional athletes, and other creatives in the Outdoor Industry. Louder Than Eleven is made up of passionate filmmakers, photographers, and professionals who tell great stories through adventure media.

In Association With:

ABOUT THE PULL FOCUS GRANT:

Climbers build their lives around adventure in the outdoors. Climb United is committed to being adventurous in our pursuit of others’ perspectives. We know how important climbing media is in shaping climbing culture. We also know that the stories that have been told have highlighted those in power. We want to remove barriers that underrepresented communities continue to be challenged with when accessing the outdoor media and production industry and to support the progression of a talented filmmaker’s career.

Introducing Pull Focus: a storytelling grant that provides BIPOC, LGBTQ+ individuals, and people with both seen and unseen disabilities the funds and mentorship support to create and share stories that reflect their communities. The Pull Focus Grant is made possible by Mountain Hardwear!

Dear Mother was assistant directed by the recipient of the Pull Focus Grant, Sophi Rutherford. Read about Sophi’s artistic philosophy and why she resonated with Cody’s story in this profile of Sophi as an emerging filmmaker.

CREDITS:

A Louder Than Eleven Production

Presented by American Alpine Club

In Association With Mountain Hardwear

With Support From A-Lodge & Pro Photo Rental

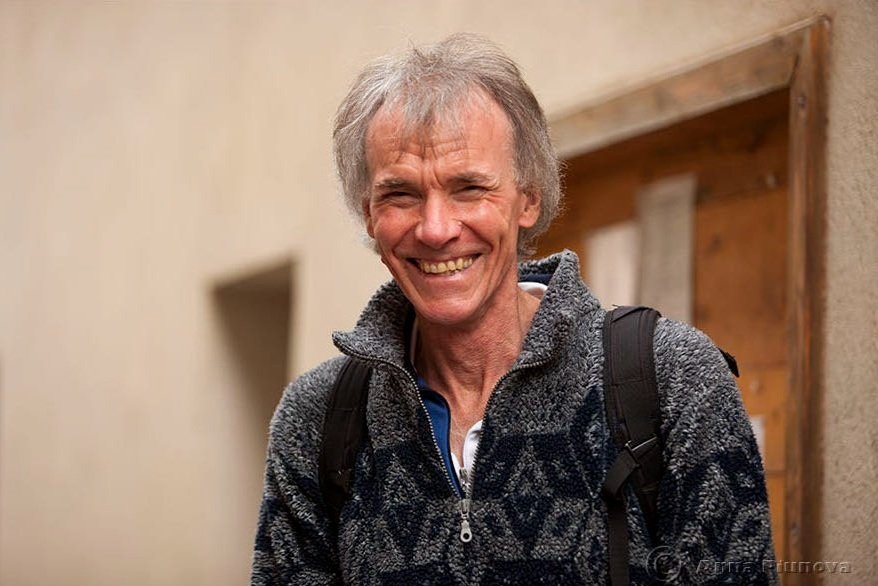

Directed by Jon Glassberg

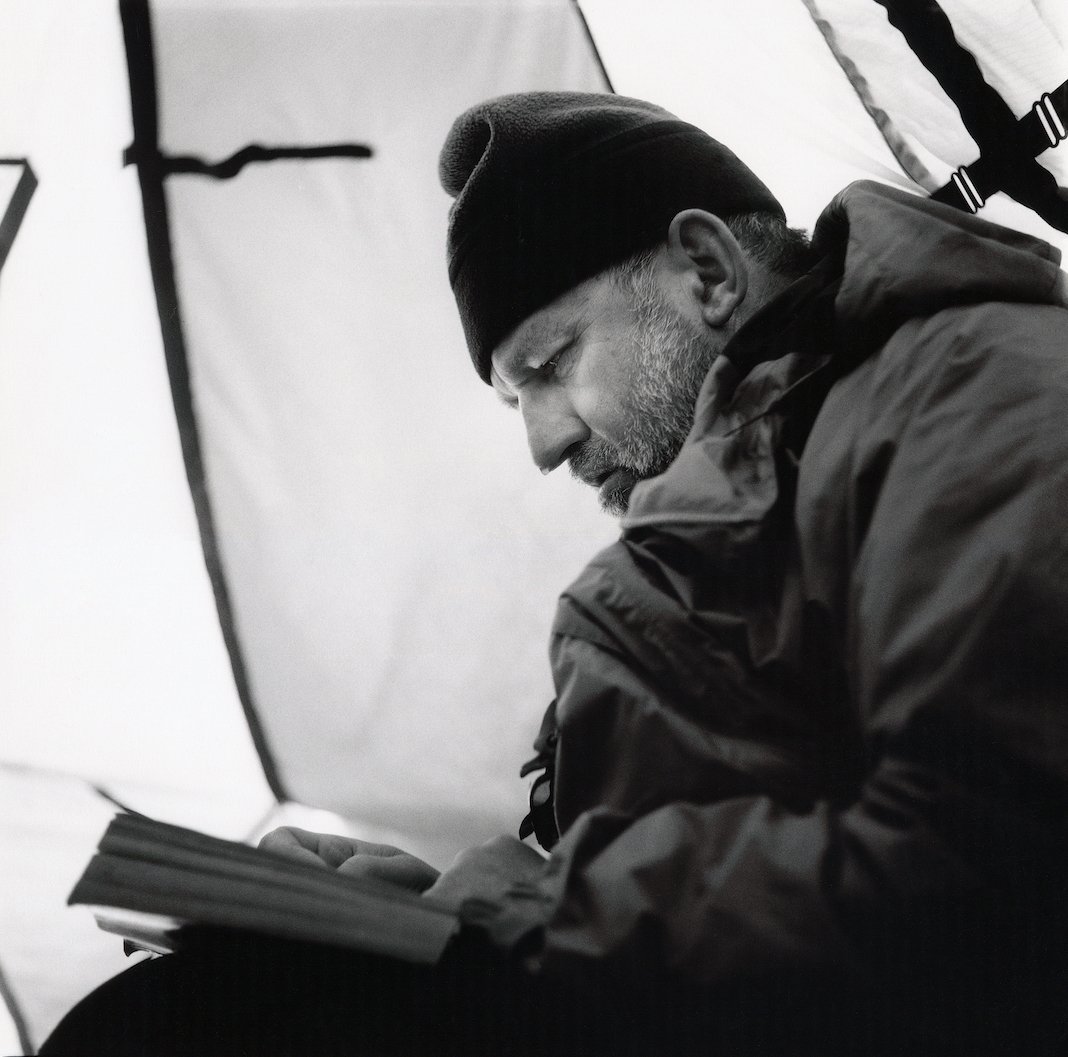

Starring Cody Kaemmerlen

Birth Parents Nam Family

Featuring Janet Kaemmerlen, Mike Kaemmerlen, Nina Williams, Suah Yu, Peter Clotfelter-Quenelle, Hoseok Lee

Assistant Director Sophi Rutherford

Written by Jon Glassberg, Jessica Glassberg

Edited by Jon Glassberg

Assistant Edit Saraphina Redalieu

Video by Jon Glassberg, Jessica Glassberg, Sophi Rutherford, Cody Kaemmerlen

Photography Sophi Rutherford, Jessica Glassberg

Archival Material Provided by Cody Kaemmerlen, Kaemmerlen Family, Joey Maloney

Voice Over Mei Ratz