In a typical single-pitch climbing scenario, where the pitch length is less than half the available rope, the ground closes the system by default, meaning your partner is going to make it back to the ground before the belayer gets to the end of the rope, so closing the system is unnecessary. The problem comes when the anchor is near or above the midpoint of the typical rope. This is increasingly common as new routes are established with anchors above 30 meters (half the typical modern rope length). For some climbs, a 70-meter rope is now mandatory to lower safely. Before trying an unfamiliar single-pitch route, read the guidebook carefully, ask nearby climbers, and/or research the climb online to be sure it doesn’t require a 70-meter rope to descend safely. When in doubt, bring a longer rope or trail a second rope.

Another scenario frequently leading to single-pitch lowering accidents is a climb where the difficulties begin after scrambling five or ten feet to a high starting ledge. The anchors at the top of such routes may be set in such a way that there is plenty of rope to lower the climber back to the ledge, but not all the way to the ground. Or the belayer may need to be positioned on the starting ledge in order to have enough rope to lower the climber safely. Again, do your homework, ask other climbers, and always watch the end of the rope as you’re lowering a partner.

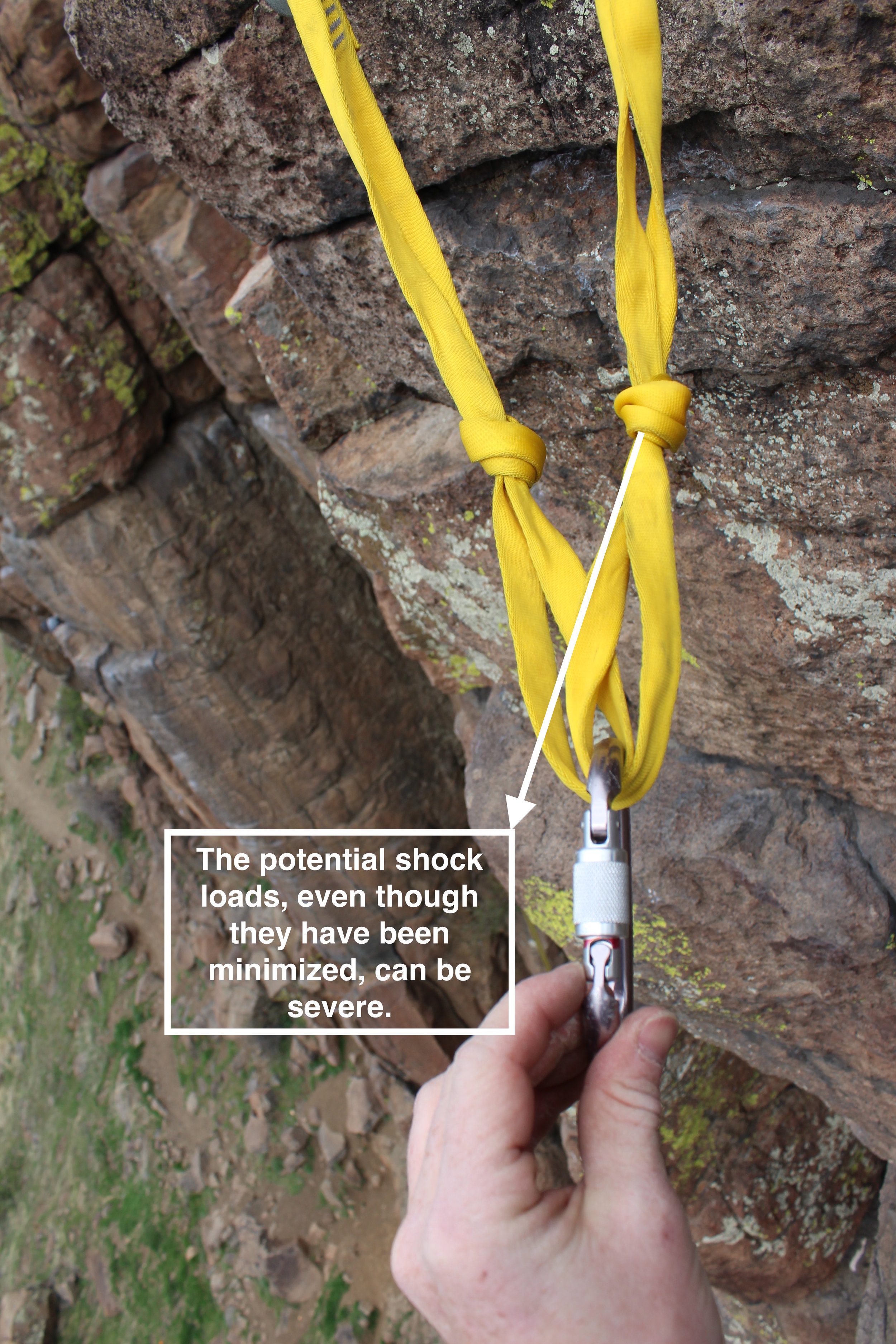

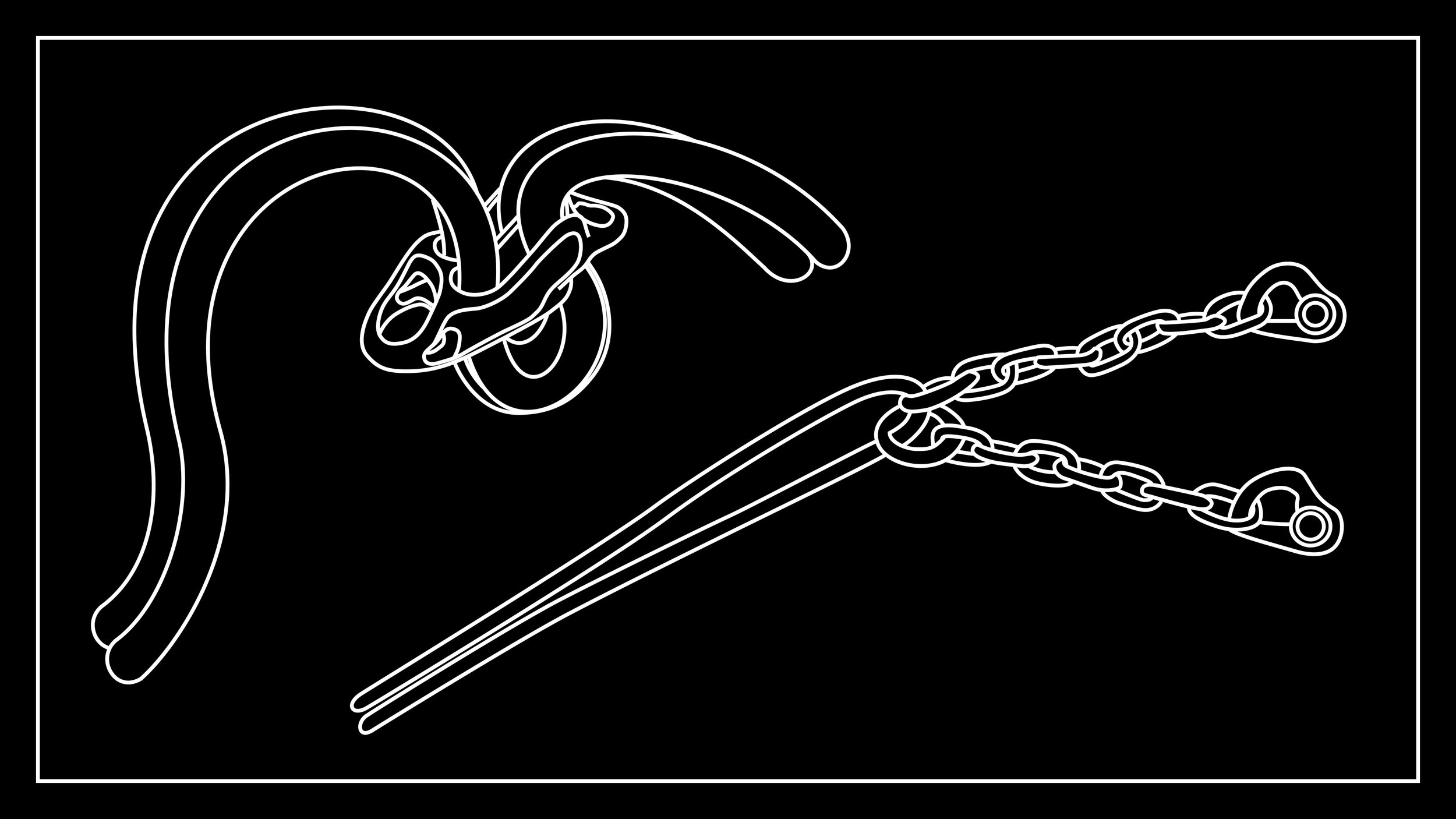

If there is any doubt about the length of the rope being adequate to lower a climber safely, tie a bulky stopper knot in the free end so it cannot slip through the belay device. (The triple overhand knot is a good choice; see Figure 1.) Better yet, the belayer can tie into the free end, thus closing the system.

As you belay a lead climber on a long pitch, keep a close eye out for the middle mark so you’re aware of whether there is enough rope to lower the climber. Once the middle of the rope passes through your belay device, you and the climber need to be on high alert. Rope stretch may provide a little extra room for the climber to be safely lowered to the ground, but in such cases the system should always be closed as discussed above. When in doubt, the climber should call for another rope and rappel with two ropes.

As the climber lowers, it’s natural to keep an eye on her, but as the belayer you should also be watching the pile of free rope on the ground. Once there is less than 10 or 15 feet remaining, make a contingency plan for safely completing the lower. For example, will the climber have to stop on a ledge and downclimb? Will you need to move closer to the start of the route? Never let the last bit of rope slip through the device if the climber is still lowering, even if she is only a foot or two off the ground—the sudden release of tension can lead to a free fall and tumble.

When lowering in the multi-pitch environment, the belay system must be consciously closed by having the non-load end of the rope tied to the belayer, the anchor, or something else to prevent it from passing through the belay device. In a multi-pitch rappelling scenario we close the system by knotting the ends of the rappel ropes, making it impossible to rappel off the ends.

Miscommunication

The three key problems with communication between climber and belayer are 1) environmental, 2) unclear understanding of command language, and 3) unclear understanding of the intentions of the belayer and climber.

Environmental problems include the climber and belayer being unable to see each other because of the configuration of the route and/or the distance between the two; weather conditions such as wind, snow, or rain; and extraneous noises, such as a river, traffic, or other climbers shouting commands or chatting nearby.

In popular climbing areas with many parties on routes near each other, climbers sometimes mistake a command from a nearby party as coming from their partner. It’s always a good practice to use each other’s names with key commands: “Off belay, Fred!” or “Take, Jane!” When one climber is at the top of a single-pitch climb and rigging the anchor for a lower-off, top-rope, or rappel, it can sometimes be helpful for the belayer to step back temporarily so he can see his partner at the anchor and improve communication. When the climber is ready to lower, the belayer can move back to the base of the climb to be ideally positioned for the lower.

Especially with a new or unfamiliar partner, it’s essential to agree on the terms you’ll be using to communicate when one climber reaches the anchor. What do you mean by “take” or “off” or “got me?” Avoid vague language like “I’m good” or “OK.” Agree on simple, clear terms and use them consistently. One common misunderstanding seems to be the result of the similar sounds of “slack” and “take.” When top-roping, consider using the traditional term “up rope” instead of “take” for more tension in the rope, as the former won’t be confused with “slack.”

Before starting up any single-pitch climb, it’s critical that belayer and climber each understand what the other person will do when the climber reaches the anchor: Will the climber lower off, and if so what language will she use to communicate with the belayer? Or, will she clip directly to the anchor, go off belay, and rappel down the route? Many accidents have resulted when the belayer assumed the climber was going to rappel instead of lower, or the belayer forgot that the climber planned to lower, or he misunderstood a command (“off” or “safe” or “I’m in direct”) as an intention to rappel. Before taking the climber off belay, the belayer must be certain that this is the climber’s intention. If you have agreed that the climber will rappel, wait for the climber to yell “off belay,” and then respond “belay off,” and only then remove the rope from your device.

When you reach the anchor at the top of a climb, don’t just clip in, shout “take,” and lean back. Make sure to hear a response from the belayer indicating that he has you on belay and is ready to lower. If you can’t see the belayer, sometimes it is possible to extend your anchor connection or lower yourself a little, holding onto the “up” rope, until you can get into position to make visual contact with the belayer and assure you’re still on belay.

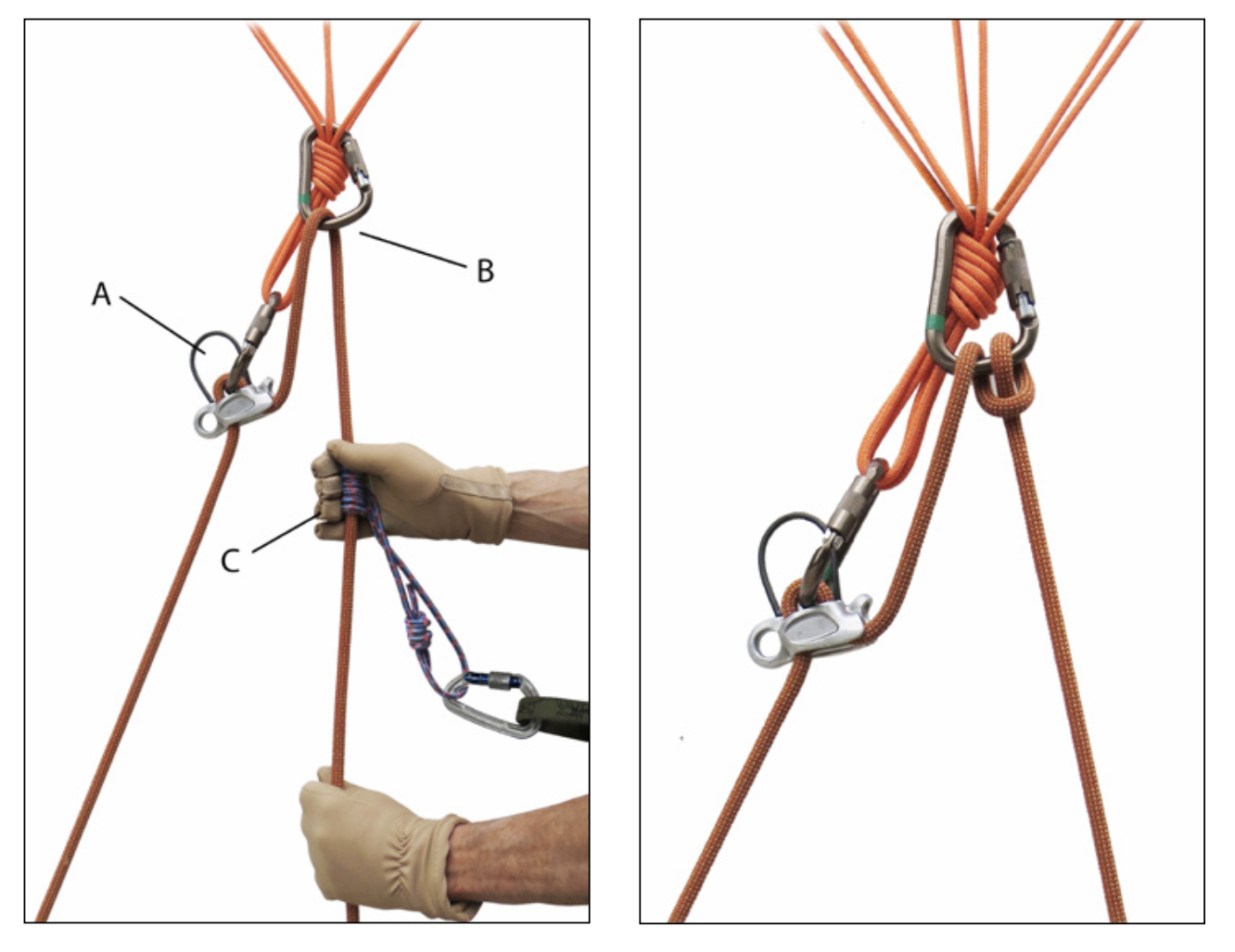

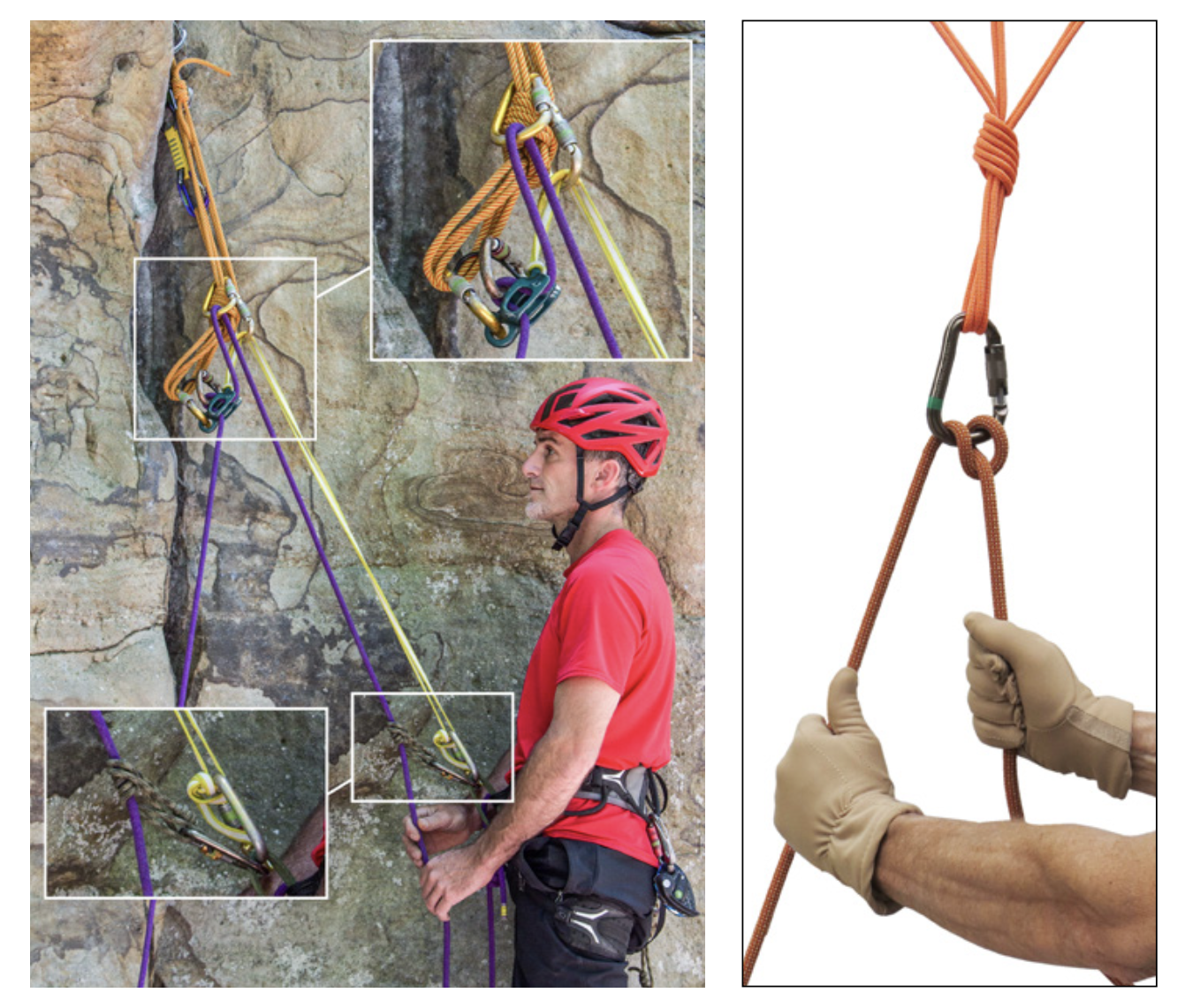

A consideration when lowering someone from above is that the belayer and climber become farther apart during the lowering process, and this may compromise communication. To mitigate this potential problem, I like to position myself where I can see, and hopefully hear, the climber being lowered from start to finish. In some terrain this requires extending the anchor’s master point.

Belay System Errors

A common cause of lowering accidents is belayer errors, especially when the belayer is inexperienced, inattentive, or unfamiliar with the operation of a particular type of device. Make sure your belayer—or any belayer you observe— knows what he’s doing and pays attention until his climber is safely back on the ground or at an anchor. Don’t accept or ignore shoddy belaying!

On single-pitch routes, two things that may cause problems are belayers positioned too far back from the base of the climb—and thus getting pulled off balance and possibly losing control when the climber weights the rope—as well as using an unfamiliar device. Switching between tube-style devices, such as an ATC, and assisted-braking devices like the Grigri can cause inexperienced belayers to mishandle the device. Beware of loaning your device to a belayer unless you are confident that he is well-trained in its use.

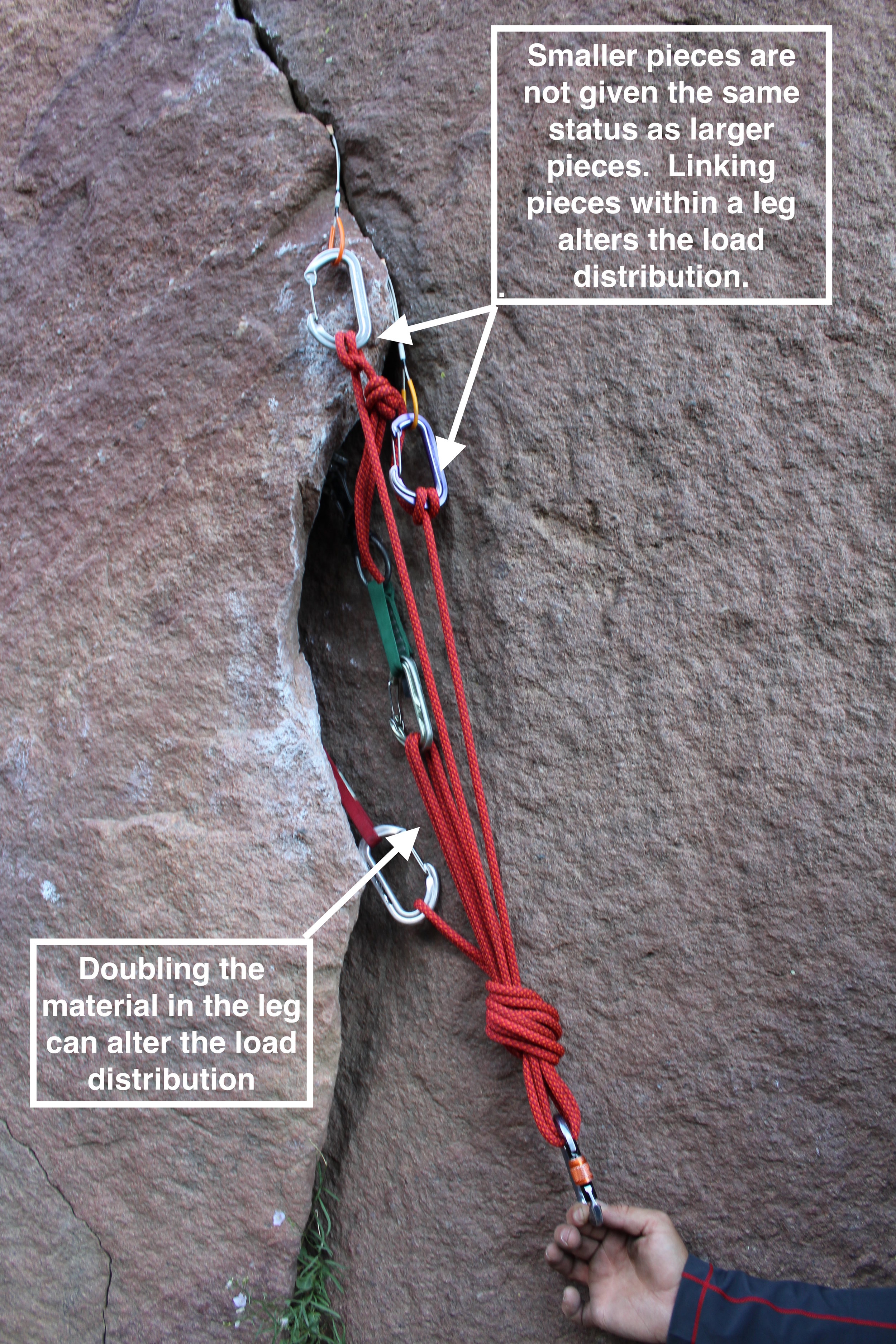

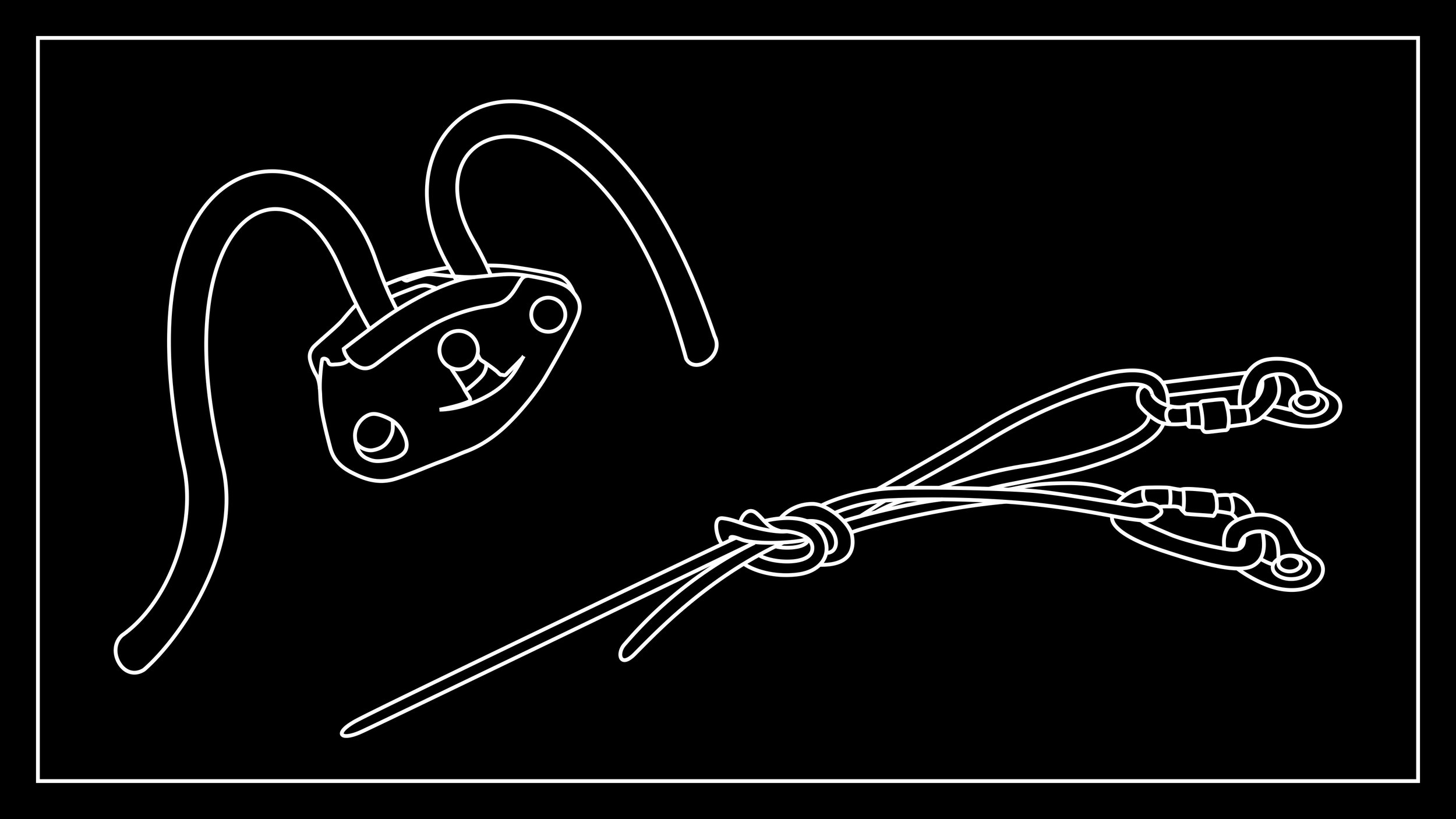

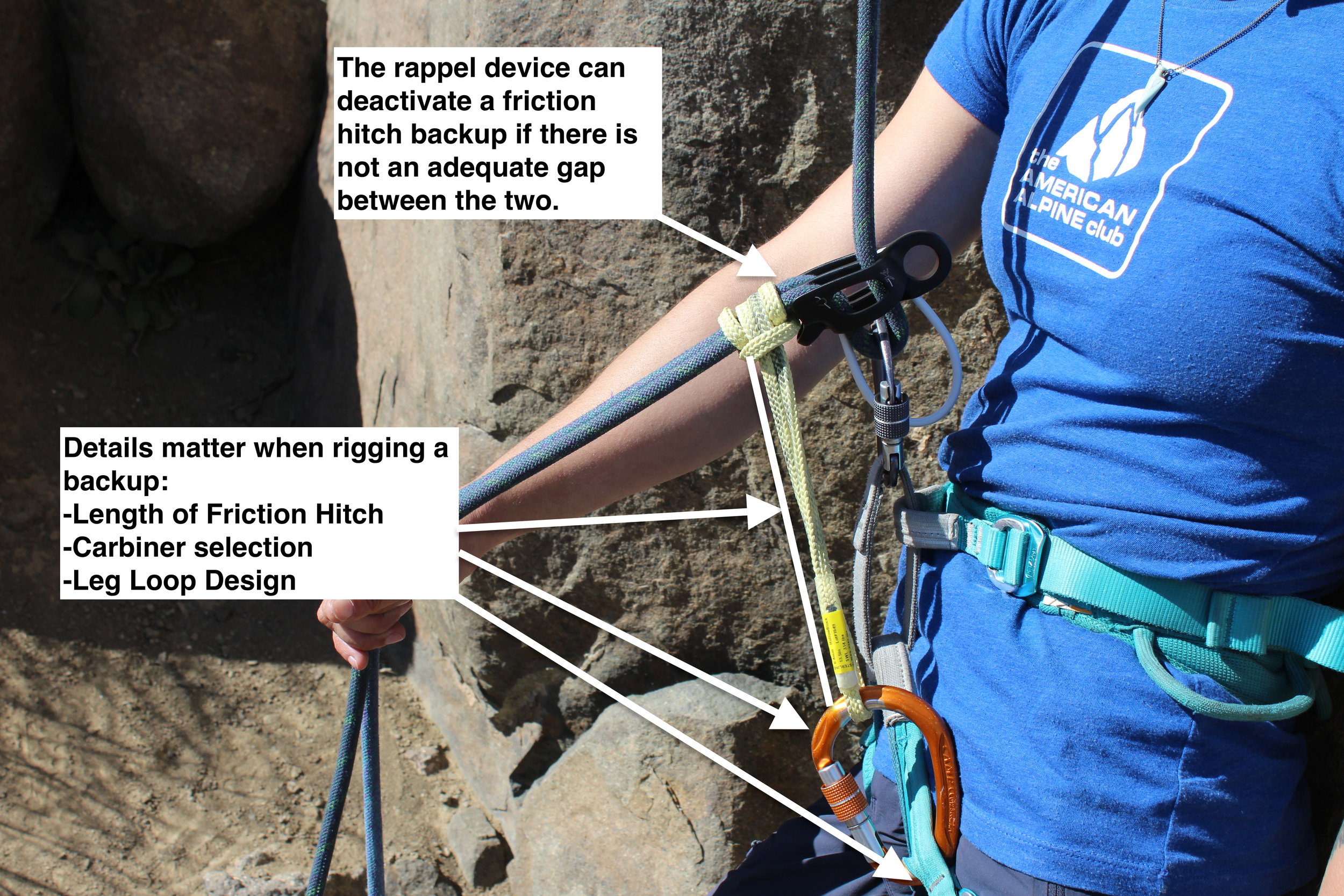

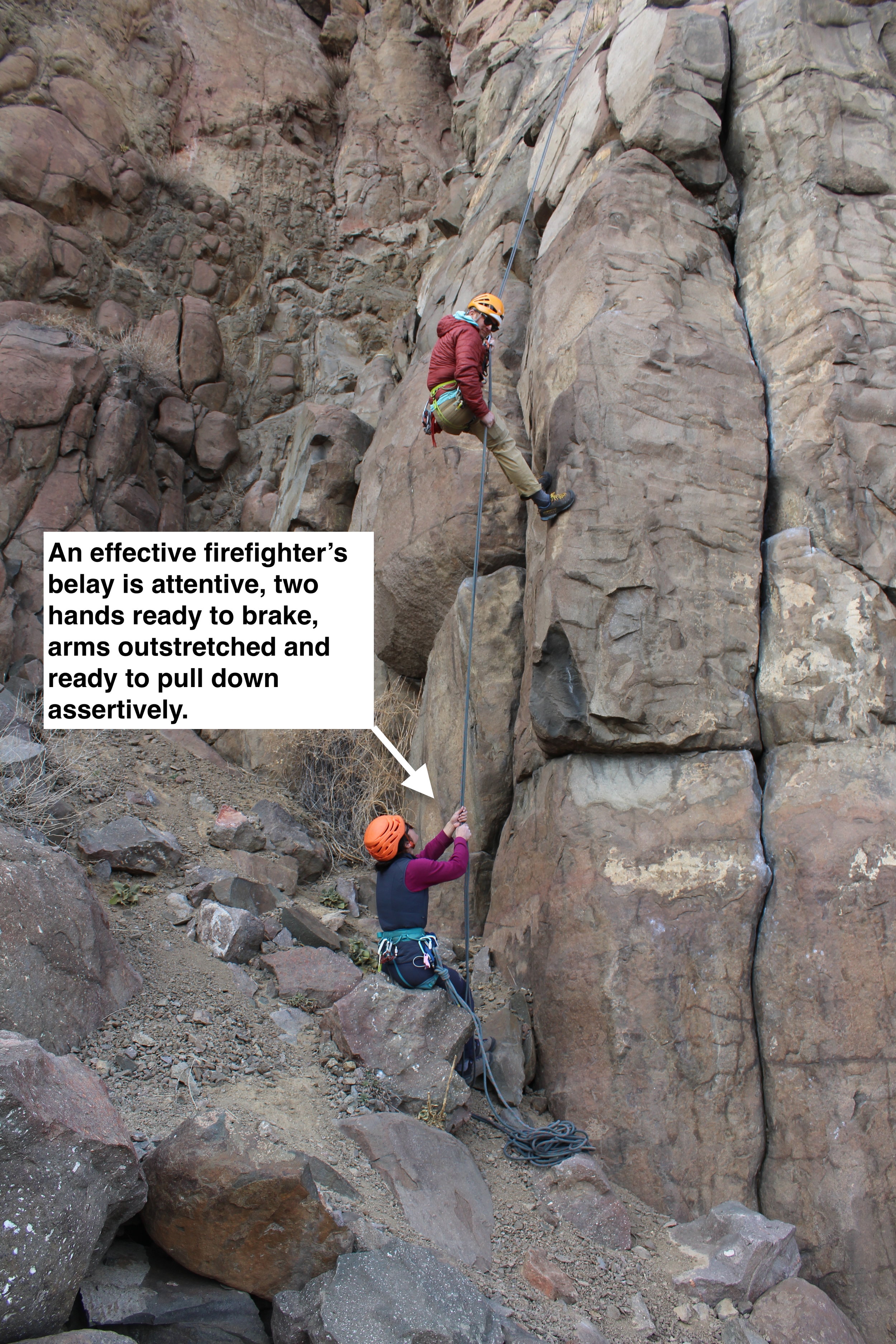

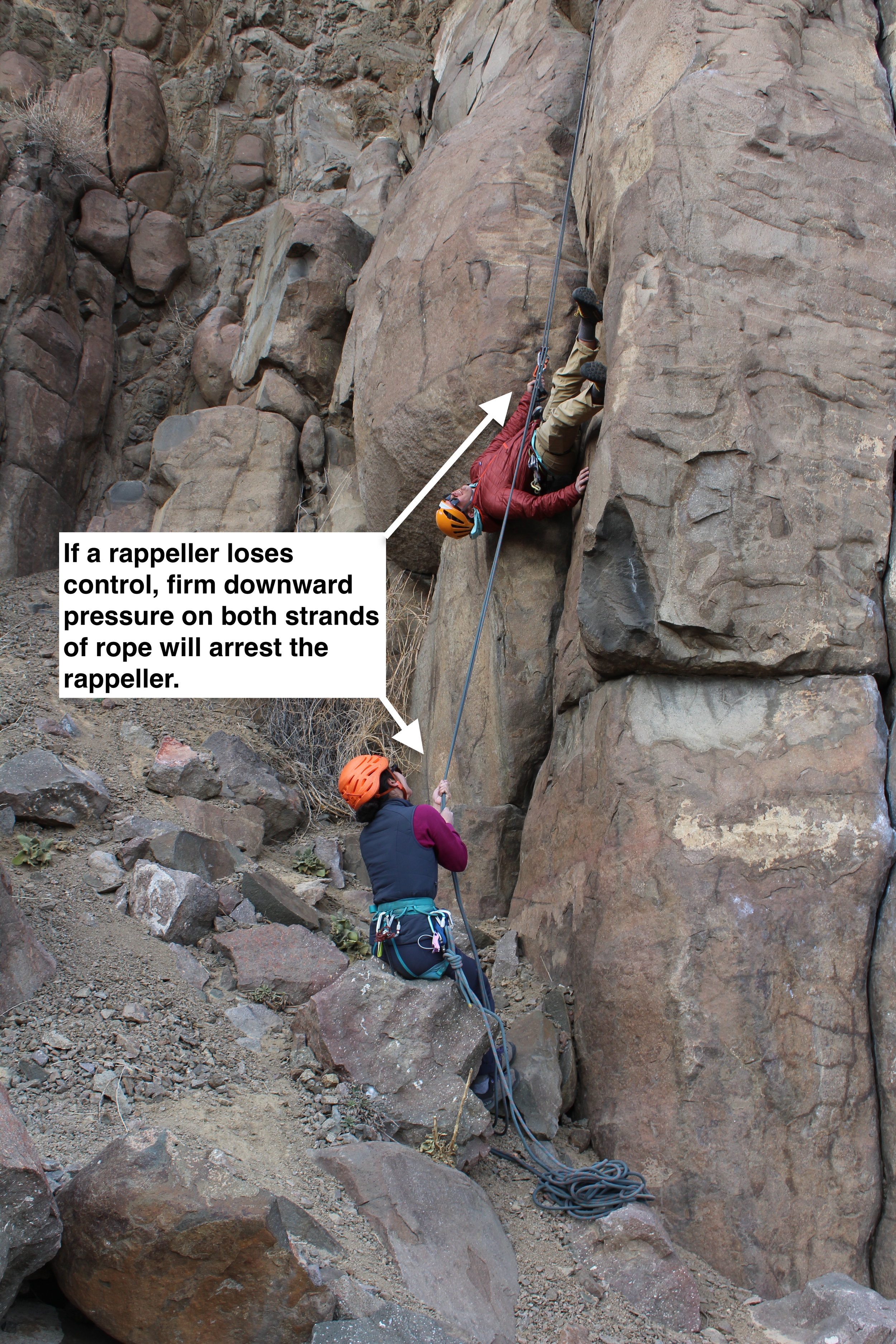

What is the appropriate lowering brake for lowering your partner? It’s one that provides adequate friction to control their descent over very specific terrain. In some alpine terrain situations, the redirected hip belay may be totally sufficient for a short, moderate-angle step with high friction. Conversely, lowering directly off an equalized multi-point anchor with a backup may be required in steeper terrain (see Figure 2).