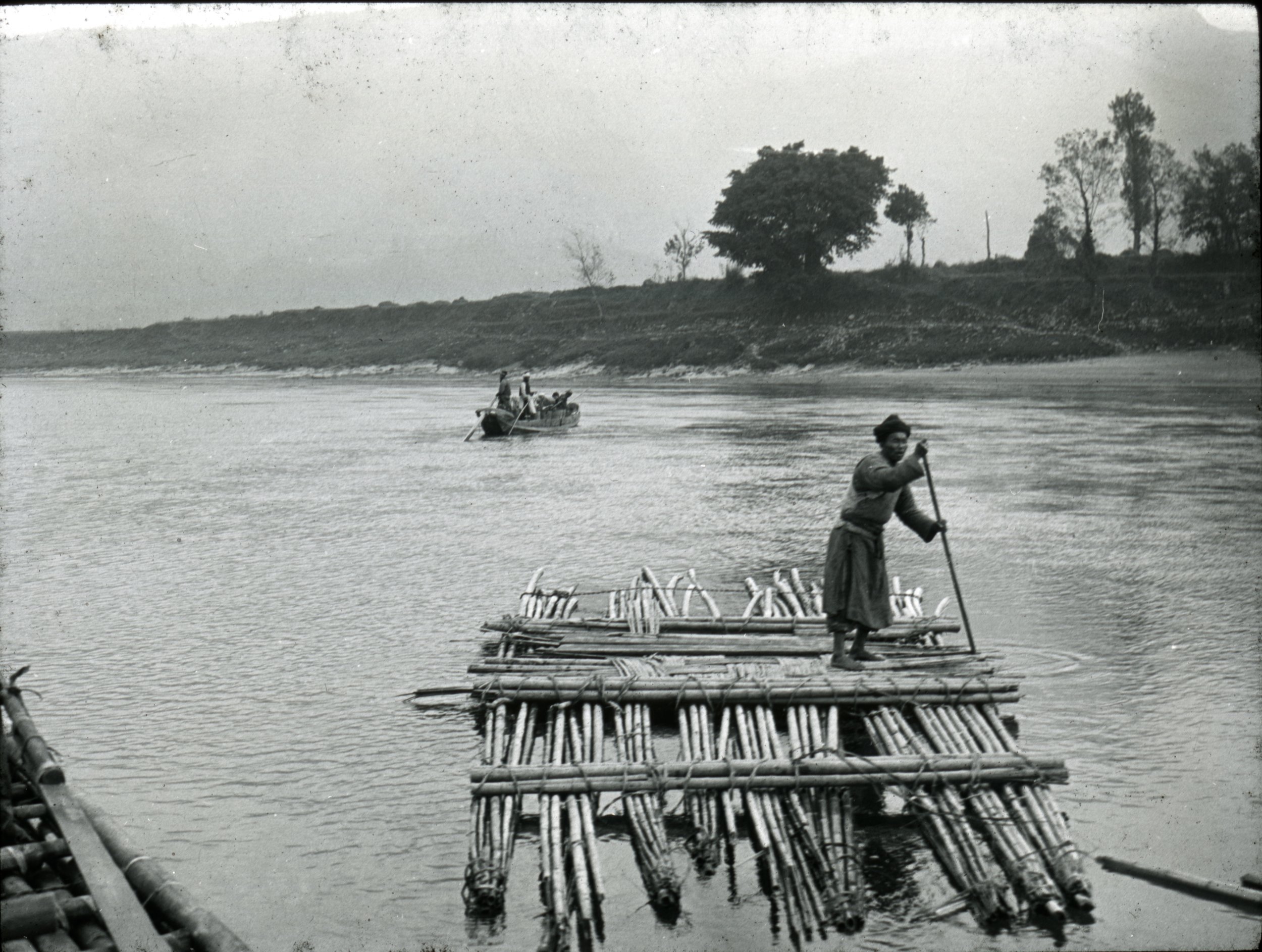

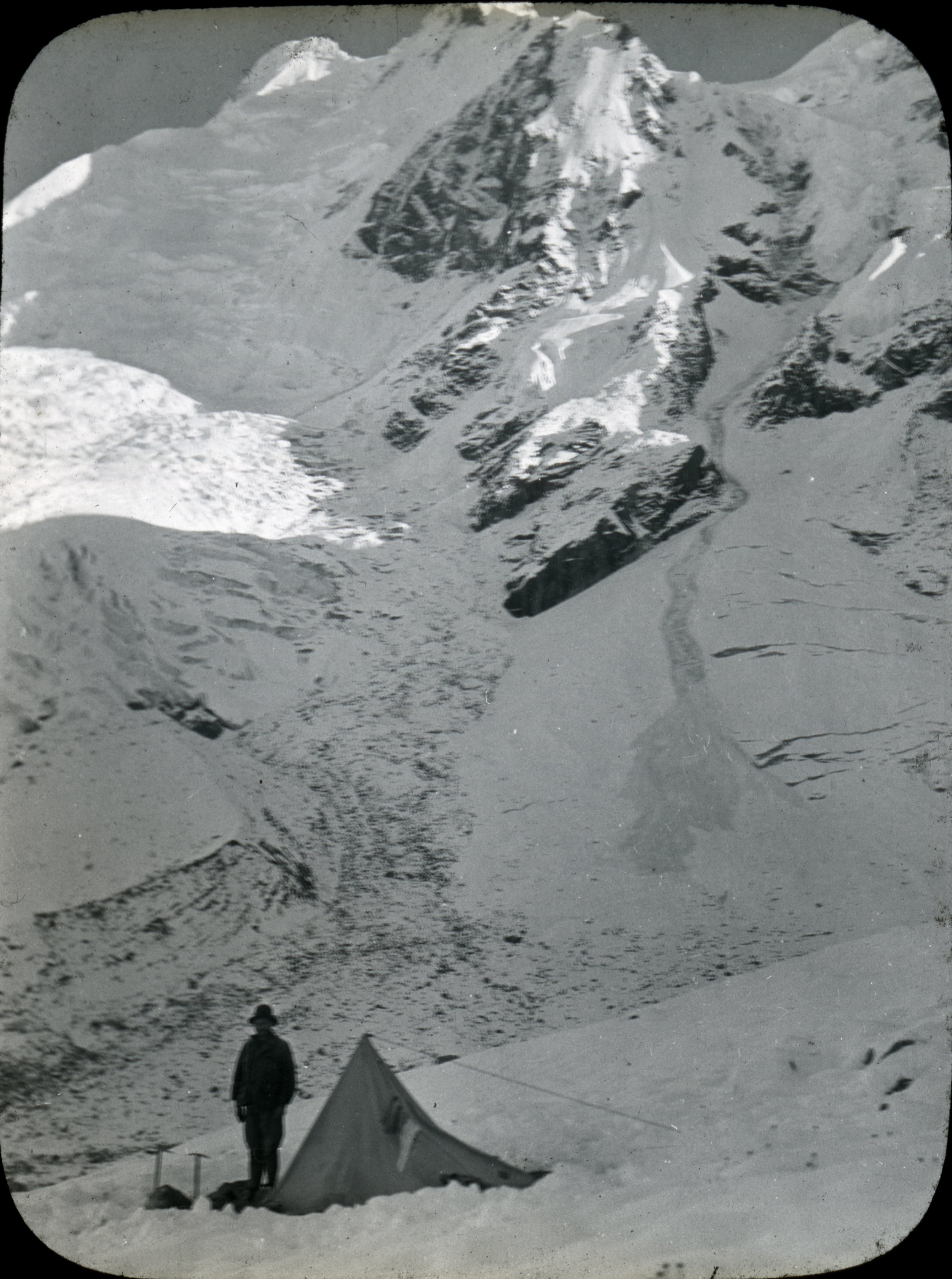

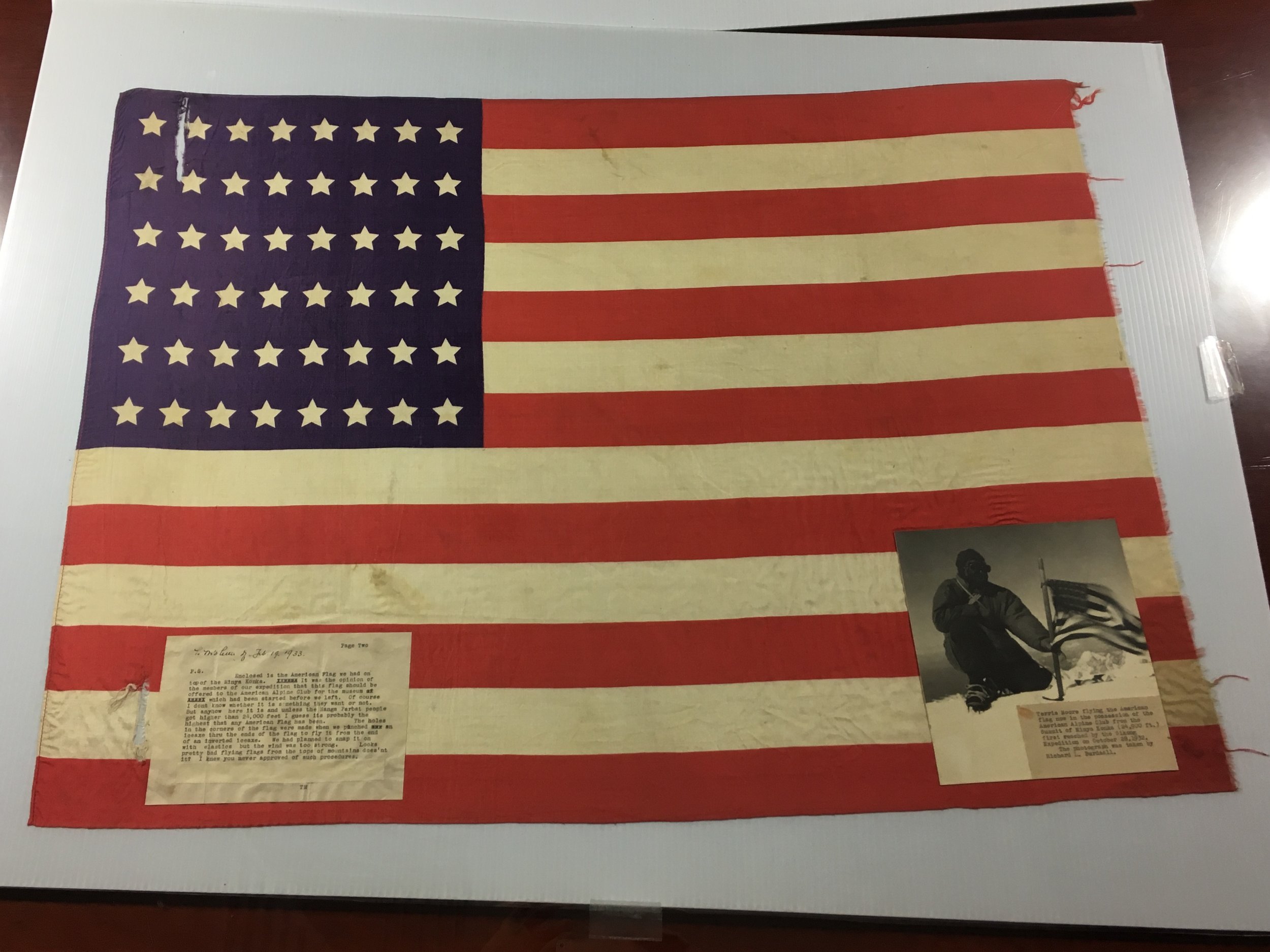

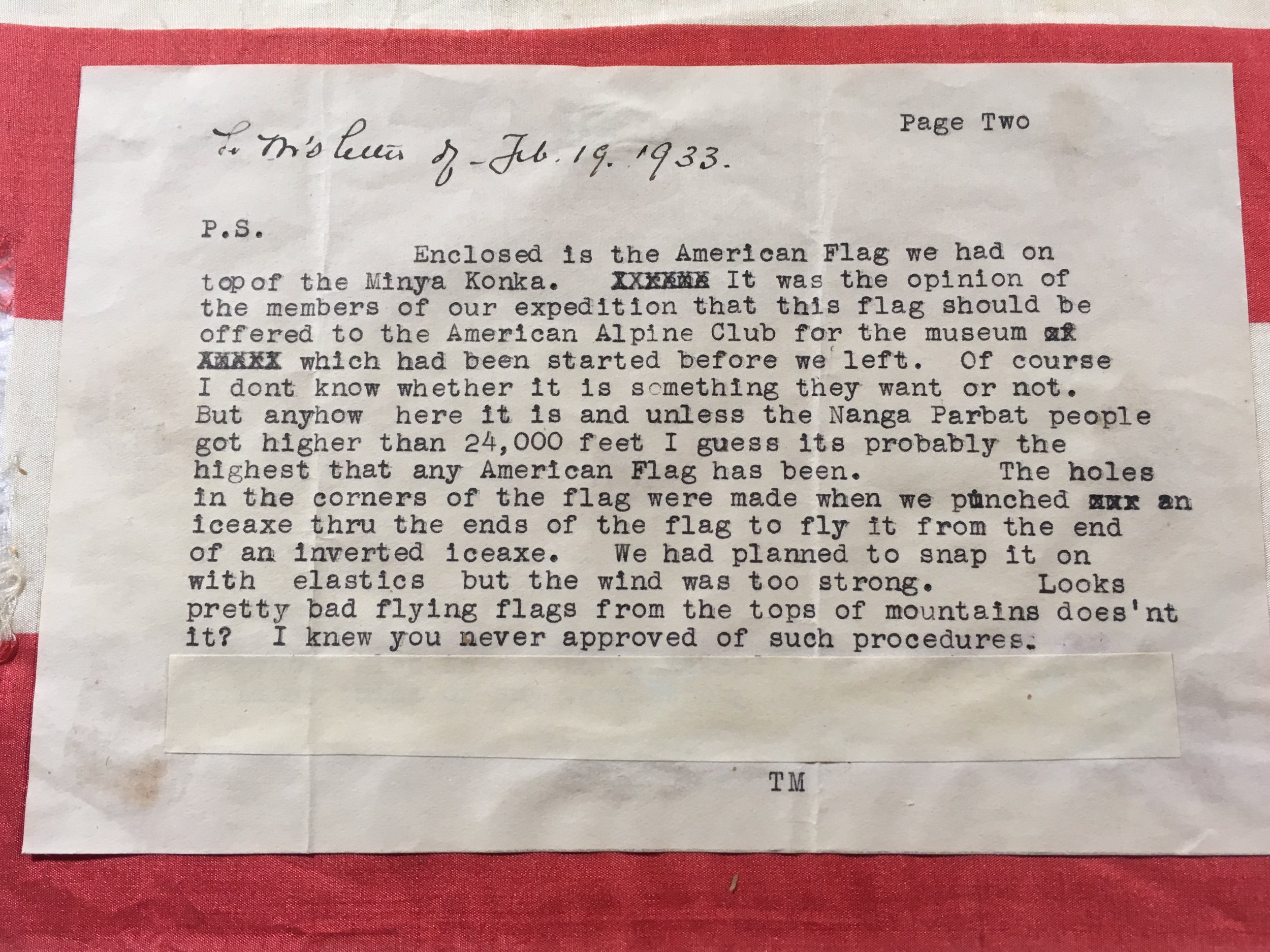

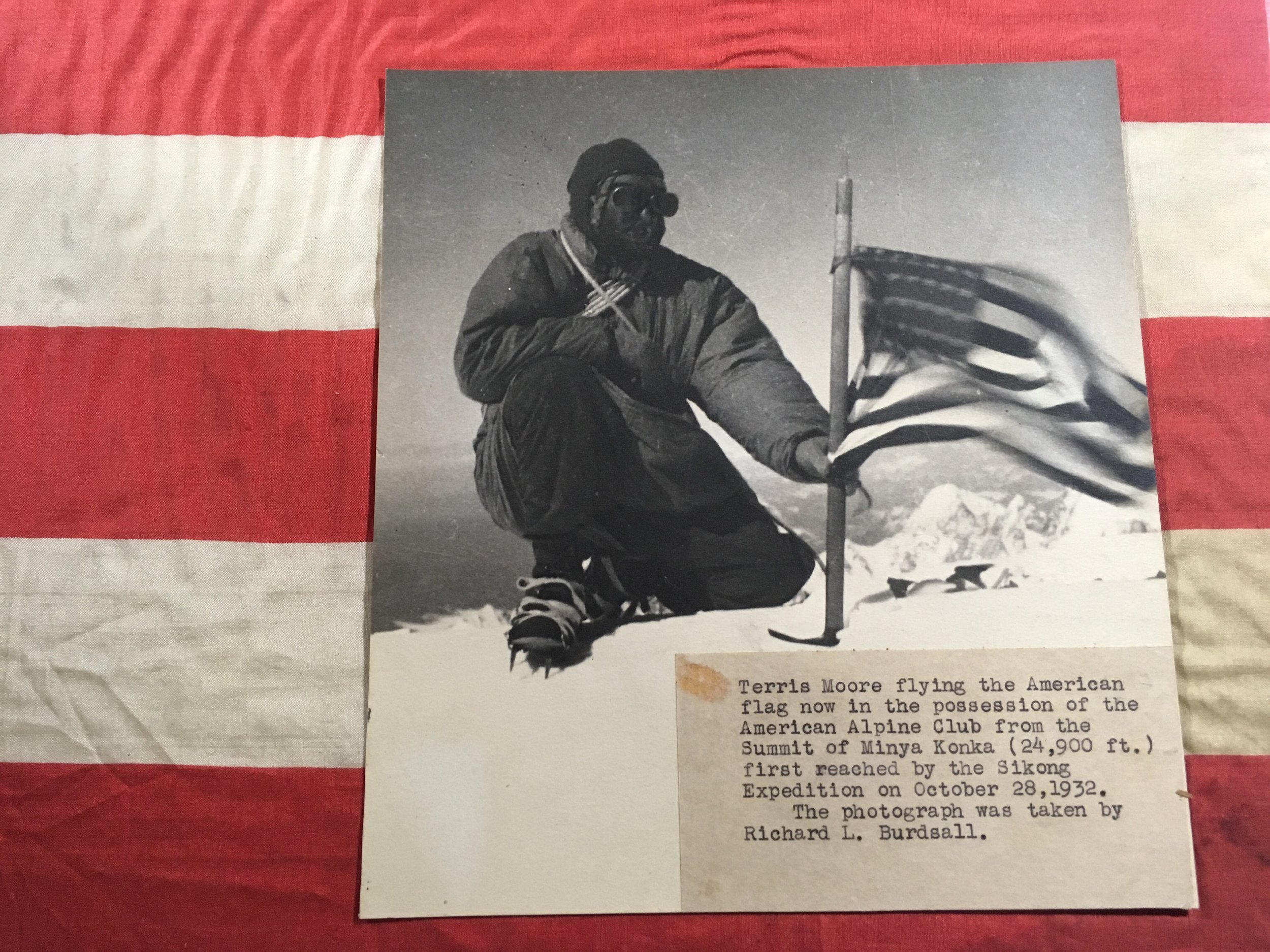

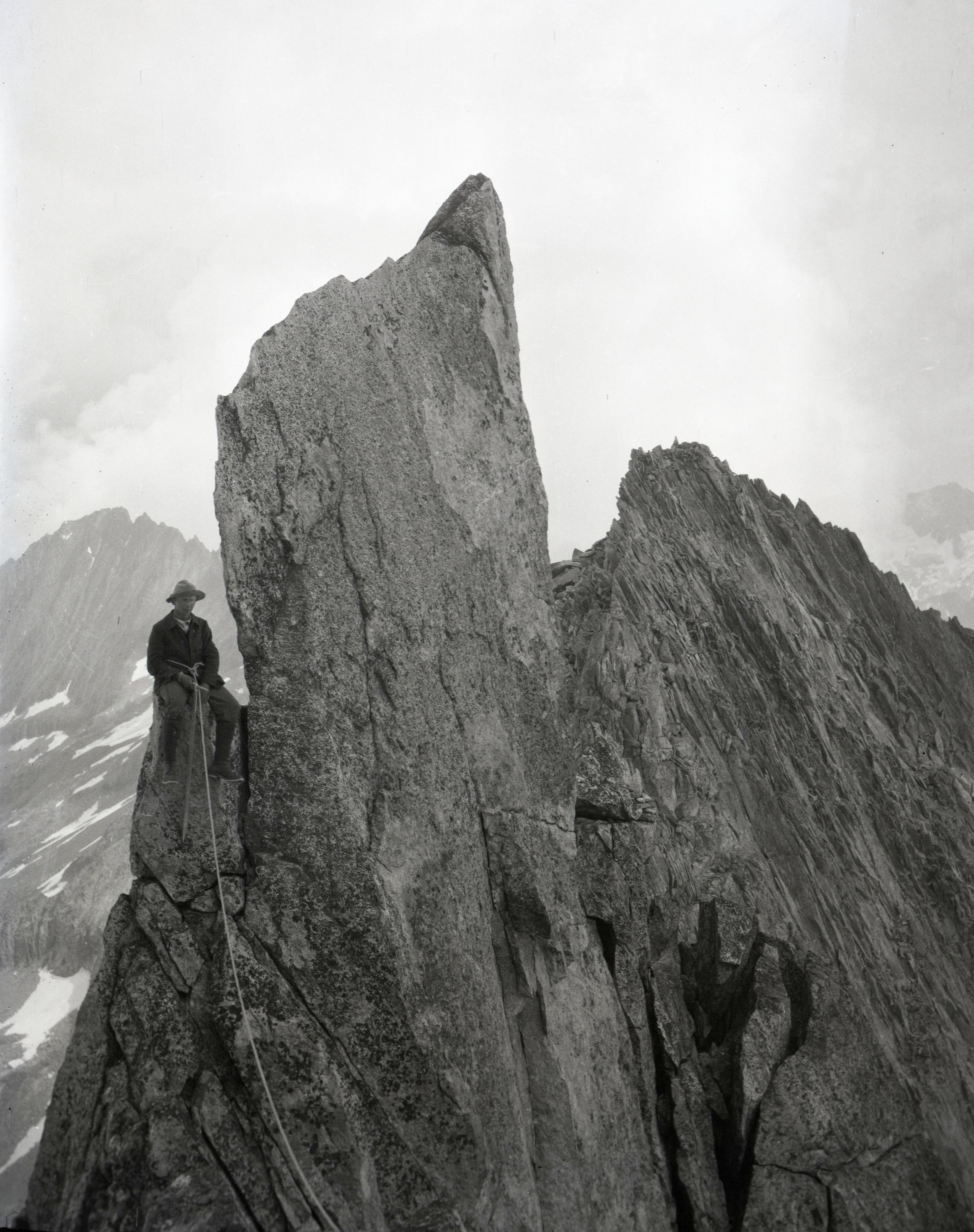

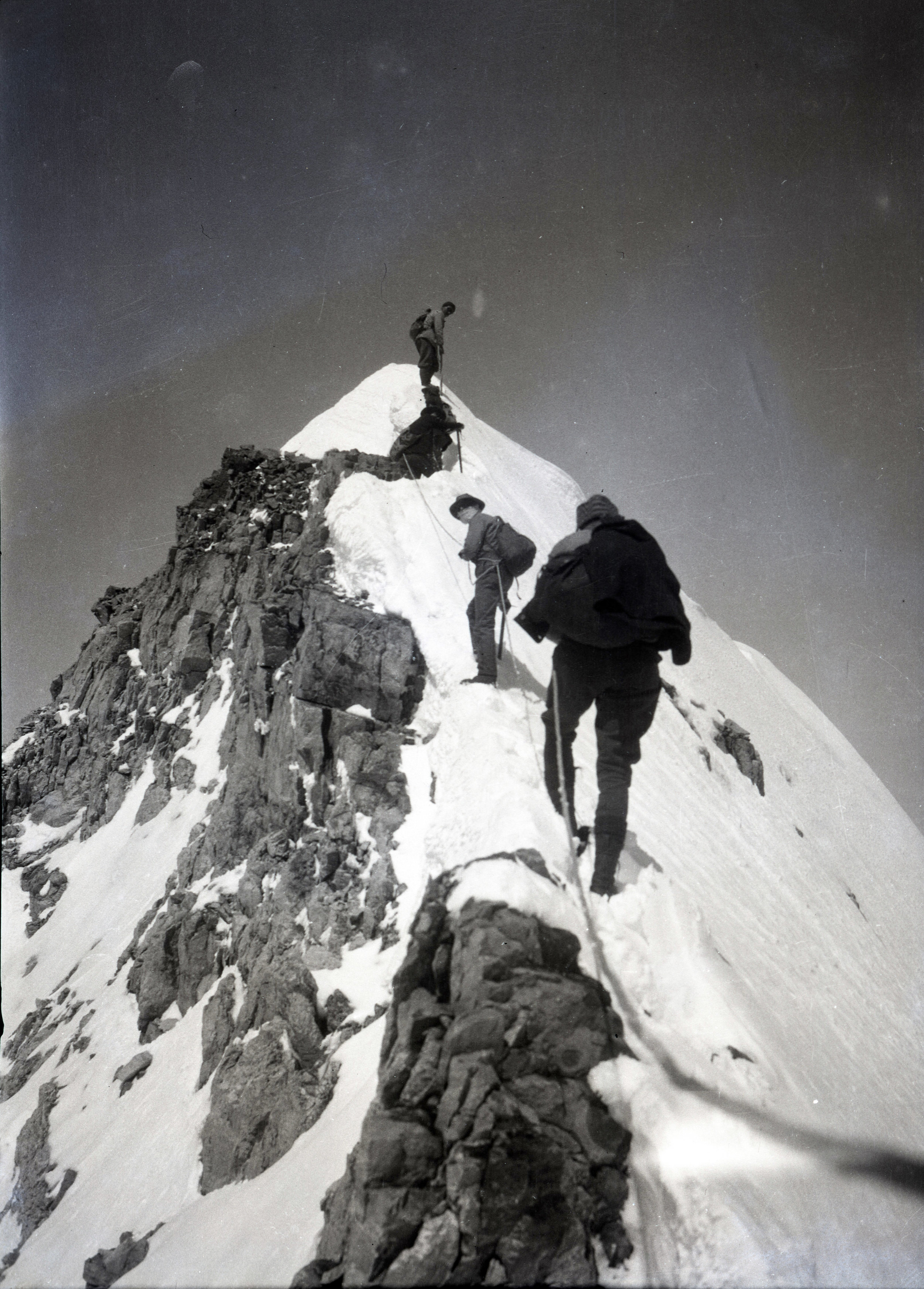

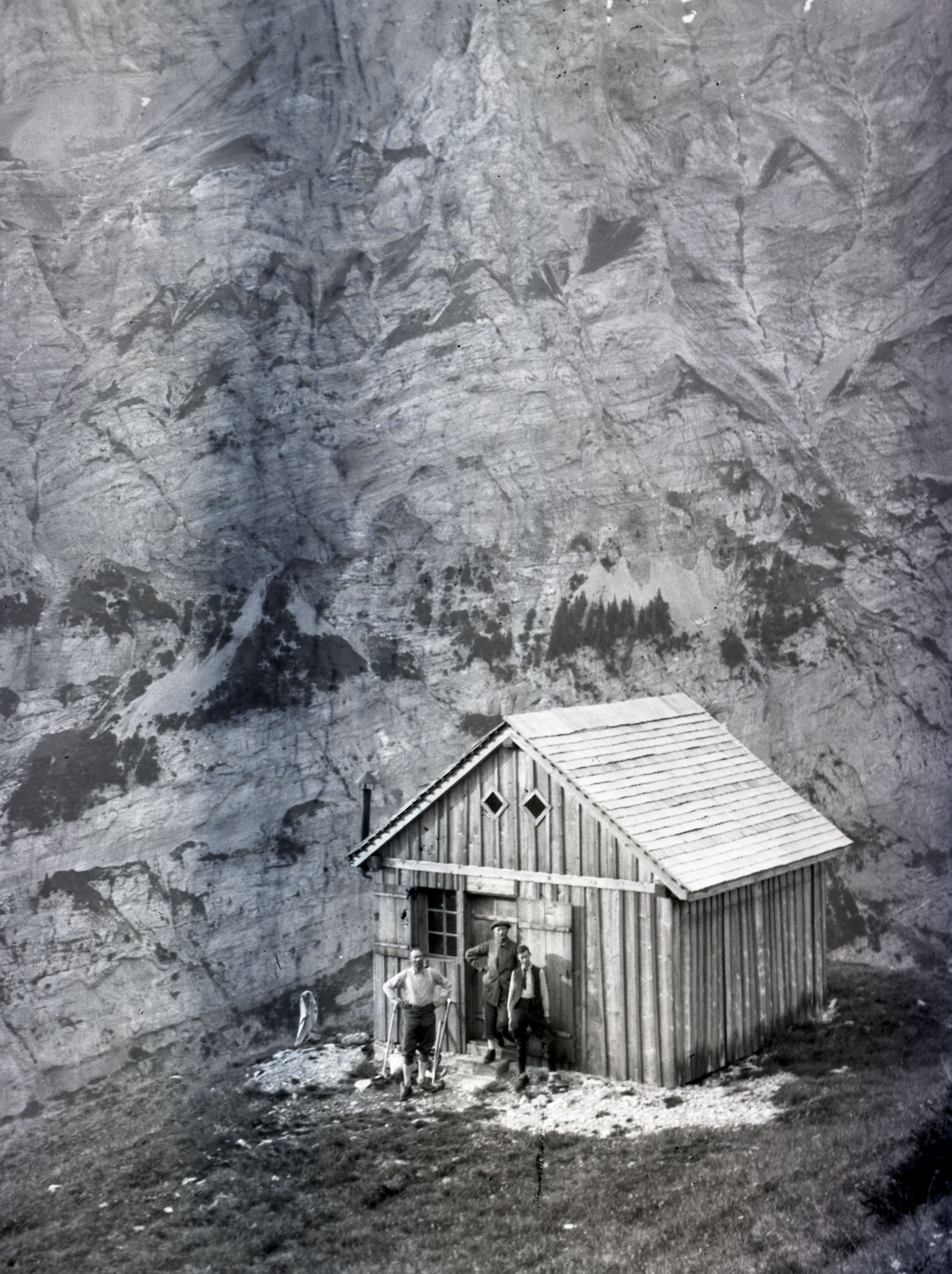

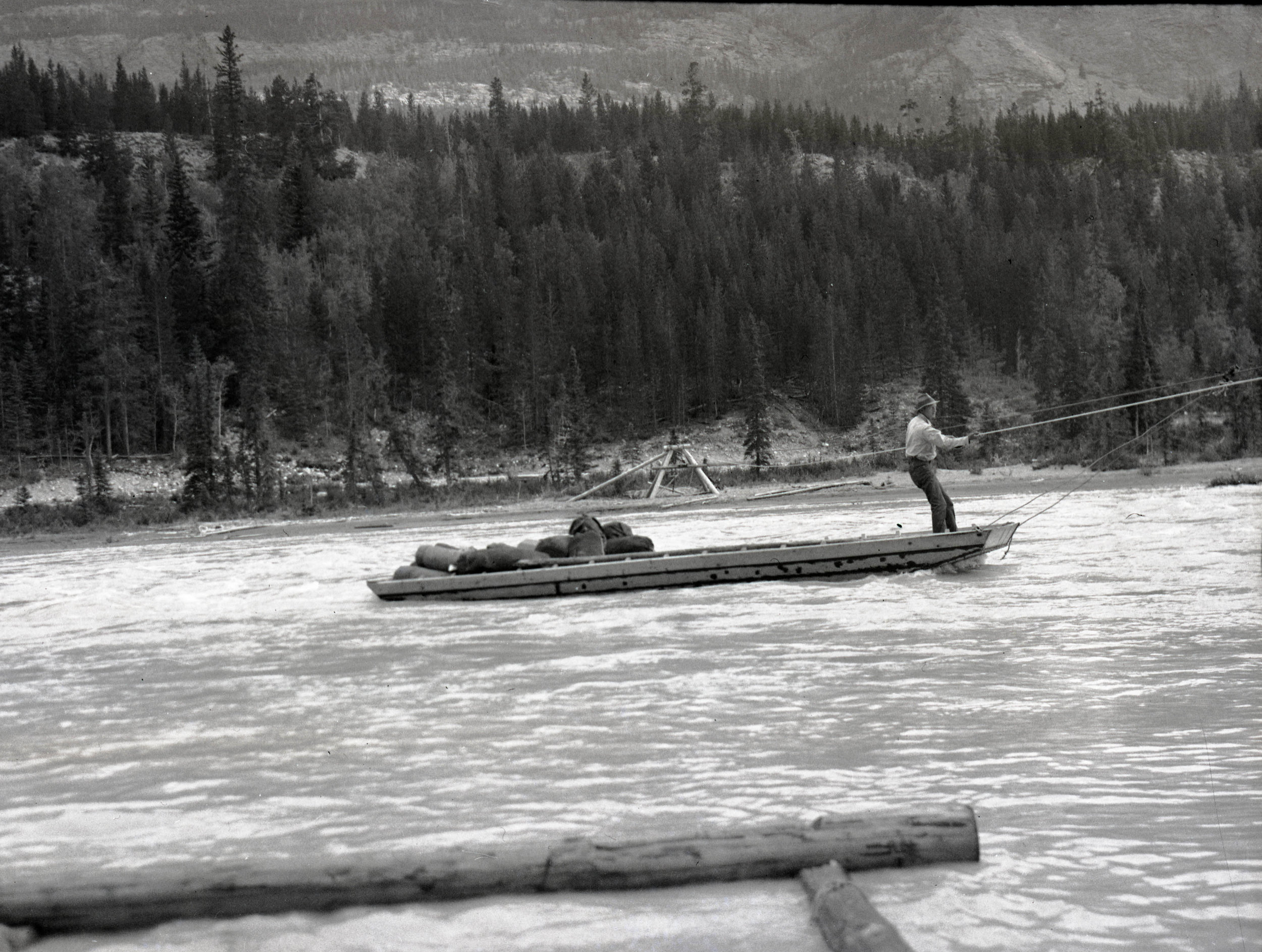

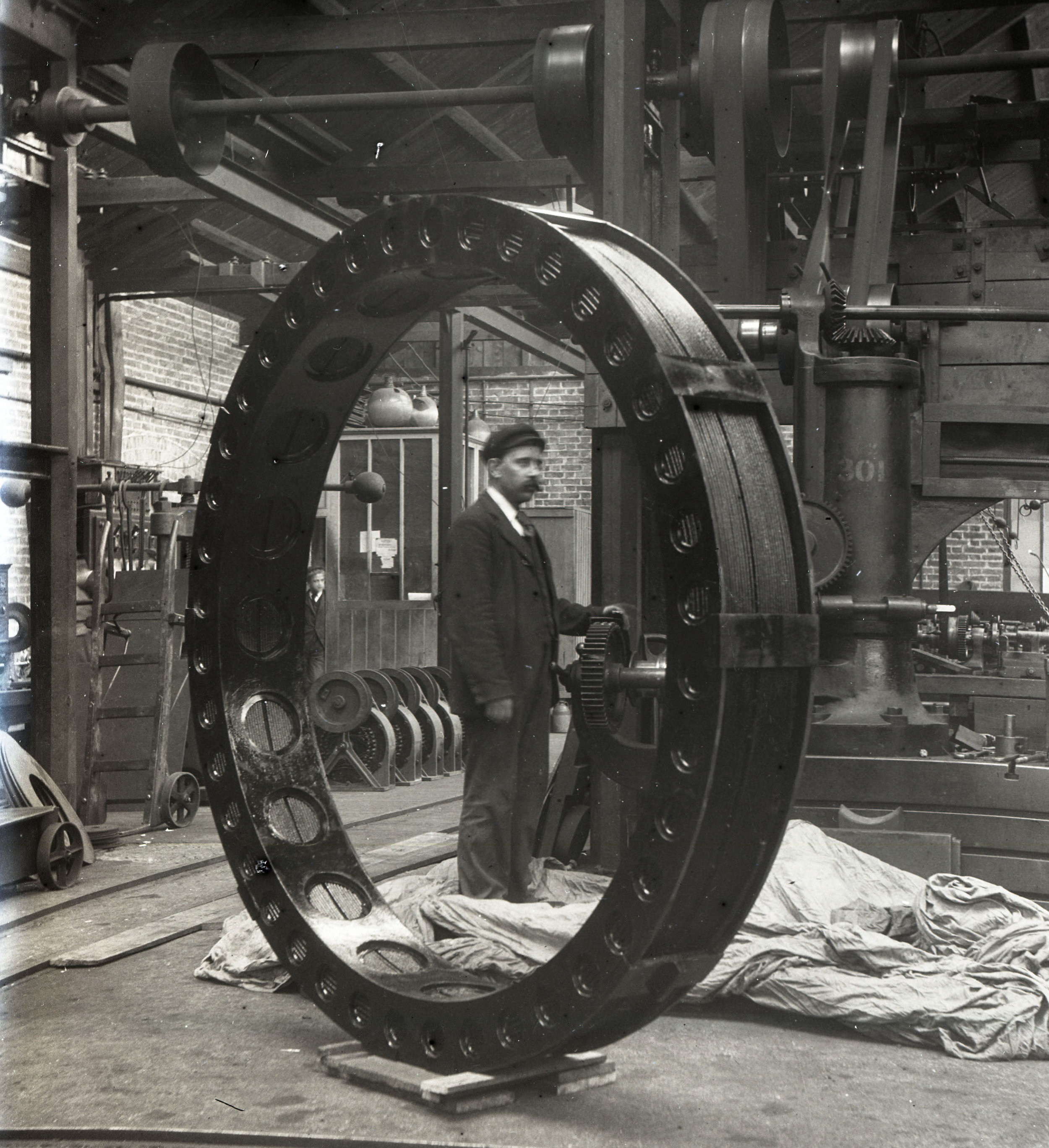

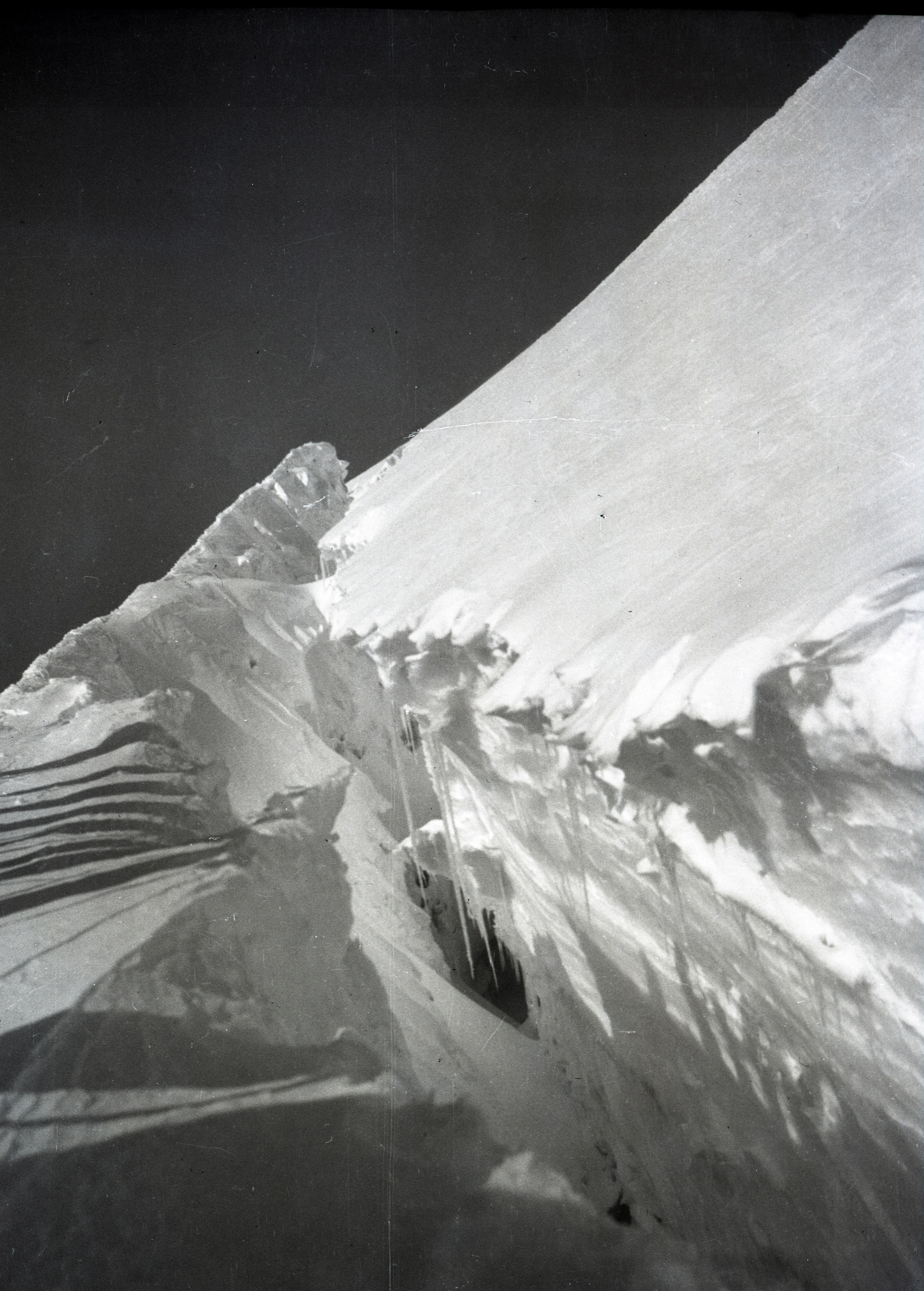

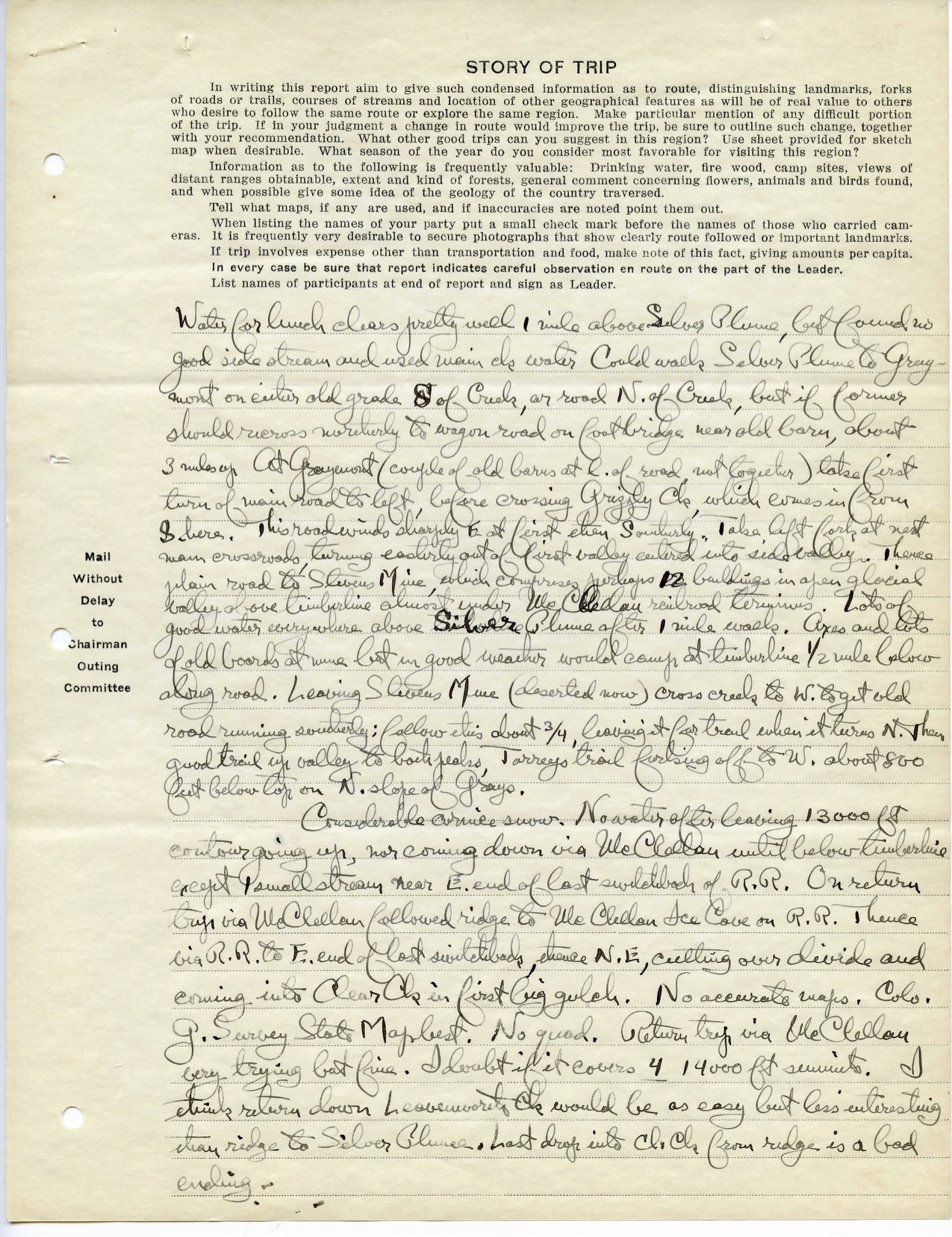

A severe storm on the first full day of summer caught two climbers high on 14,197-foot Crestone Needle in southern Colorado. After descending the Ellingwood Ledges route for about 1,000 feet, the two spent a cold night on a tiny ledge (circled). Photo: Patrick Fiore.

The Prescription - October 2020

EPIC ON ELLINGWOOD LEDGES

STRANDED | Storm, Darkness, Inexperience

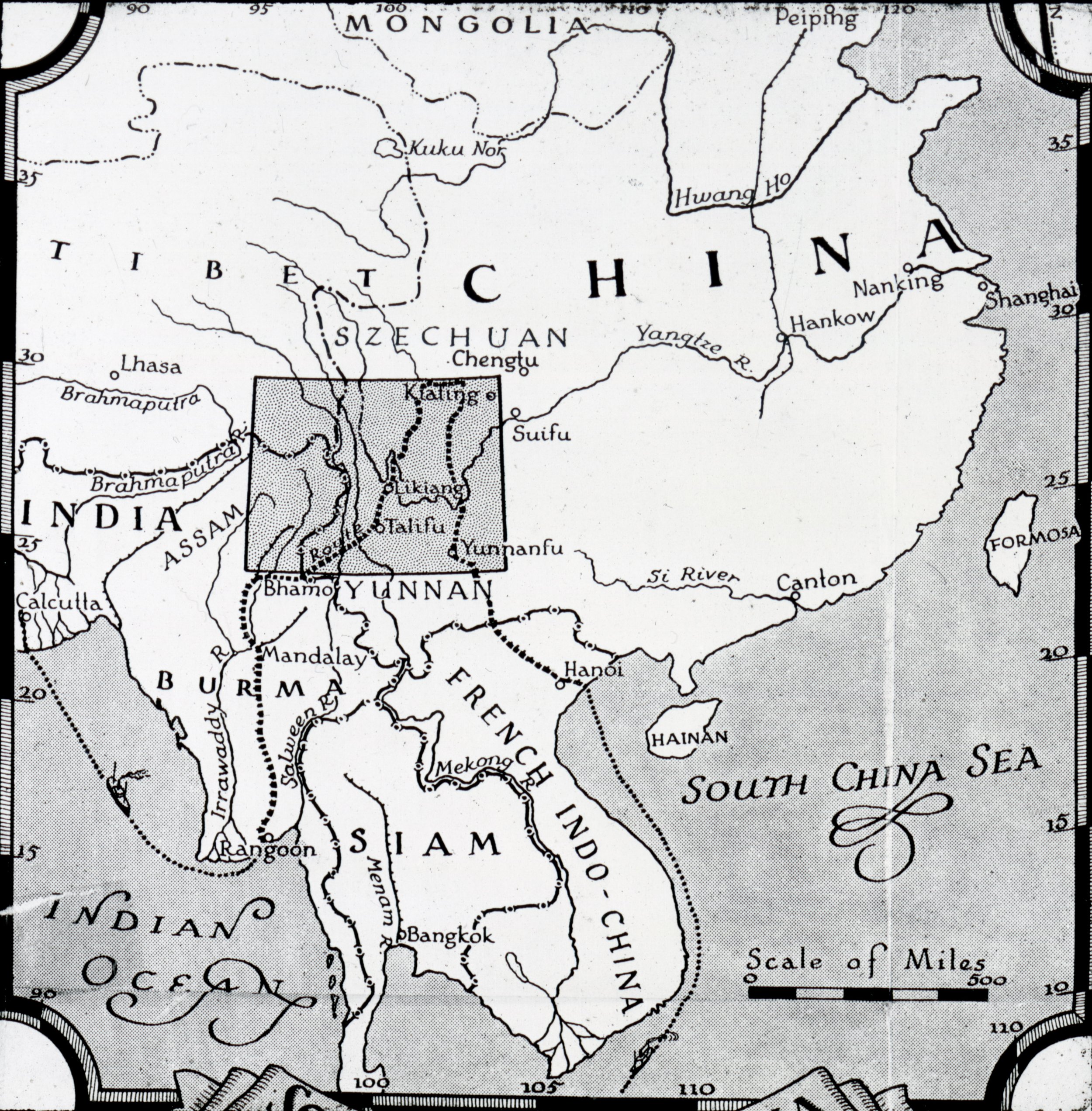

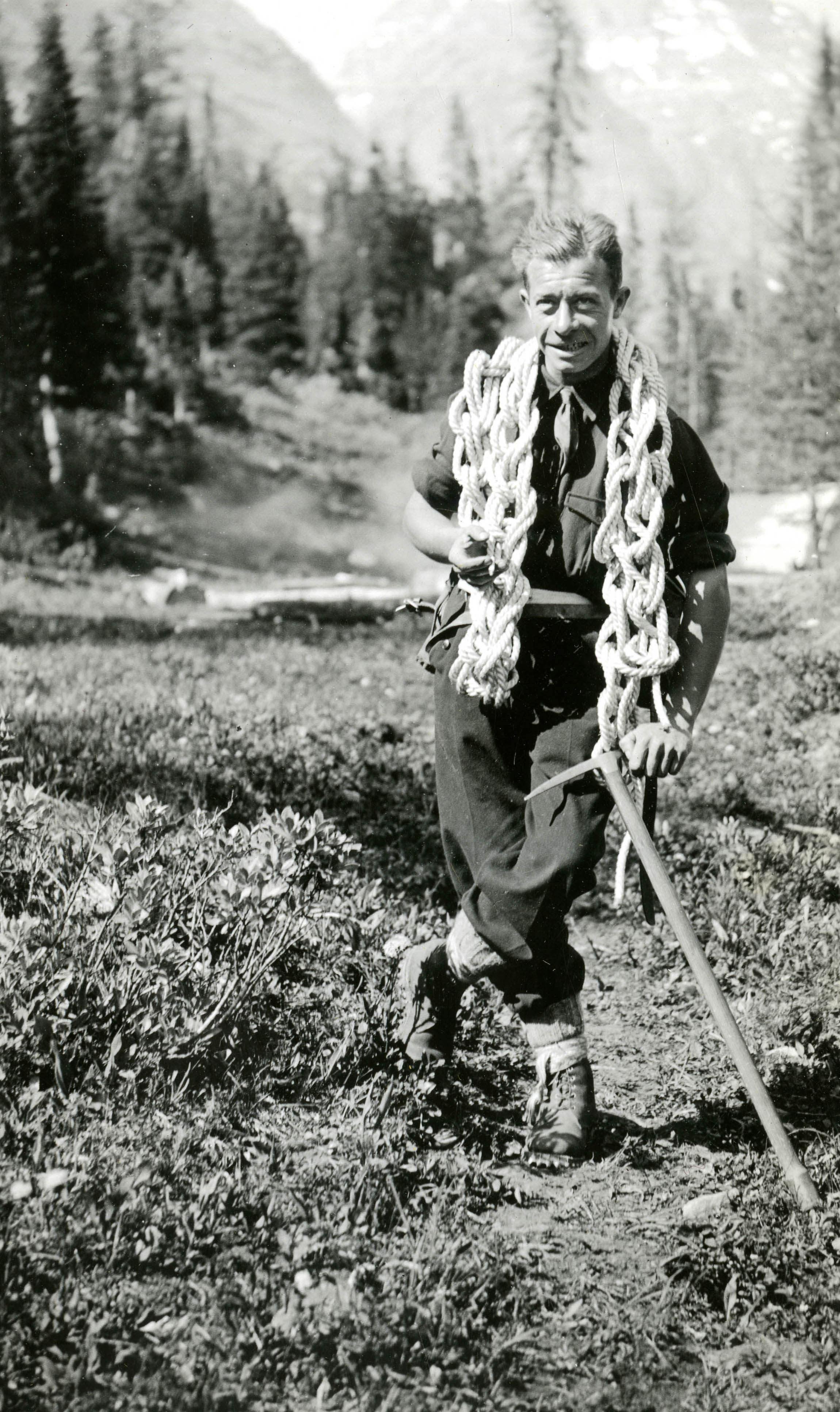

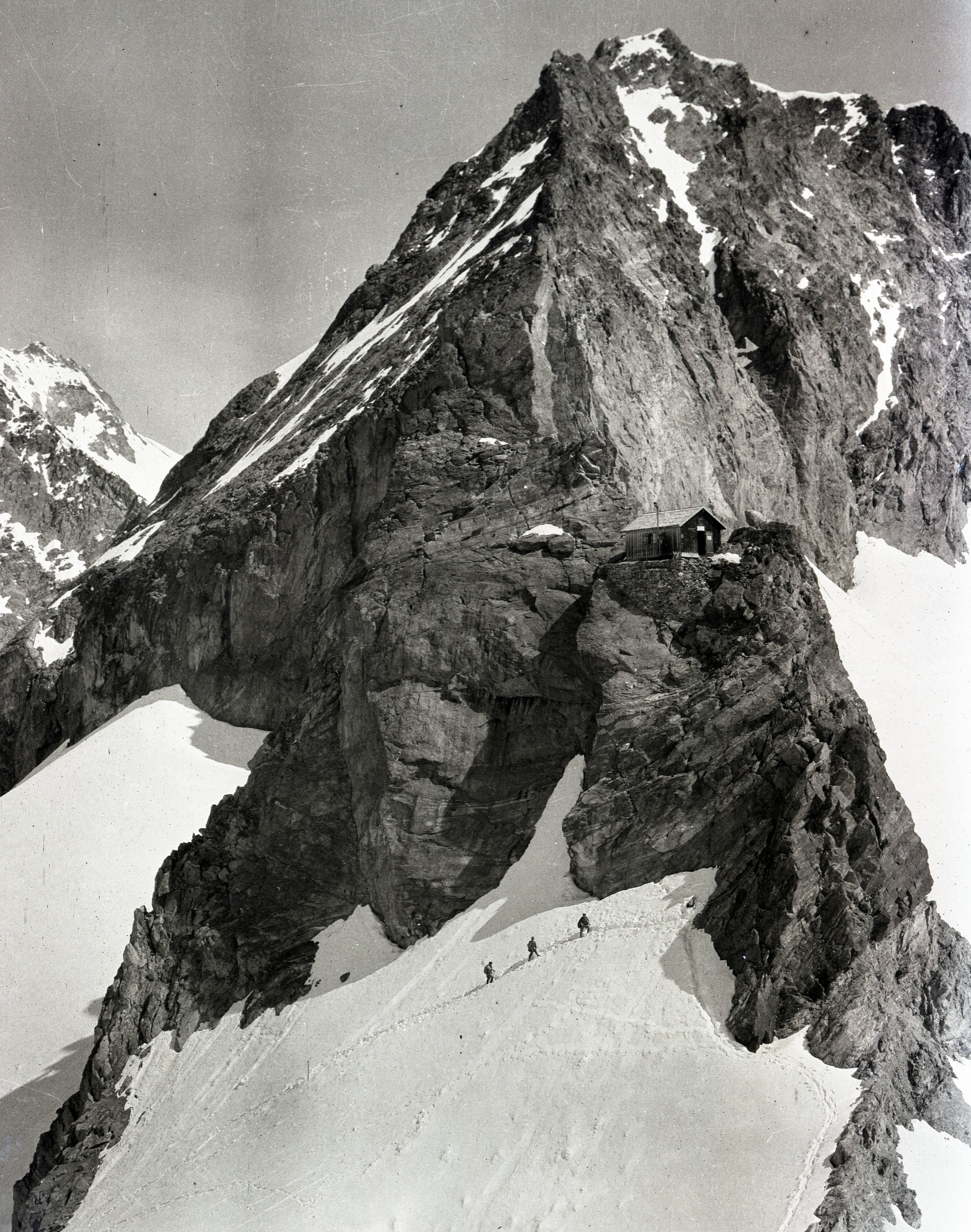

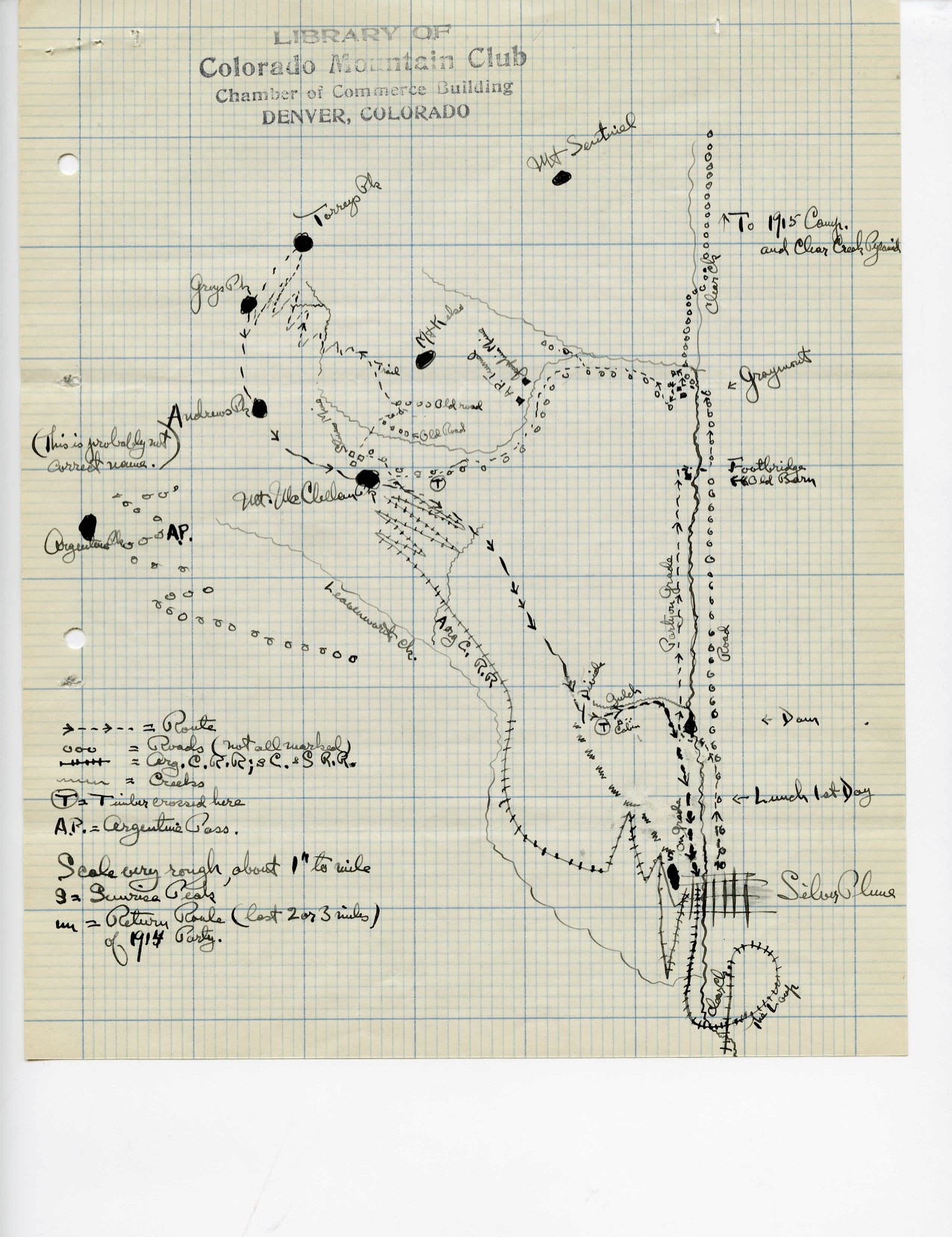

On Friday, June 21, 2019, two climbers from Kansas (ages 23 and 30) drove up to the east side of the Sangre de Cristo Range. Their goal was the Ellingwood Ledges (a.k.a. Ellingwood Arête) on the east side of Crestone Needle, one of the “Fifty Classic Climbs of North America.” The 2,000-foot route ends at the summit of the 14,197-foot peak.

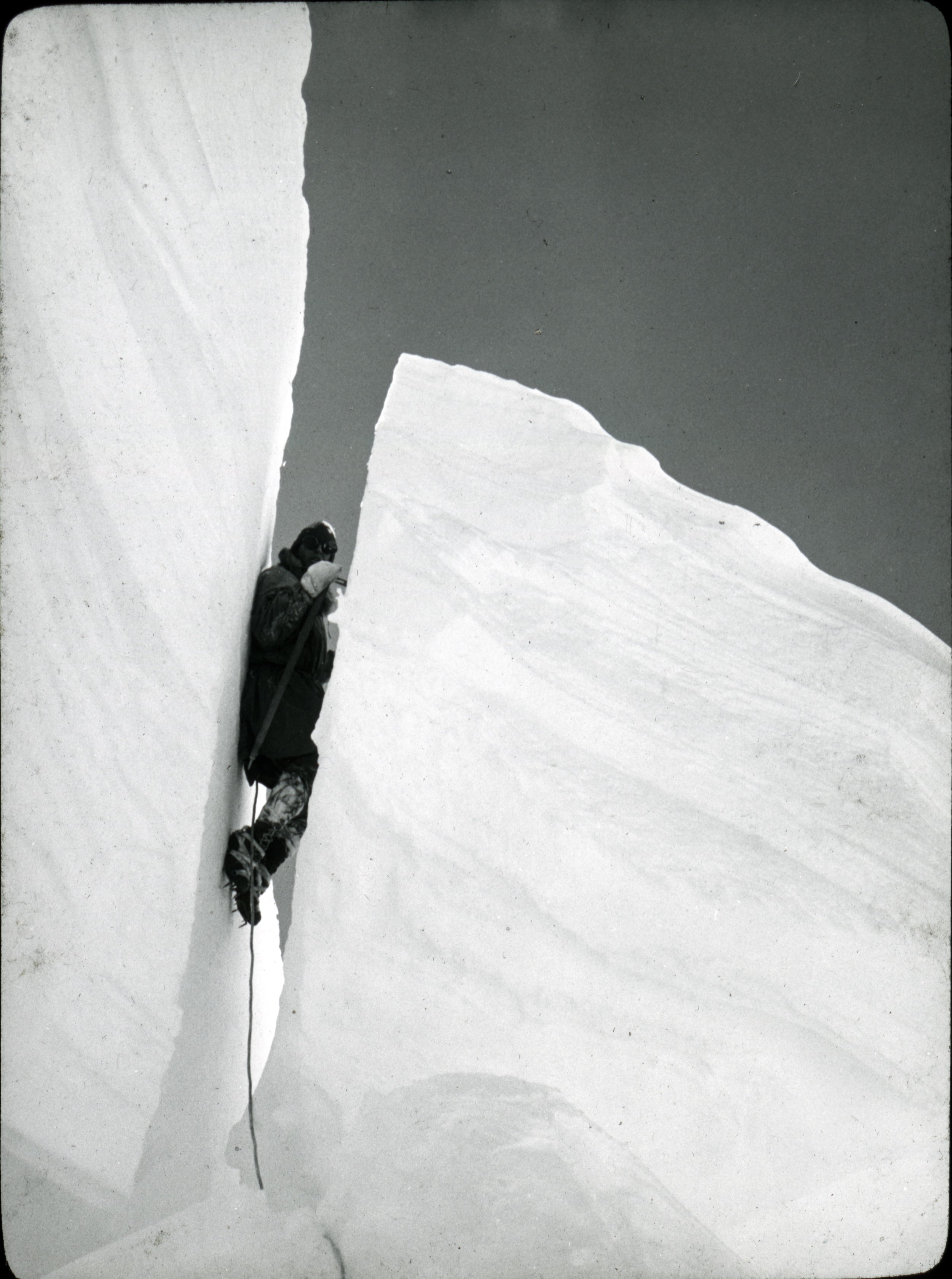

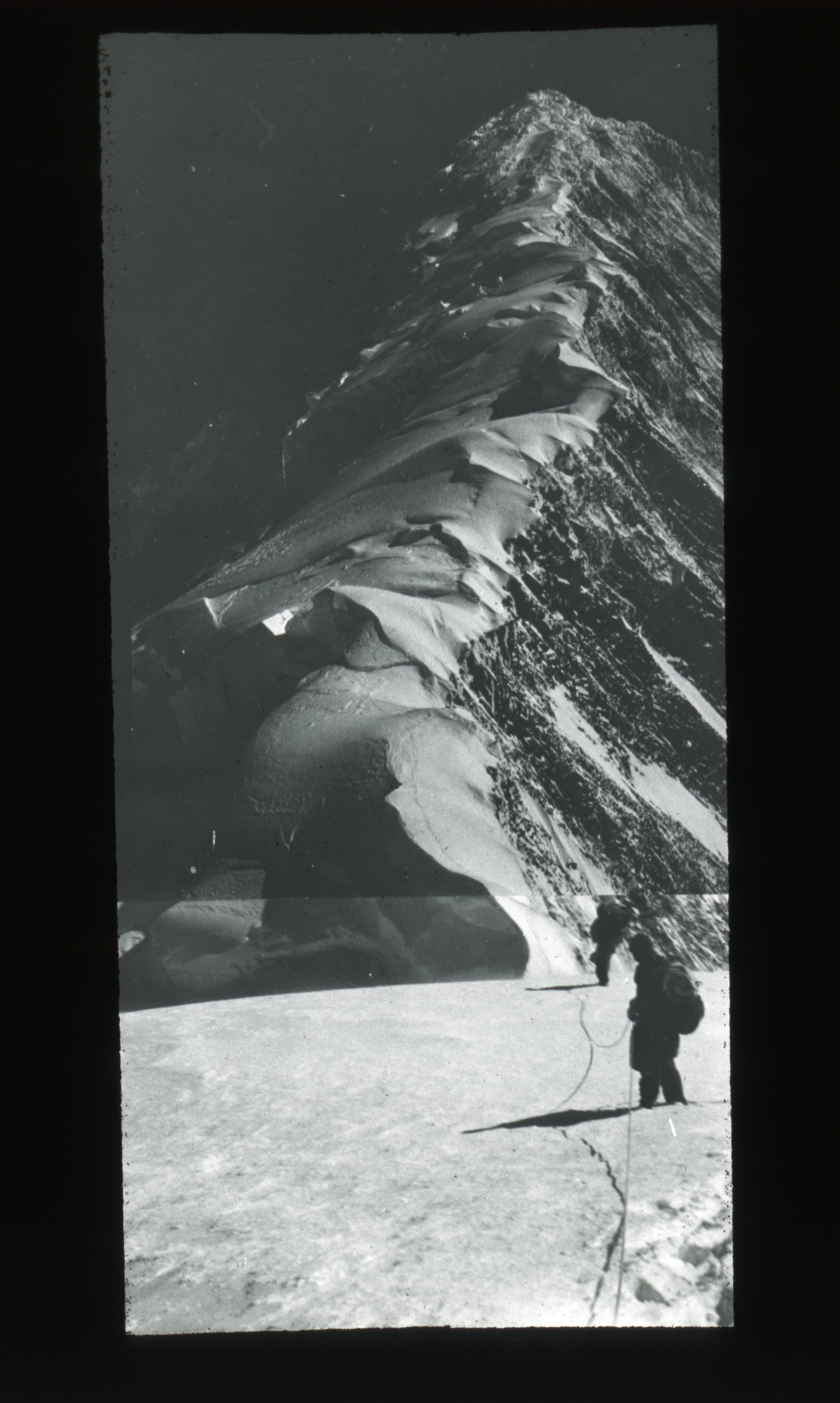

The next morning, under sunny skies, they started climbing at 9 a.m. via the route’s direct start. Their iPhone weather app showed a forecast of “partly cloudy with a 20% chance of showers.” Enjoying warm weather and dry rock, the duo made good time cruising the easy 5th-class pitches at the bottom and the 3rd- and 4th-class ledges in the middle of the route. However, at the route’s crux, just a few hundred feet below the summit, the 5.7 to 5.9 cracks (depending on exact route) were filled with ice. Clad in rock shoes and with no ice axes, they couldn’t climb past the thin ribbons of ice. Meanwhile, the sky turned gray as, unbeknownst to the pair, a strong winter-like storm was barreling in from the west.

Around 4 p.m. the storm hit, with intense snow showers along with thunder and lightning. The pair put on their light fleece jackets and waterproof jackets. With visibility dropping to 30 feet, they kept trying to climb, thinking safety would be gained by going over the top and descending the standard route. (In fact, the 3rd-class normal route up and down Crestone Needle is exposed and tricky to follow, and has stranded climbers even in the best weather.) Eventually, realizing they could not go up, the pair called the Custer County Sheriff’s Office to request assistance. It was about 5:30 p.m.

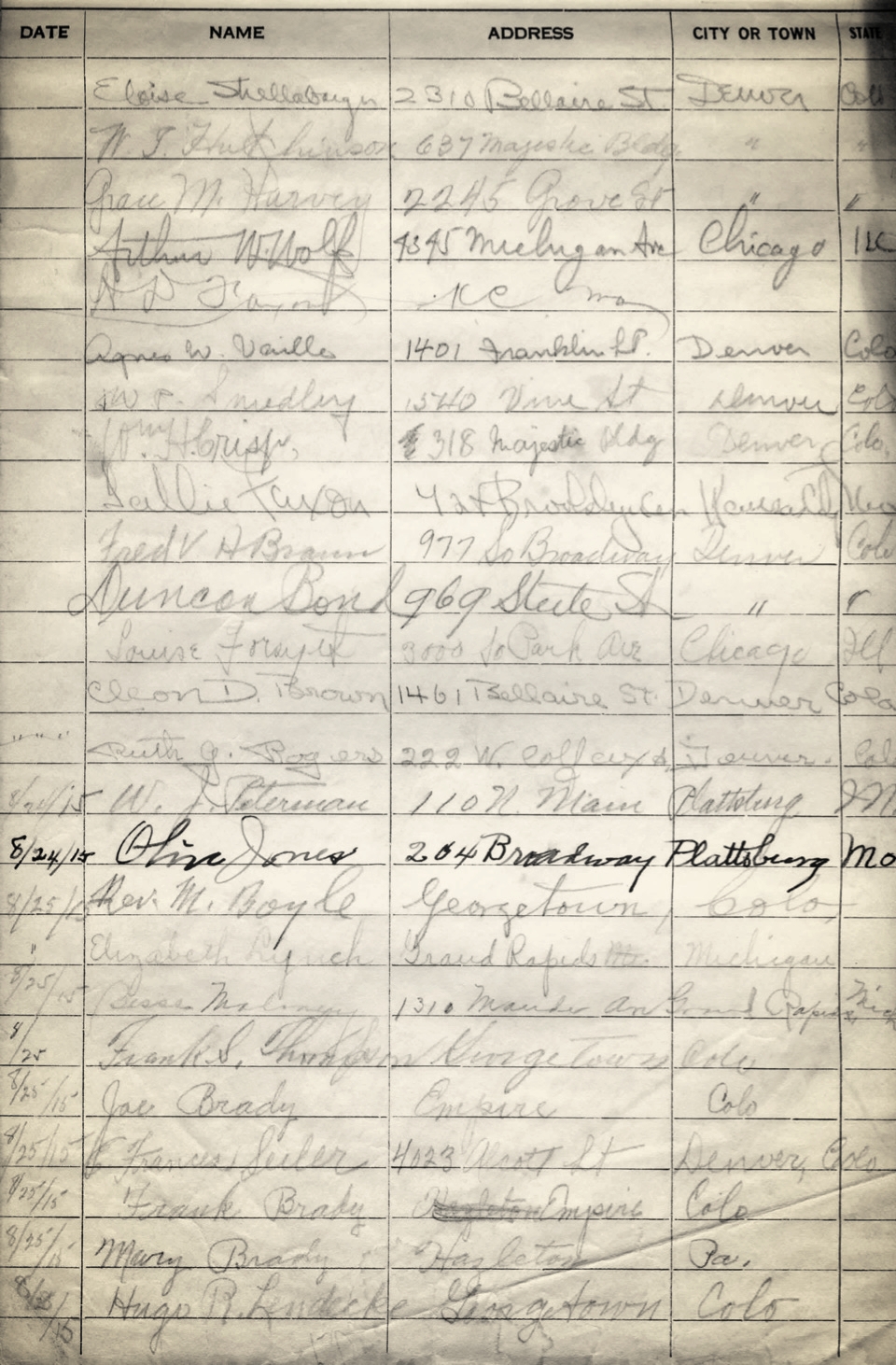

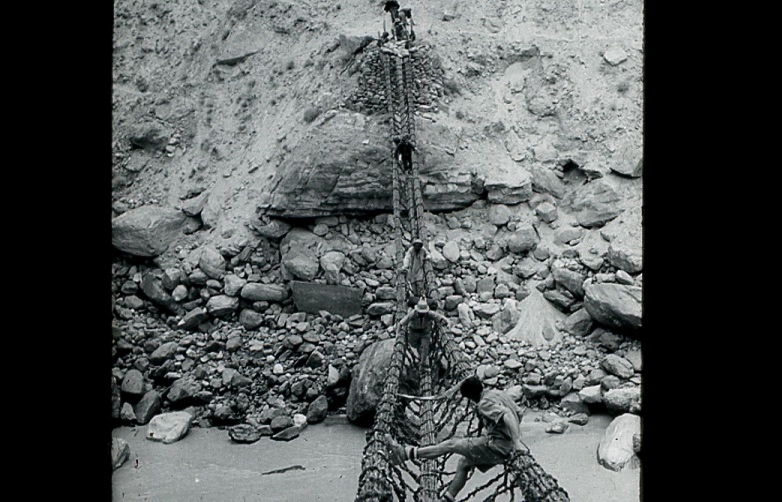

Custer County Search and Rescue (CCSAR) began planning for a technical rescue. The climbers started down, building rappel anchors and occasionally downclimbing, a descent they described as “terrifying.” They made steady progress and continued to give updates to CCSAR. (Cell service is very good high on the Crestones.) At approximately 9:30 p.m. and at 13,030 feet, soaked and shivering hard, and nearly out of gear to build anchors, the pair grew concerned their fatigue could affect their safety if they continued. In a call with CCSAR, a senior member told them not to continue down if they were not completely confident in their anchors. They decided to stop and wait for morning on a snow-covered ledge about as wide as a lawn chair.

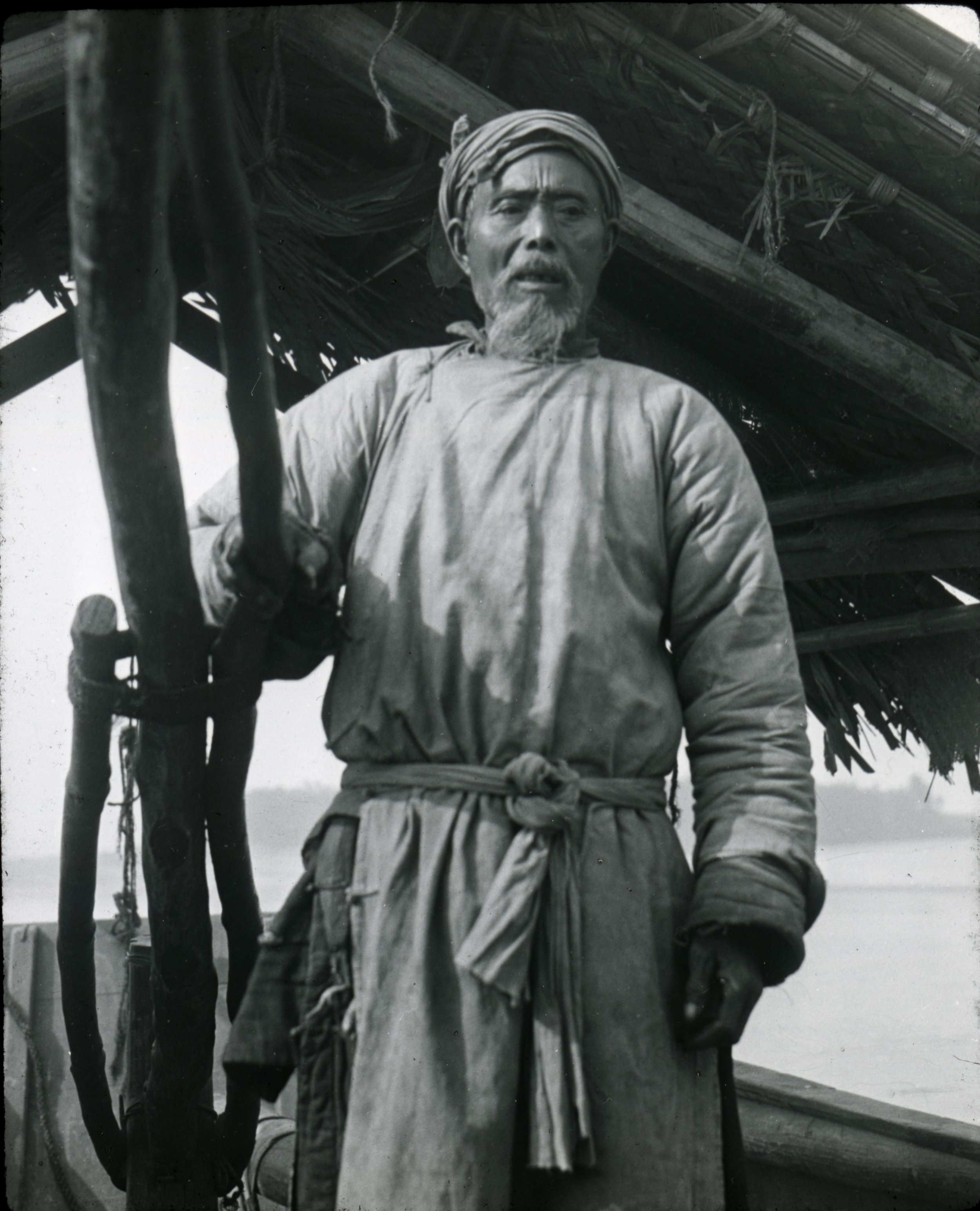

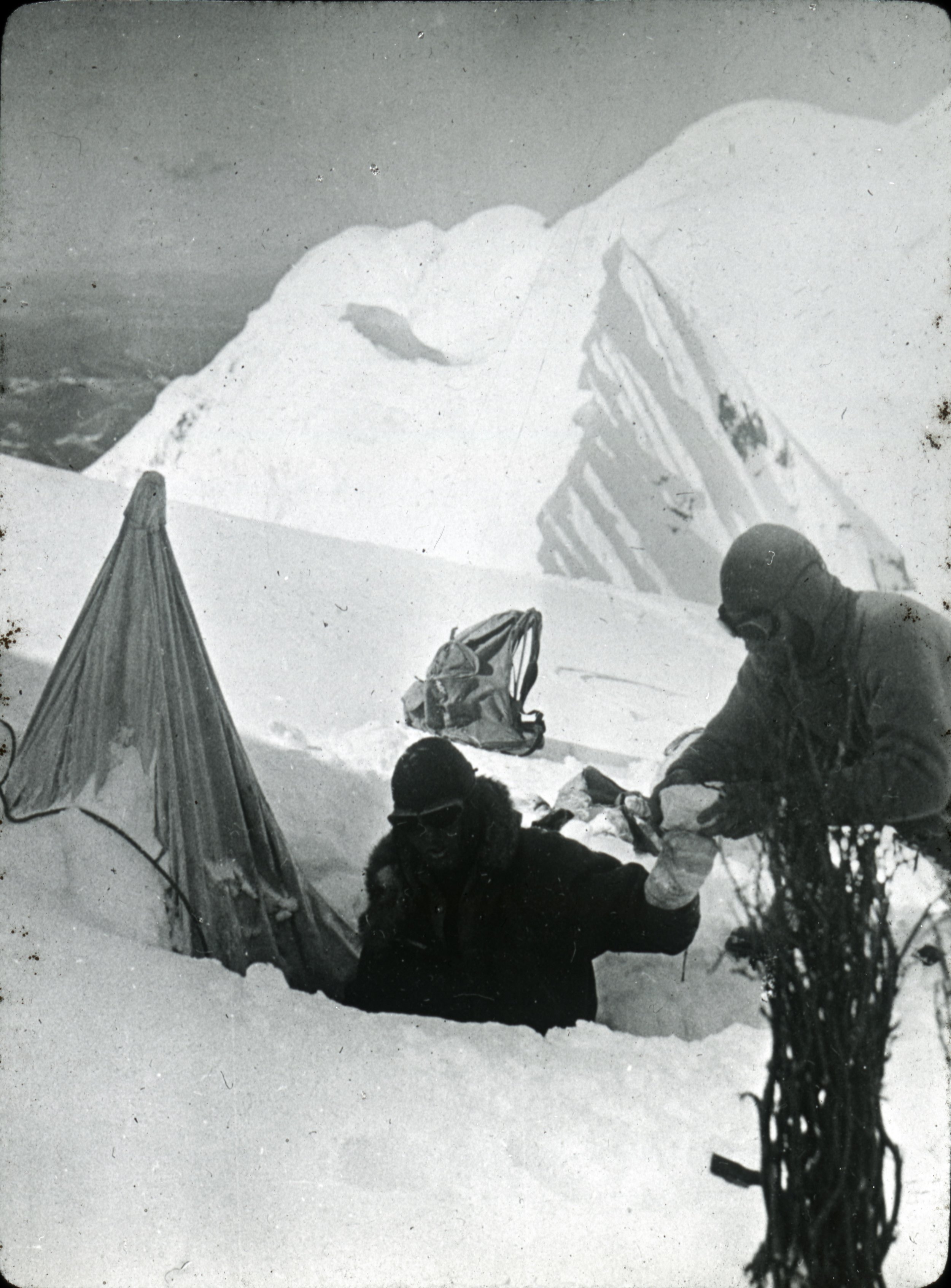

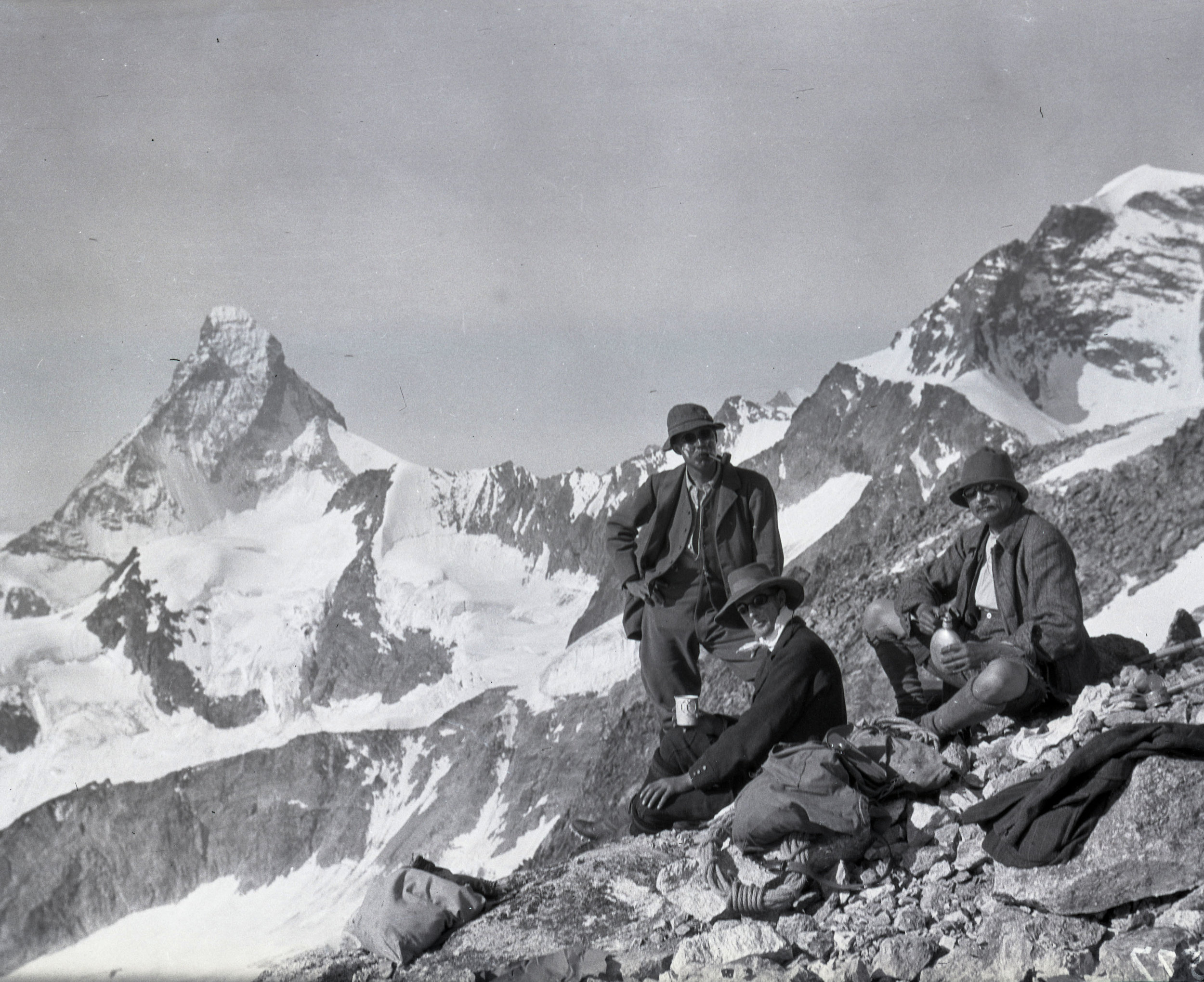

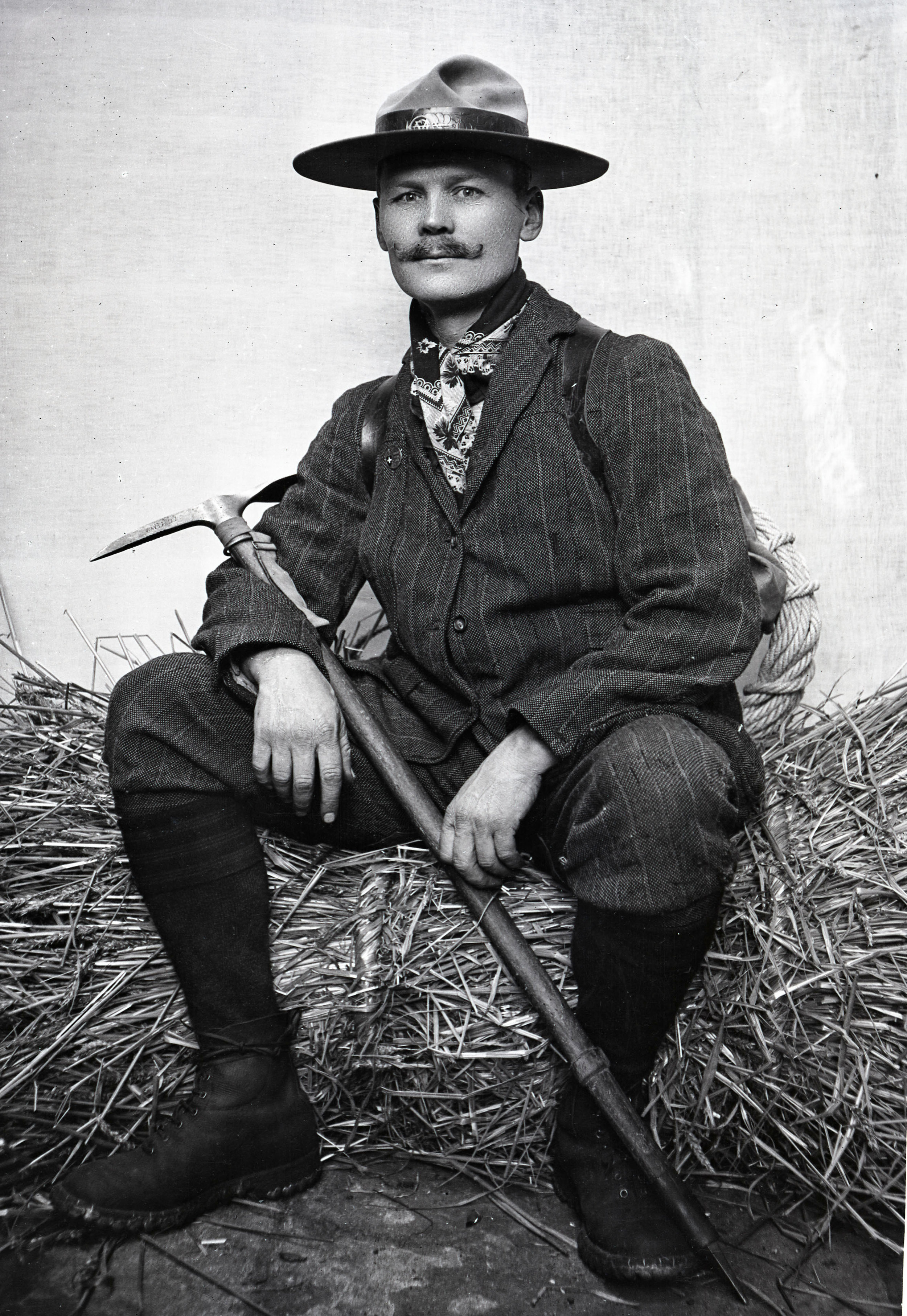

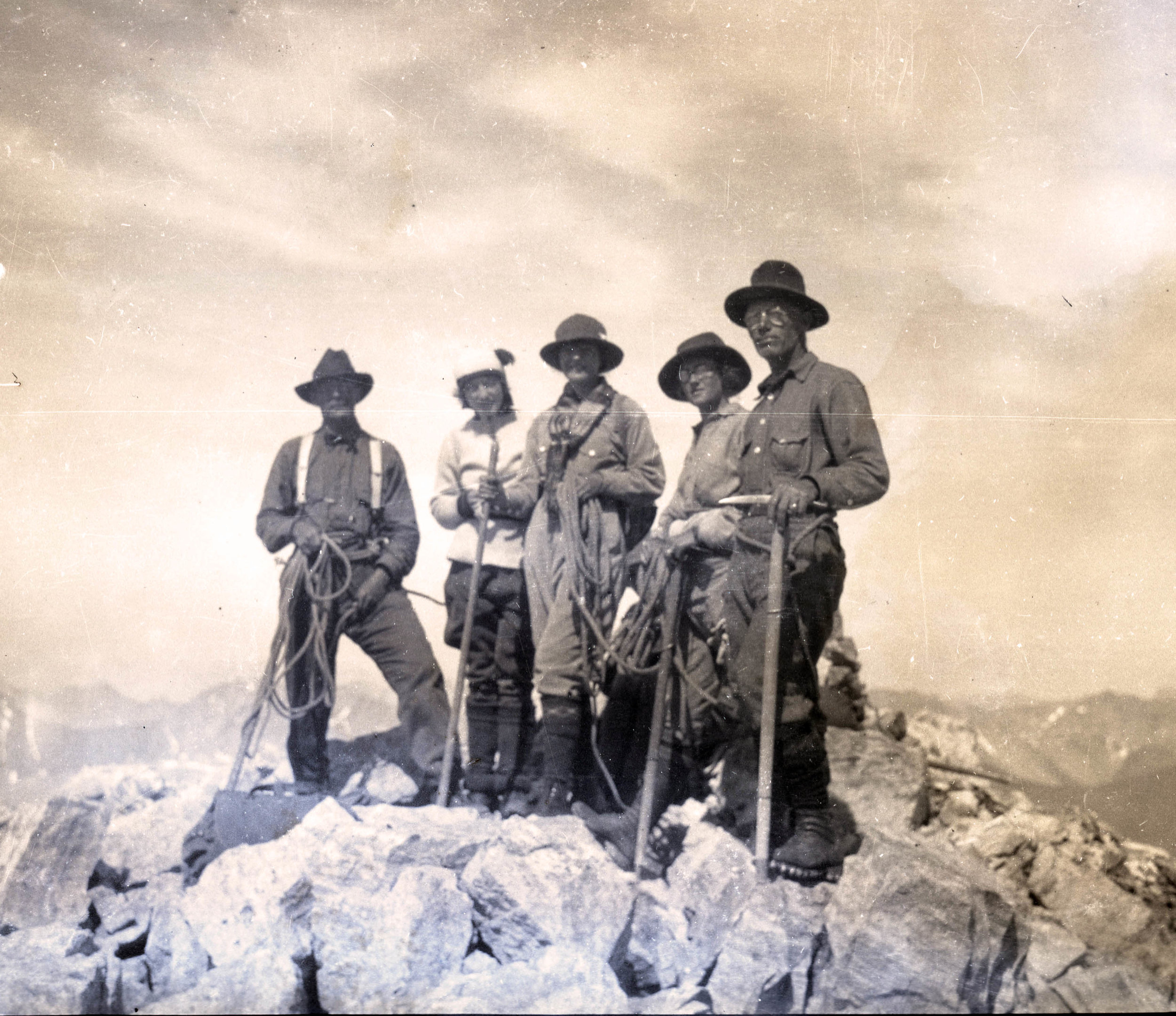

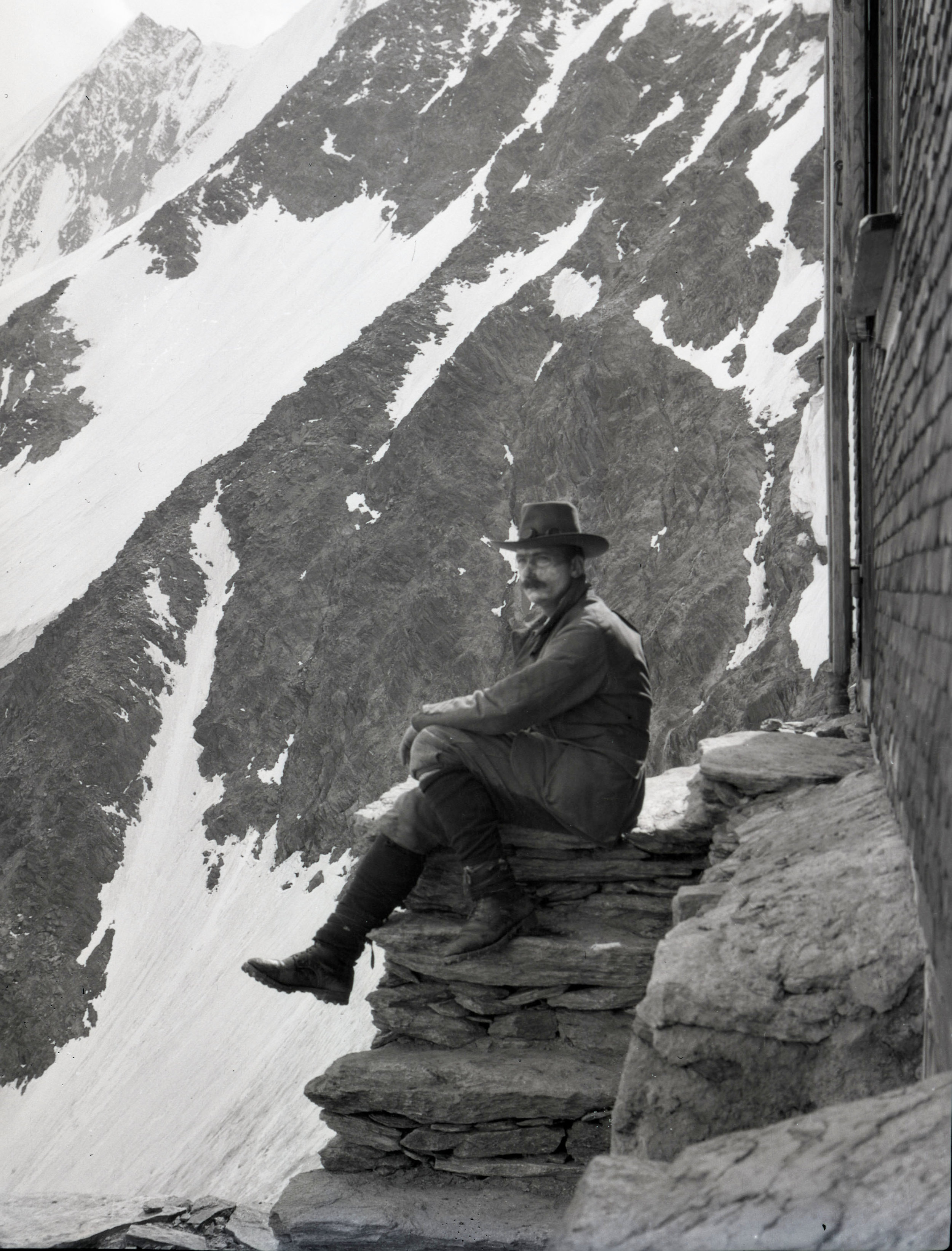

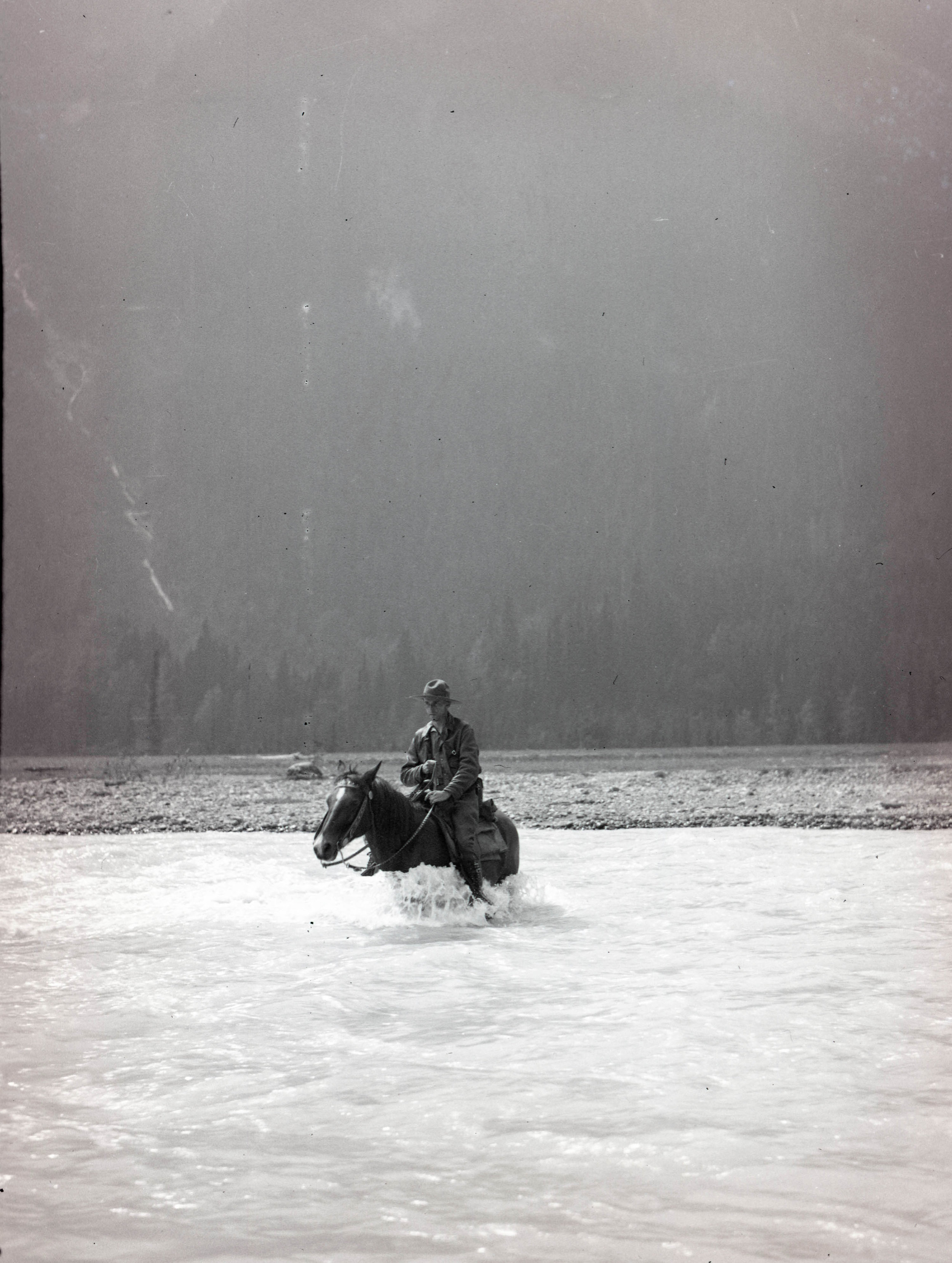

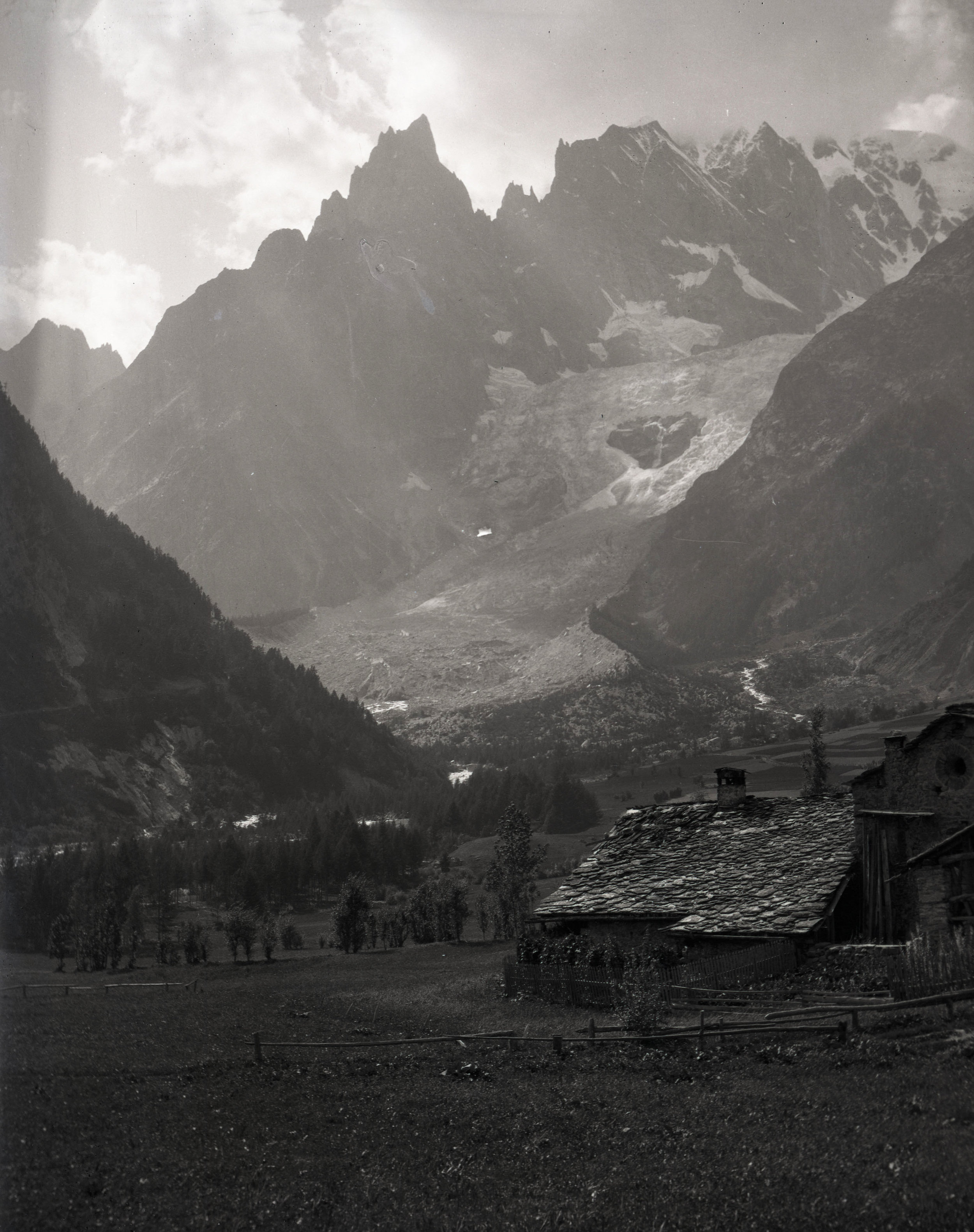

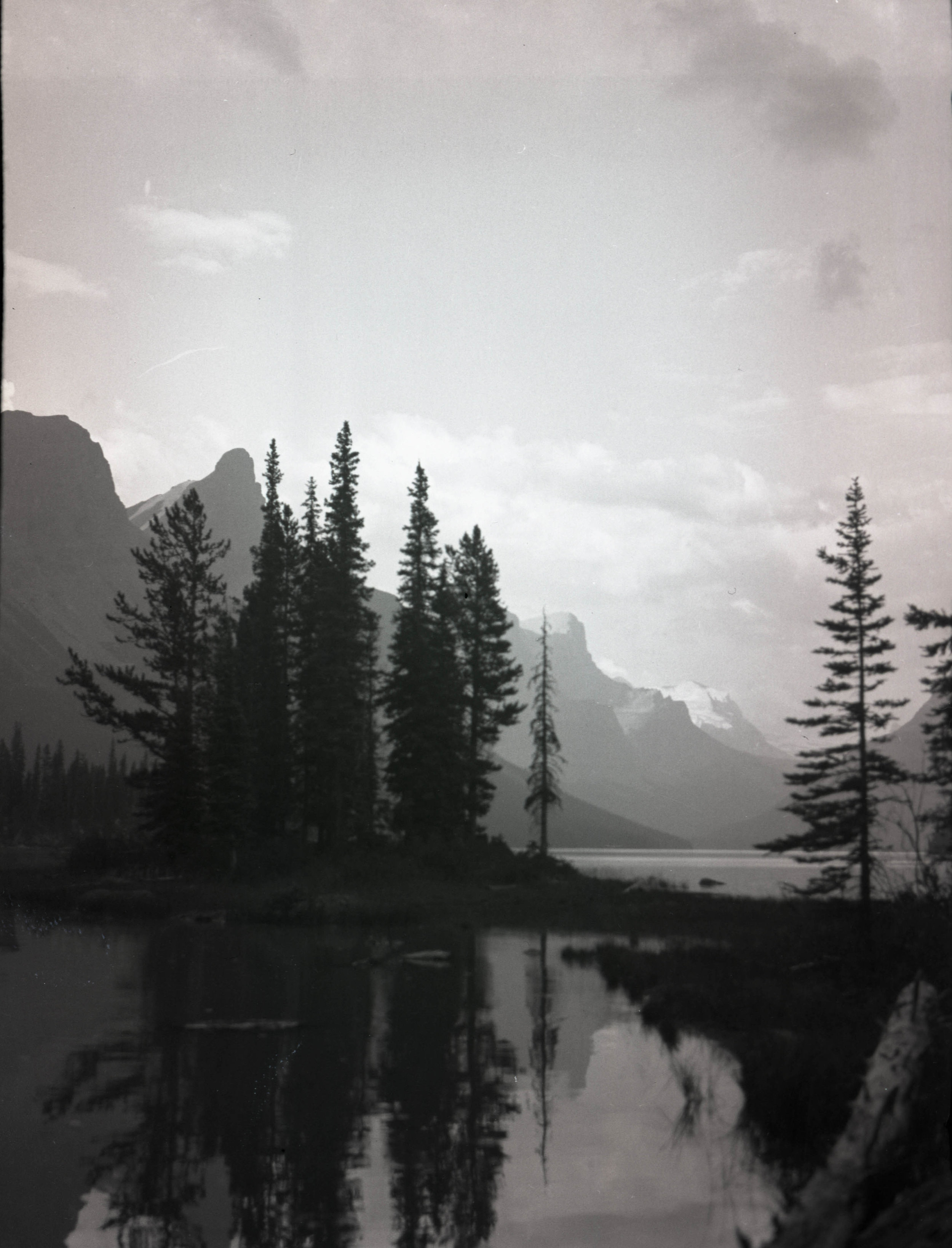

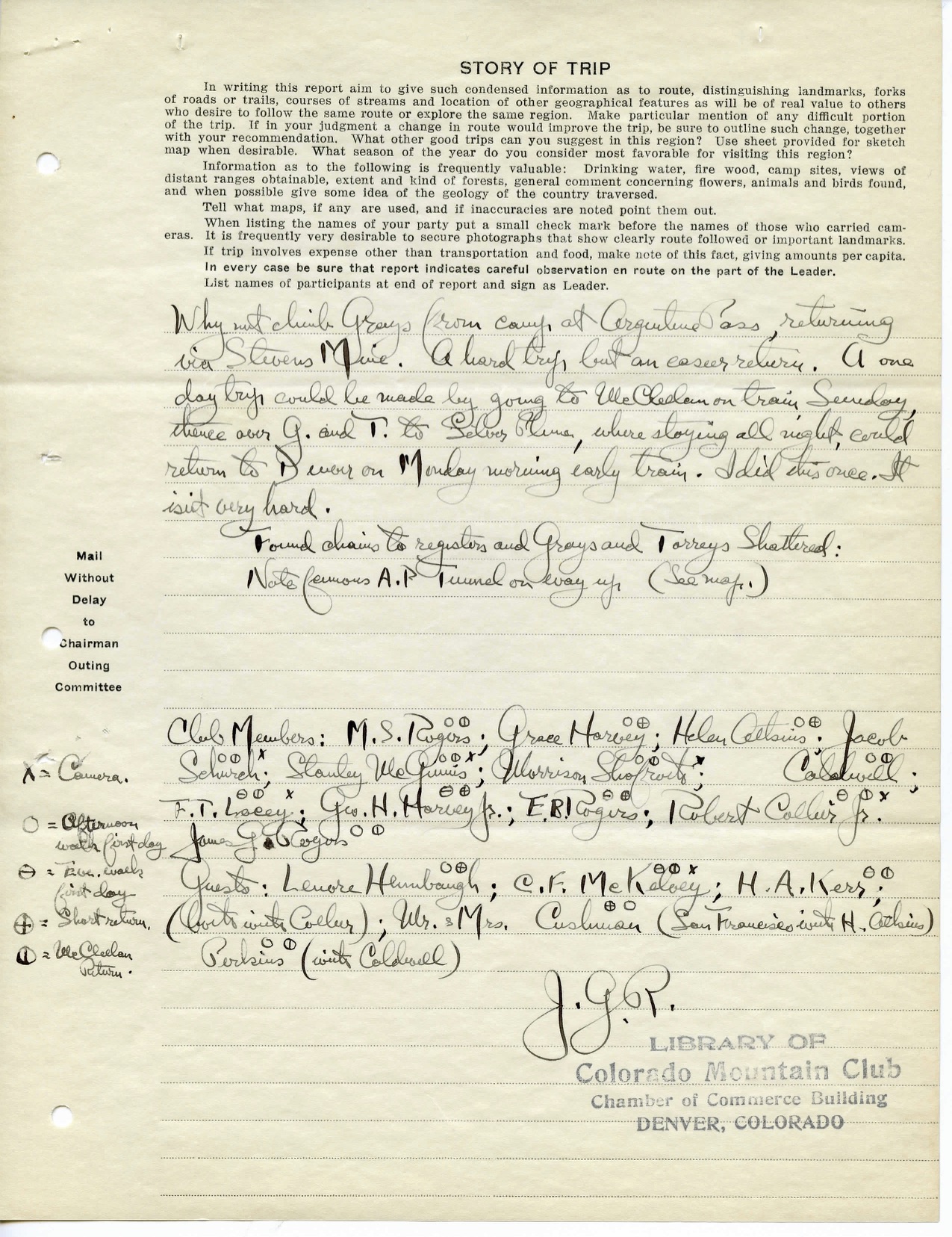

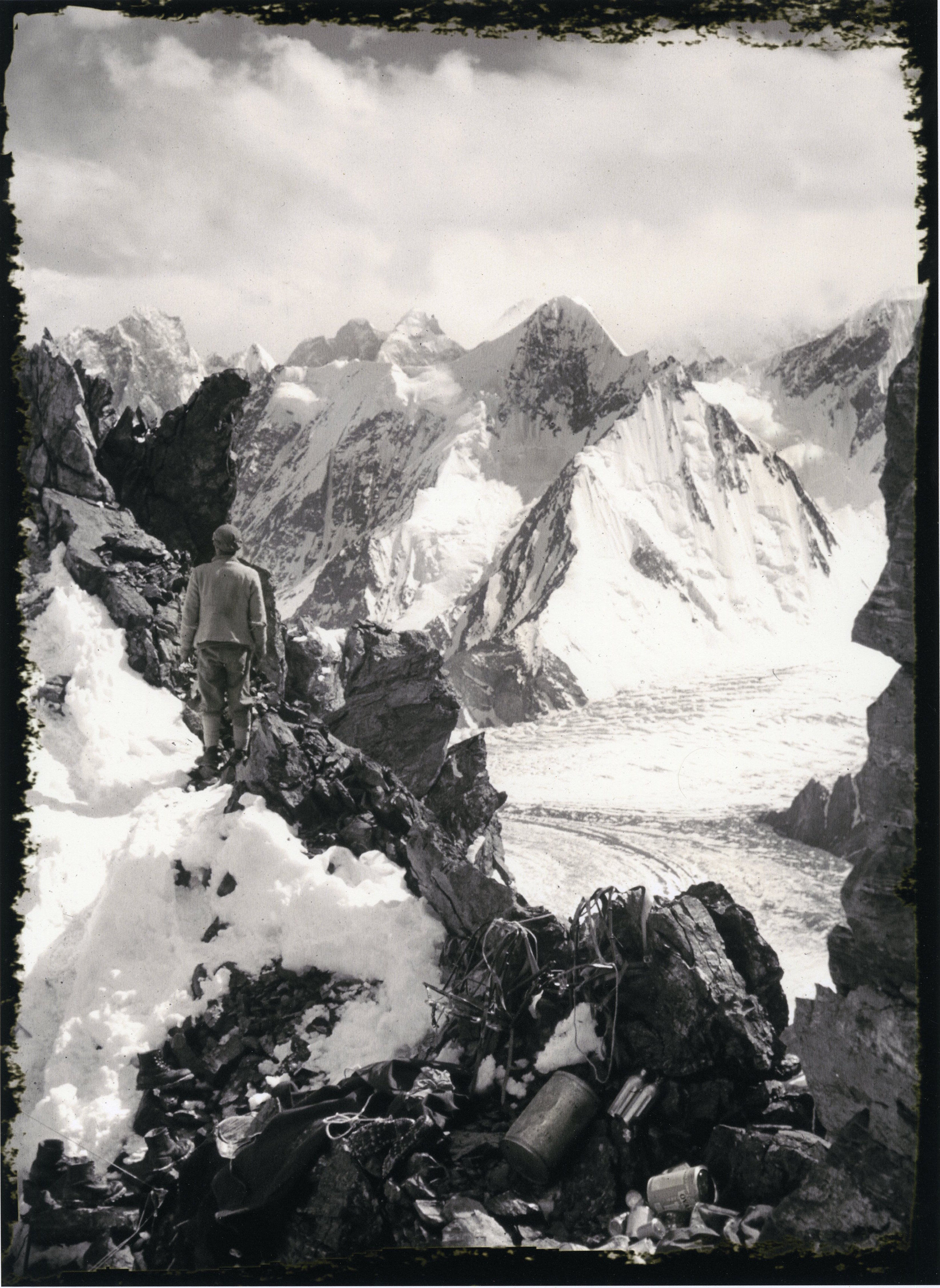

Rescuers staging below Crestone Needle in the Sangre de Cristo Range in southern Colorado. Photo courtesy of Dale Atkins.

Given the complexity of the situation, CCSAR began planning a parallel rescue effort: one ground-based and another by helicopter hoist. Members of various other rescue teams started toward the area to help, and a line of communication was opened with the Colorado Army National Guard (COANG).

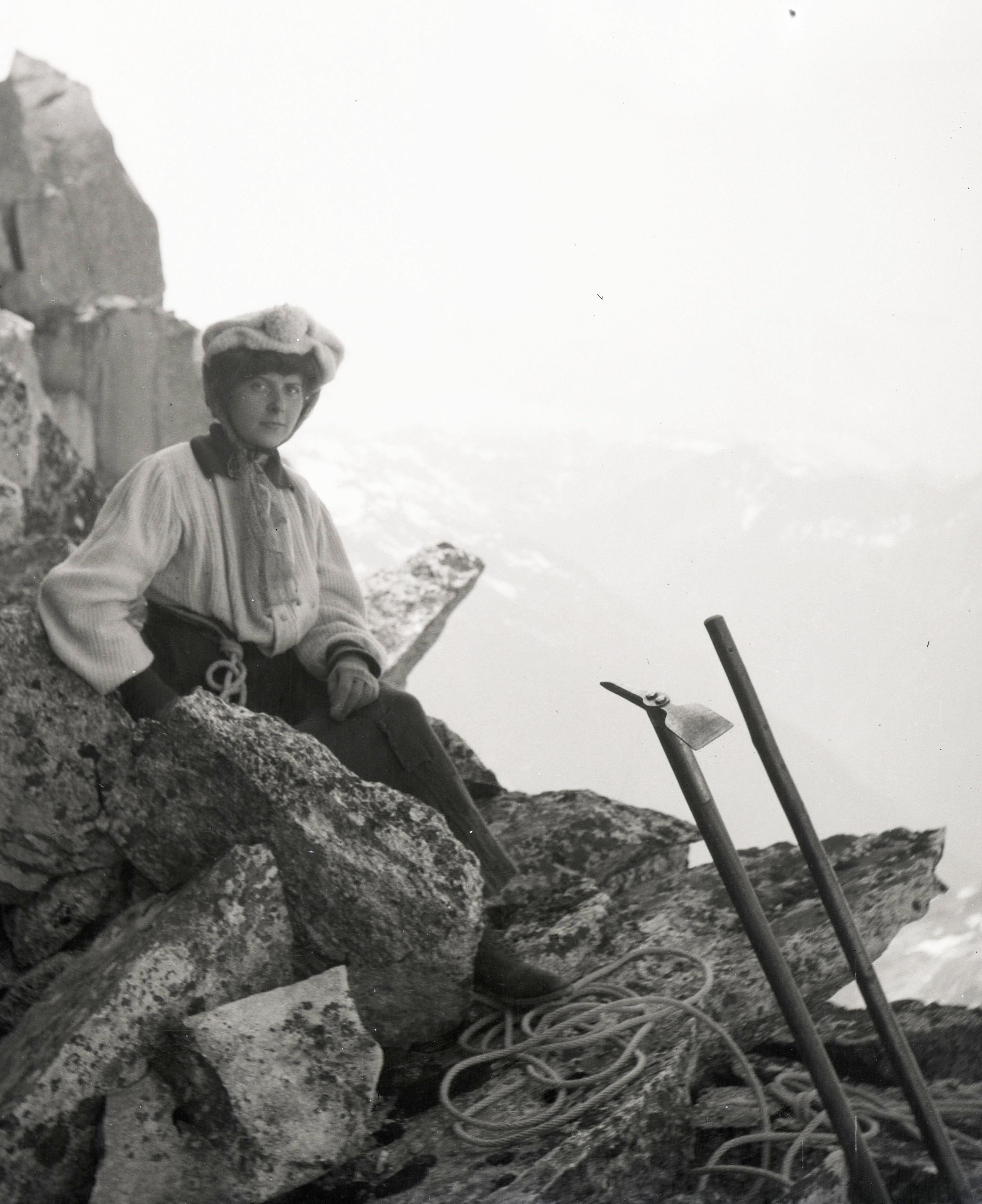

High on the mountain, light snow continued to fall until about 1 a.m., and then, as the skies cleared, the temperature dropped into the lower 20s (F). Their sodden clothing froze hard and their joints turned stiff. They had found no gear placements, so they had no anchor. Afraid to even stand up for fear they might fall, they stayed put. The two were so miserable and scared that they each called parents and siblings to say good-bye, thinking they might die before sunrise.

By 3 a.m., rescue teams started to arrive at CCSAR’s base in Westcliffe. An hour later, over 20 mountain rescuers from four counties were hiking toward the base of Ellingwood Ledges. All the while, CCSAR liaised with the National Guard to coordinate a helicopter extraction utilizing two Alpine Rescue Team hoist rescue technicians. Weather conditions were questionable, and it was not until well after sunrise that the helicopter mission became a “go.” After a 130-mile flight, Black Hawk 529 out of Buckley Air Force Base arrived overhead at about 9:45 a.m. and determined a hoist insert and extraction was possible.

Two rescue techs were lowered to the stranded climbers. Other than being very cold, stiff, hungry, and thirsty, the climbers were in remarkably good condition. The morning sun had thawed and dried their clothes, and warmed their spirits. The two were helped into rescue harnesses, and when the Black Hawk returned, the climbers and rescuers were hoisted two at a time and flown to CCSAR’s base in Westcliffe. By 2:45 p.m., all the ground teams had returned safely to Westcliffe, ending a 22-hour mission.

ANALYSIS

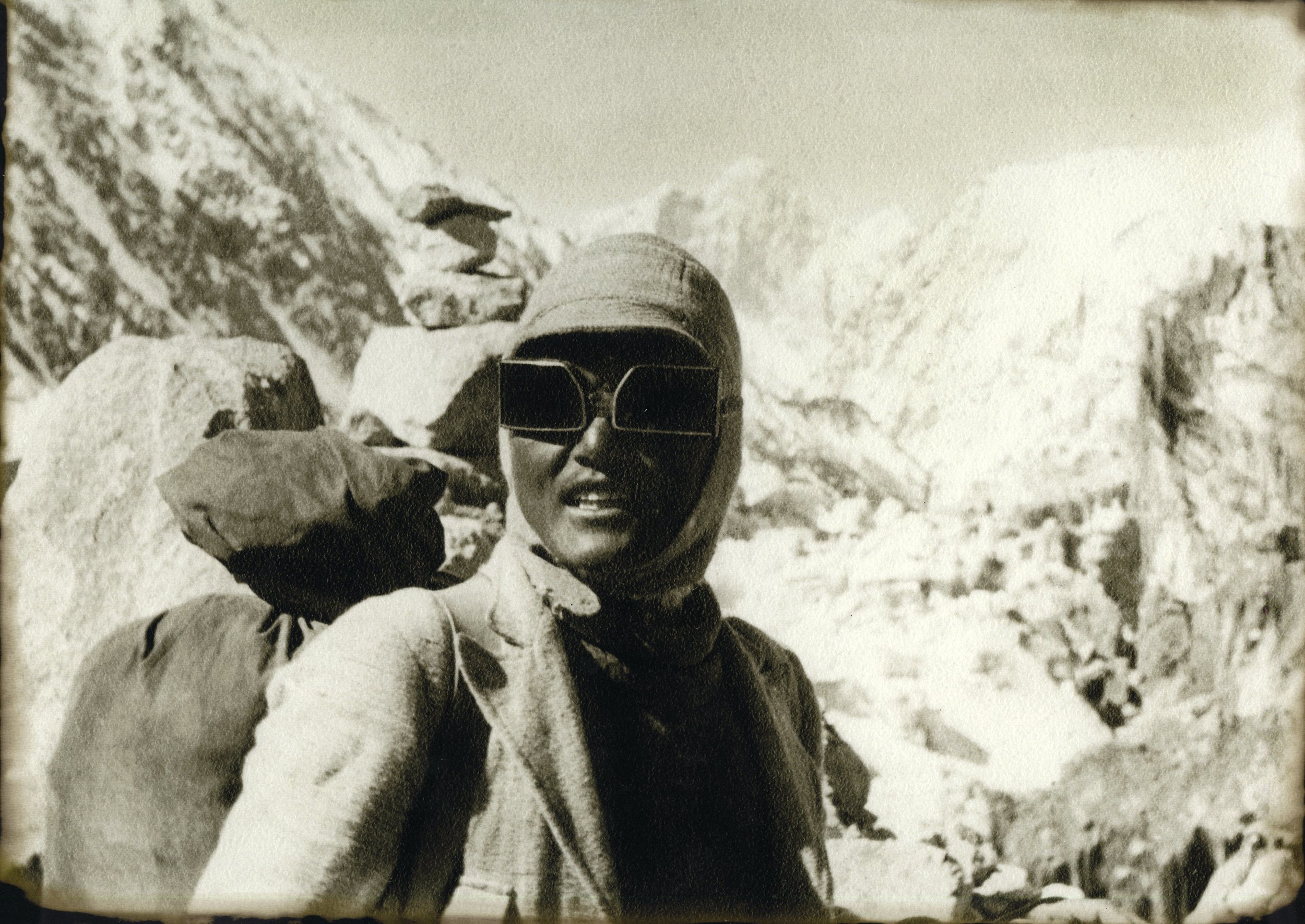

The two climbers were capable multi-pitch crag climbers who aspired to do their first alpine or big-mountain route. They had the skill to climb this route in summer conditions; however, the preceding winter had been one of Colorado’s snowiest in many years. Though the calendar said early summer, snow and ice on the high mountains was similar to mid-May. The arrival of the storm only worsened the situation.

The storm had been well forecasted for the mountains, but the pair did not get the right forecast. Many phone apps present weather for nearby towns, so the climbers got the forecast for Westcliffe, located in the valley to the northeast of the mountain. Then they typed in “Crestone” and another benign forecast popped up—however, this forecast was for the hamlet of Crestone, low in a valley on the west side of the peak. Seeing two good forecasts, the climbers were confident. But there was a very different forecast for the peaks 6,000 feet higher. [Editor’s Note: 14ers.com links to NOAA spot forecasts for each of the Colorado 14ers.]

The climbers had a good alpine rack but left nearly all of it as they rappelled and downclimbed nearly 1,000 feet of snow-covered rock and grass. In their packs they carried shell jackets, beanies, gloves, and good socks—barely enough protection. They climbed in rock shoes and carried light trail shoes for the descent. In a typical summer, these shoes would have been fine, but had they reached the summit, their descent off a very snowy and icy Broken Hand Pass would have been difficult.

To their credit, these climbers kept their wits and survived a miserable night in a very exposed spot. They tried very hard to self-rescue and did a phenomenal job to descend as far as they did.

The role of luck—good and bad—plays a much larger role than we often acknowledge in such situations. In the Sangre de Cristo Range, the weather cleared soon after midnight, leaving the climbers with drying conditions. Further north, in Colorado’s central and northern mountains, the storm continued all night, and upwards of two feet of snow fell. These two put themselves in a place to be lucky when they wisely decided to stop. Surviving a miserable night is always easier than surviving a fall. (Sources: Dale Atkins, Alpine Rescue Team and Colorado Hoist Rescue Team, and Jonathan Wiley and Patrick Fiore of Custer County SAR.)

THE SHARP END: EPISODE 57

Brian Vines was a high school senior and a budding climber in the 1990s when he and some friends went to Sand Rock, Alabama, for a day of top-roping. On their last climb, a simple mistake led to a damaging ground fall. More than two decades later, Brian and hostess Ashley Saupe look back at that day for the Sharp End podcast. Brian has returned to climbing, and his 14-year-old son, J.T., now leads many of their climbs. But the lessons from that day at Sand Rock still guide their every move.

30 YEARS OF ACCIDENT DATA

The September issue of Rock and Ice features an article by AAC member Eliot Caroom presenting a unique analysis of reports in the last 30 years of ANAC (more than 2,700 accident narratives in all). Eliot created a database of keywords to examine the characteristics of accidents in ways not possible with our annual data tables. The results are very enlightening. For example, it’s well-known that many accidents happen during descents (about 32 percent in Eliot’s sample), but his method also reveals that rappel errors were a factor in 29 percent of descent accidents, and another 14 percent involved strandings. Moreover, nearly one-third of all accidents involving a rappel error led to a fatality. Eliot has offered to share his one-of-a-kind database so other researchers can mine this information. Read the story and learn more here.

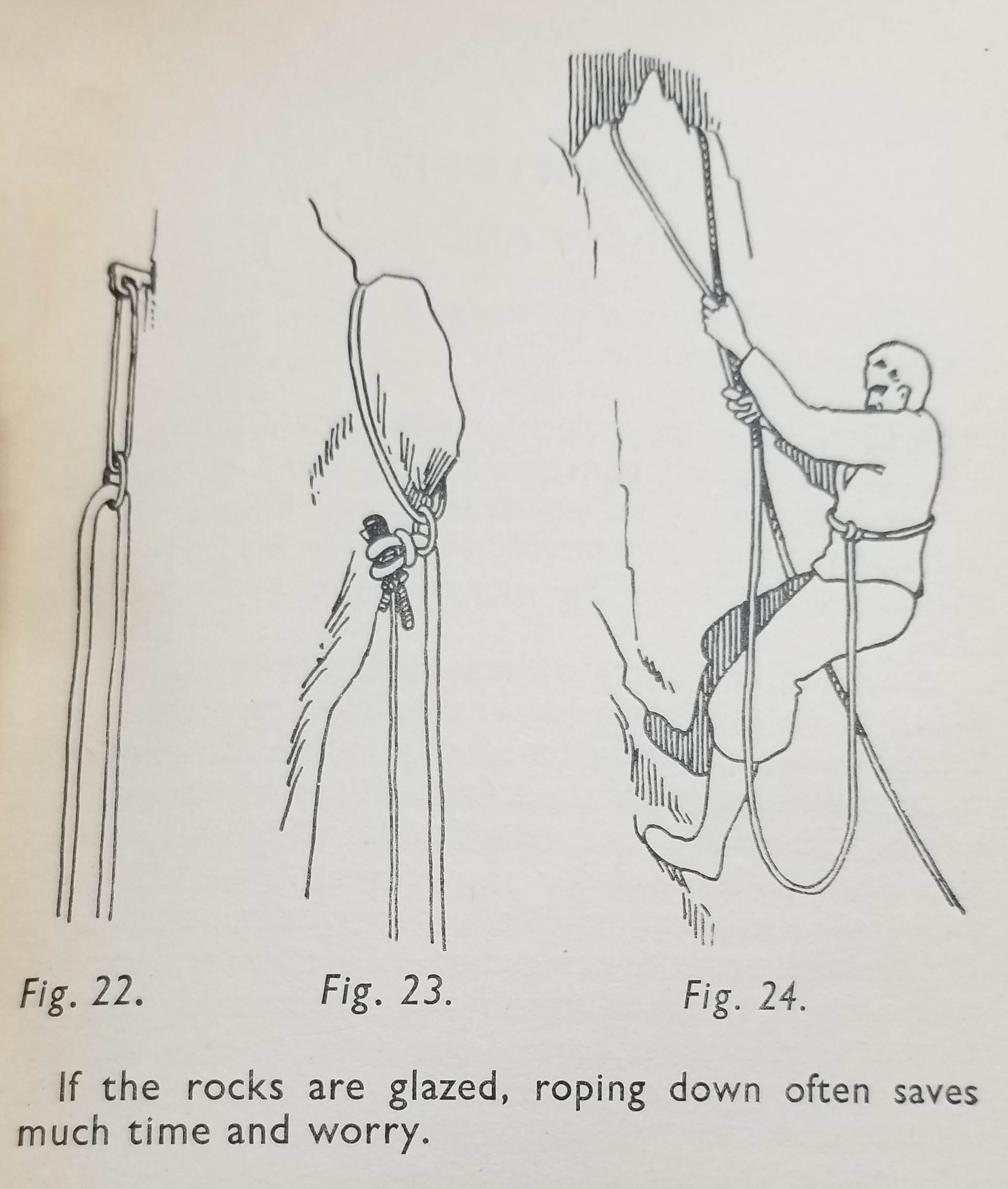

TECHNIQUE TO TRY: PRE-RIGGED RAPPELS

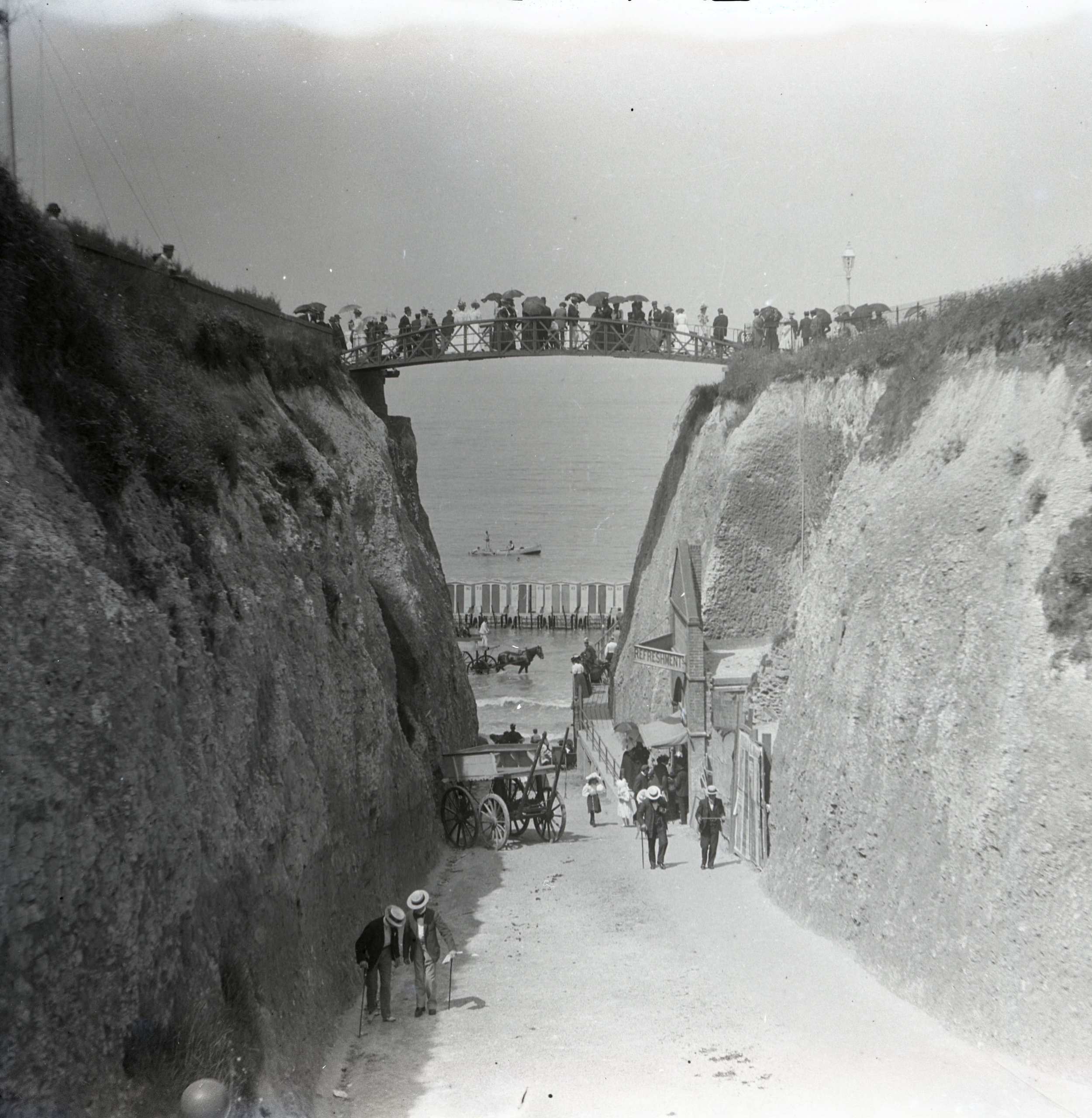

Two rappellers ready to go. Photo courtesy of Alpine Savvy.

Pre-rigging or “stacking” rappels is a technique that is used most often by guides but it also offers multiple safety and speed benefits to any experienced climber. Pre-rigging is when each member of the climbing team attaches an extended device to the ropes at the rappel anchor before anyone begins to rappel. The technique allows everyone to check each other’s rappel setup, and it provides other safety and efficiency benefits, including the fact that only one stopper knot is needed at the end of the rappel ropes. The pros and cons of this technique are well explained in this article at Alpine Savvy.

Pre-rigging is not appropriate for every rappel, and expert instruction is recommended. Once you learn the technique, however, you may be surprised how much you like it for long series of rappels.

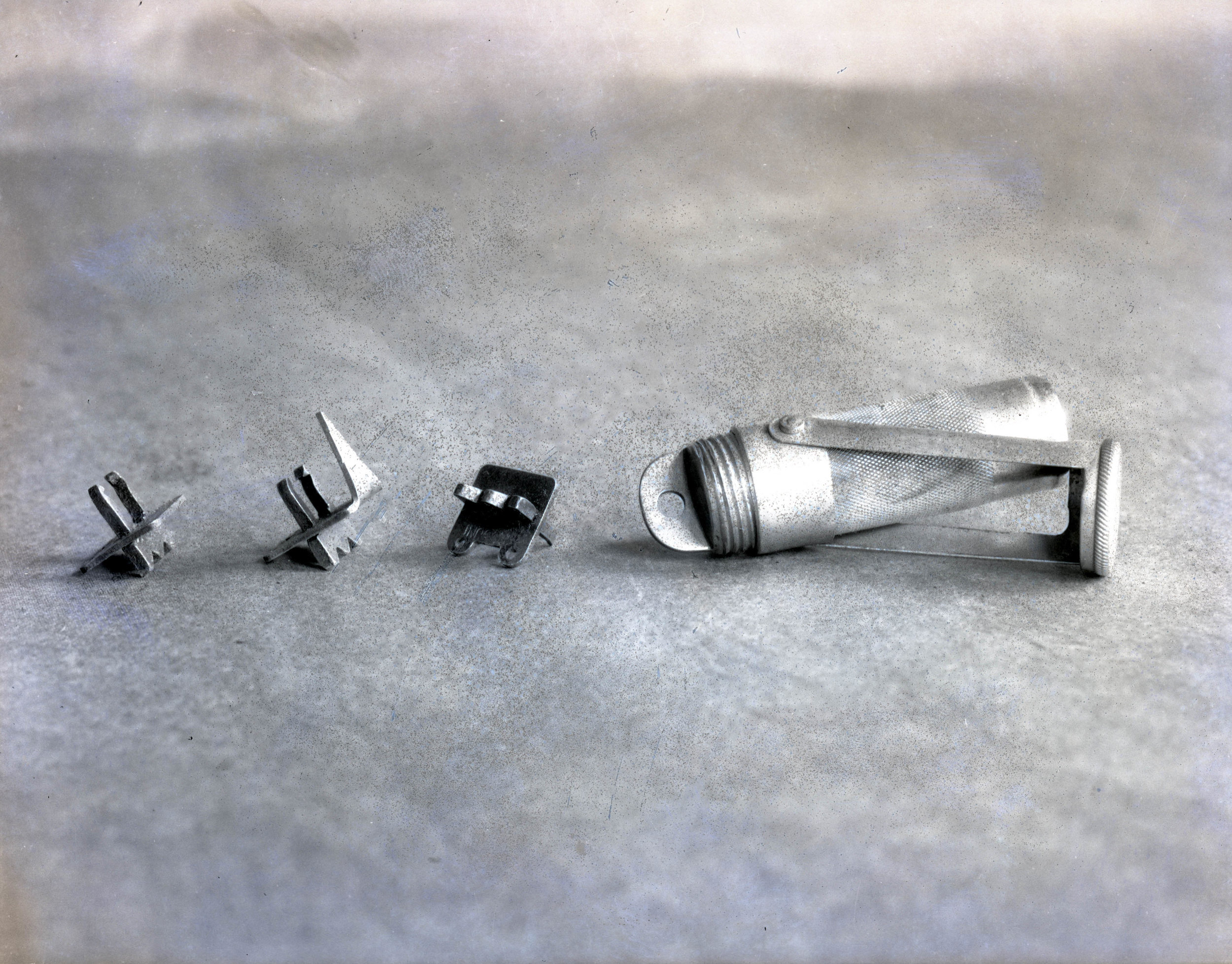

ROPE RECALL

Petzl is recalling a number of low-stretch kernmantle rope after a report that a defective rope was discovered earlier this year. No accidents or injuries have been reported. The recall is a follow-up to a July request for inspection issued by Petzl. The voluntary recall notice, issued by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, is dated September 30 and covers more than 15,000 ropes sold in the United States and Canada, mostly for professional access work and rigging, as well as some caving and climbing applications. The owners of ropes with certain serial numbers are asked to inspect their ropes and contact Petzl if specific problems are discovered.

MEET THE VOLUNTEERS

Lindsay Auble, Regional Editor for Kentucky, Arkansas, and Tennessee

Years volunteering with ANAC: 6

Home crag: Red River Gorge, Kentucky

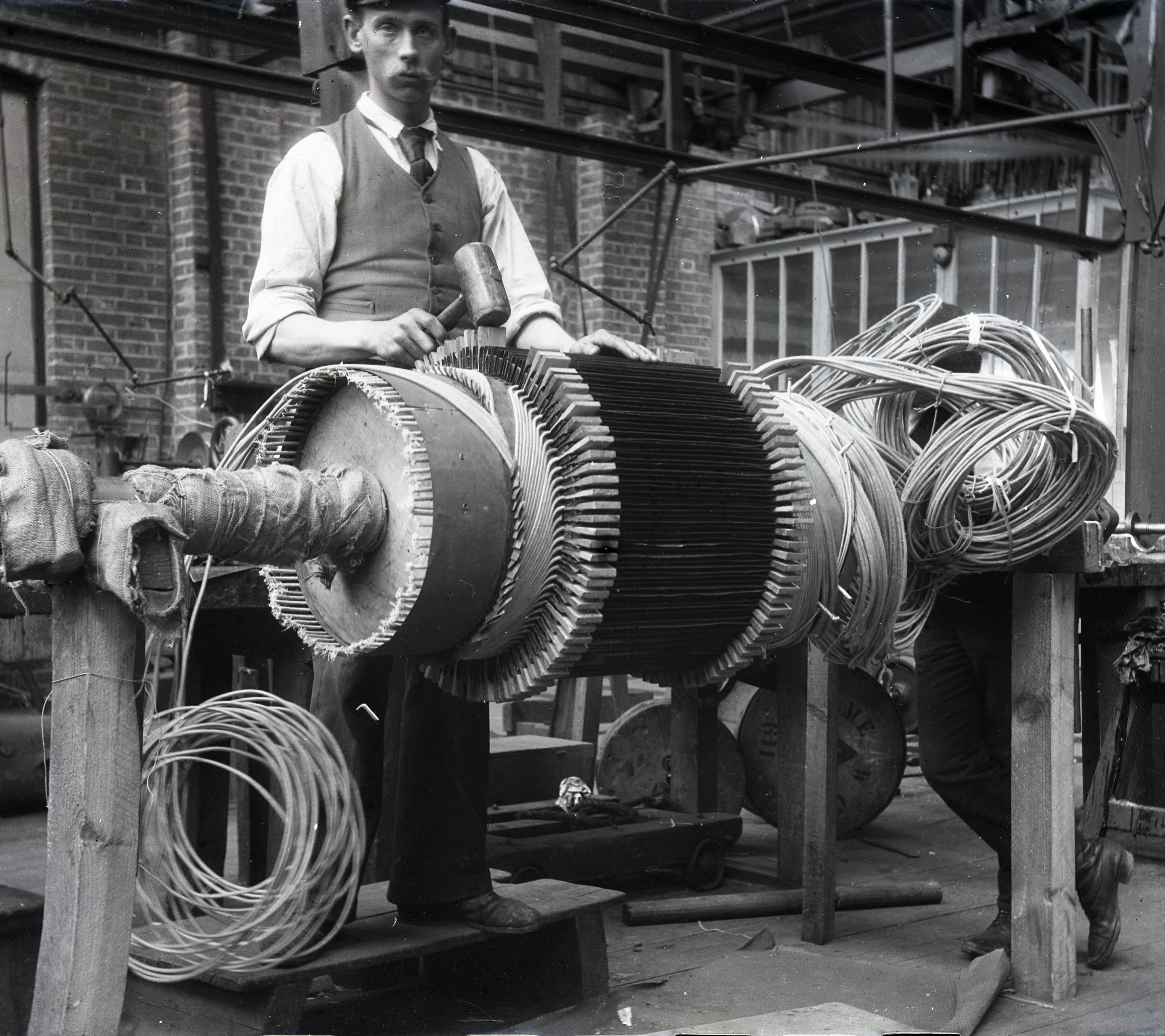

Lindsay at home in the Red. Photo: Johnny Nowell.

Favorite type of climbing: Single-pitch sport. Each season I choose a few routes to project at the very edge of my ability. I love the process of breaking down a climb and training each move. It can be frustrating at first; I can’t count the number of times I’ve said, “I can’t do that move.” But after weeks of problem-solving, training, and engraining muscle memory, the moment it comes together is that much sweeter because of every failed attempt.

How did you first become interested in Accidents?

I started climbing outside in the Red River Gorge and was very lucky to have a strong community of climbing mentors . When I was relocated for work, I asked one of them for suggestions on how I could continue my climbing education, and he pointed me to the AAC and the Accidents publication. Now, every incident I edit is a research project. After I gather the details of the accident, I consult with experienced climbers, guides, and first responders to fully understand why it occurred. We have even set up several situations on practice anchors in the house. In the process of unpacking the “why?”, I have greatly expanded my knowledge of climbing gear and techniques.

Why do you think accident reporting is important?

For a decade, I worked as a chemical engineer, mostly with the construction industry, which is constantly working to improve safety metrics. They found that companies that continuously discuss safety incidents and near misses have significantly fewer accidents. It reminds people of the potential consequences and pulls them out of autopilot, especially when the activity is repetitive. Almost all of the climbing accidents I have analyzed have been at least partially attributable to human error.

Personal scariest “close call”?

While I’ve had an off-route moment with potential consequences that scared every molecule in my being and a low fall that resulted in an injured tailbone, I feel the scariest moments have been a bit more innocuous. Once I hung near the top of a route and then noticed that my knot had threaded only the waist loop tie-in point. I thought, “Huh, this somehow made it through all our safety checks.” Or lowering from a route and realizing that I didn’t remember cleaning it. Kind of like arriving somewhere and not remembering the drive, because you’ve done it hundreds of times. So scary!!

Personal safety tip?

After an accident that devastated our community, we are getting in the habit of weight-testing the system before leaving the ground. After our regular safety checks and stick-clipping the first bolt (a must in the Red), both climber and belayer lean back and weight the system, loading the knot and engaging the belay device. In addition to serving as a demonstrative check of the system, this method has the added bonus of tightening the knot and removing a little stretch in the rope to better protect a low fall.

What is your favorite thing to do when you are not climbing?

I’m a huge fan of puzzles and games. If there is such a thing, I might have a clinical sudoku addiction. When my boyfriend and I traveled to Las Vegas, I think we were close to splitting our time equally between climbing and the Pinball Hall of Fame—my boyfriend wins free games and then I use them up when he moves on to a different machine. In fact, we even created a game ourselves: Crag Crushers.

Share Your Story: If you’ve been involved in a climbing accident or rescue, consider sharing the lessons learned with other climbers. Let’s work together to reduce the number of accidents. Contact us at [email protected].

The monthly Accidents Bulletin is supported by adidas Outdoor and the members of the American Alpine Club.