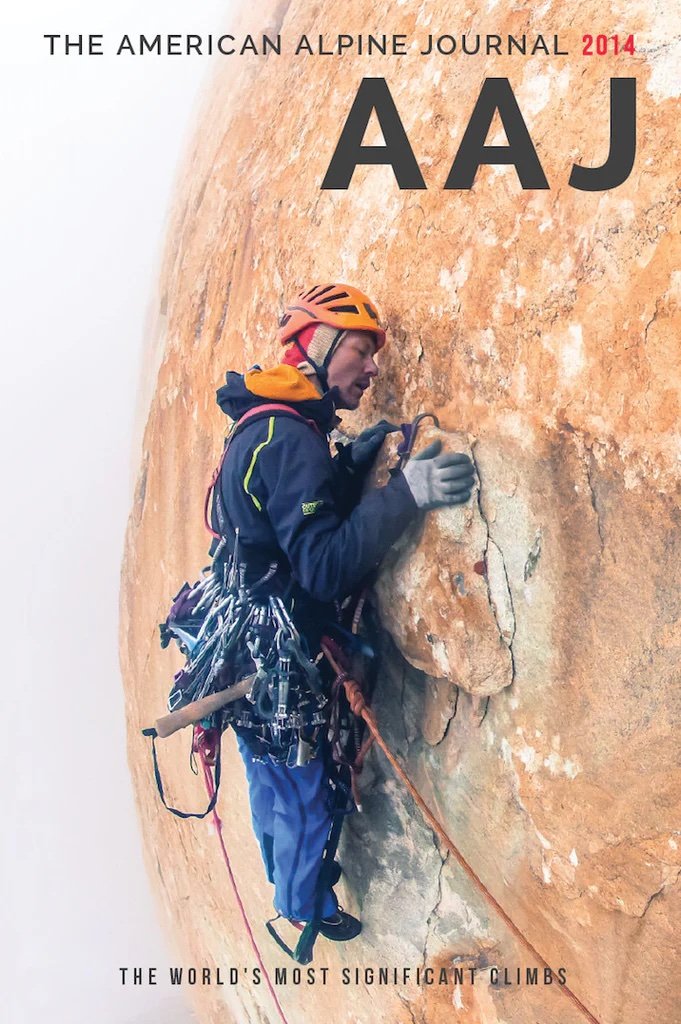

Route Profile: Stoned Temple Pilot, 5.12a, Rumney

By: Ryan DeLena

Stoned Temple Pilot (5.12a) at Prudential, Rumney, NH. Photo by AAC Lodging Director Allyssa Burnley.

It’s hard to find a route quite like Stoned Temple Pilot: a steep, beta intensive masterpiece hidden in Rumney’s Northwest Crags. And appropriately, it's hard to get people to want to walk to The Prudential crag. Most climbers flock to more classic crags, such as Main Cliff, Waimea, and Bonsai. However, if you can talk someone into trekking out there, you’ll most certainly secure a projecting buddy once they experience the epic kneebars, throws, and intricate boulder problems.

I’ve always described the Rumney scene as a culture of beta. Often regarded as one of the most cryptic major sport climbing destinations, Rumney routes are rarely sent on raw power alone. Most climbs can feel a full grade harder until you know the trick to climbing them. The result is a really supportive projecting culture. Once you send, you become part of the crew that can now pass the beta down to the next inquiring aspirant.

Before Stoned Temple Pilot, I was more of a trad climber. I was accustomed to the practice of climbing lots of different routes, and very slowly pushing my limit. Conversely, most people I met hanging out at Rumney had longer term projects they came back to every session.

I first climbed Stoned Temple Pilot while project shopping for my first 5.12a. I was getting to that phase many of us enter in climbing, when the 5.11s start going faster than before and your friends encourage you to get on 12s. I’ve never considered myself much of a grade chaser, but 12a always represented a blockade for me. For years the idea that my body would be capable of that level of climbing seemed outlandish. Finally in spring of 2022, I decided it was time to find a route that inspired me and throw myself at it like never before. I tried a few different classic 12as, but Stoned was the one that captured my imagination.

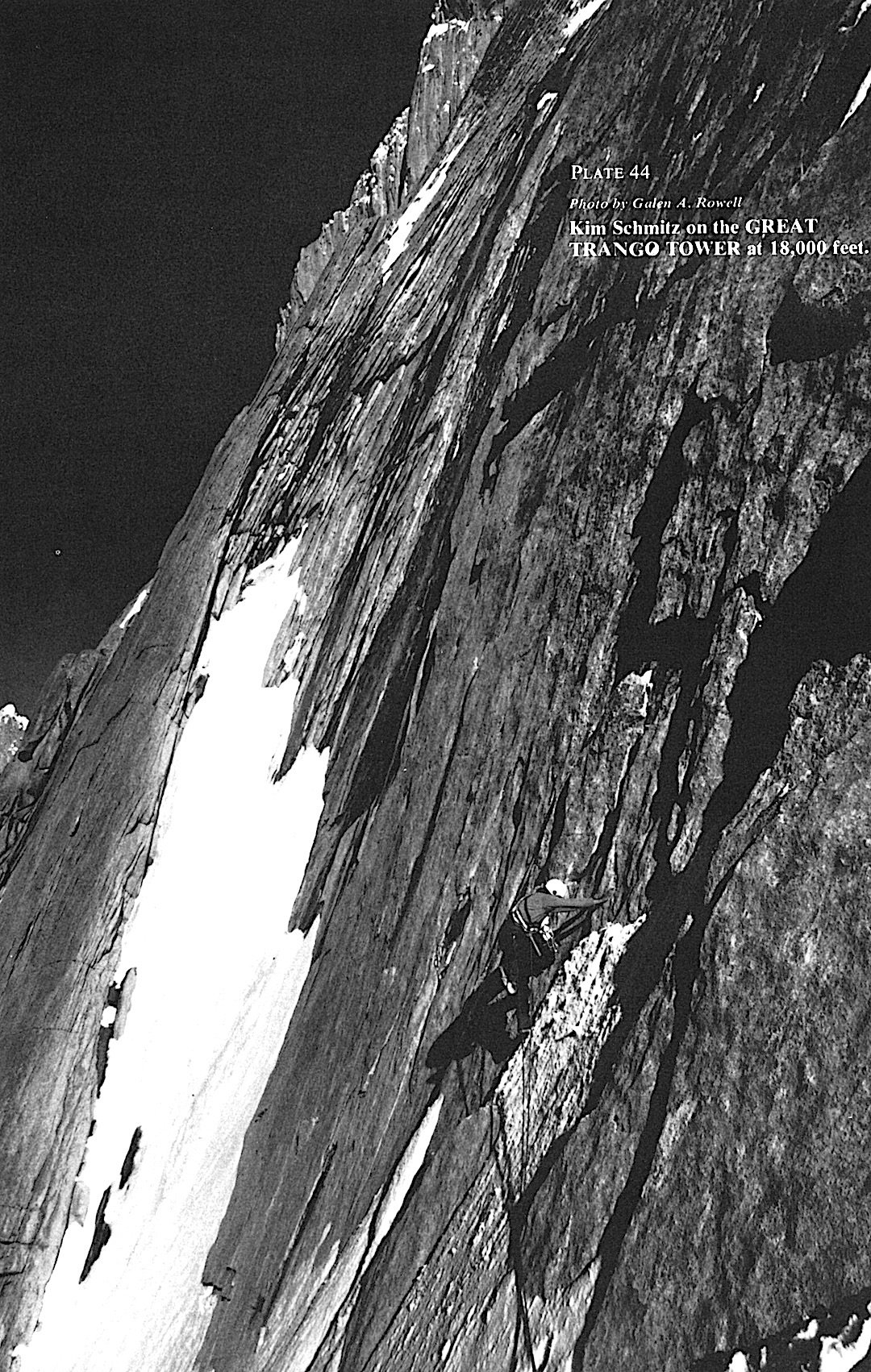

Oh My Finish (5.11b/c) at Orange Crush, Rumney, NH. Photo by AAC Lodging Director Allyssa Burnley.

The route begins with a jug haul through spongy rock, culminating with a double knee bar rest at a monumental hueco. Next comes a bulge, nothing too bouldery, but it saps your energy before the crux. A bad crimp allows you to set your feet and throw. If not for a common tick mark, you might assume you need to make a desperate upward stab into the fat undercling, which is certainly big enough to distract you from the key crimp right above the lip. One more committing move gets you to a sneaky corner rest. If not for meeting a local who showed me this rest, I might’ve abandoned this project a long time ago. As you exit the corner, all the holds seem to face weird directions, but some knee bar wizardry lets you cross to a jug otherwise just out of reach. Made it this far? It’s in the bag.

As I started projecting Stoned Temple Pilot, I didn’t feel like things were going swimmingly whatsoever. On my first burn I did all the moves, then proceeded to never be able to do the top sequence again. I expected to climb the route better with each attempt, but each burn slowly whittled away my faith.

Optimism is something I struggled with a lot my whole life, and climbing forced that reality closer and closer to the surface. Finally I had to acknowledge that somewhere deep down, no matter what I accomplished, I still didn’t believe in myself. Coming back to this route multiple times, somehow getting worse with each burn, was easy evidence to justify the pessimism in my brain.

Two things haunted me. The first: every time I tried to clip from the undercling, I struggled to reach it and pumped out. The second: ever since my project shopping burn, I had not been to the top of the route. Each time I reached the top crux, even after resting in the corner, I failed to recollect how I had climbed it on my first attempt. I would try different sequences that left me hanging on the permadraw over and over, until finally opting to lower. Good links aside, how was I supposed to bring optimism to this route, if I couldn’t clip the crux draw, or even top it out?

One day in June 2022, I discovered the complex relationship between embracing optimism, and letting go of expectations. My friend Mike, and Allyssa, who I had met that morning, walked up to Prudential Wall with me. I had very low expectations. I already had aided my way through a bouldery 11c and my forearms felt fried. The previous day I tried Stoned multiple times and got shut down at the clip in the big undercling. I’d been trying to reach above my head to fear-clip it, ultimately pumping out.

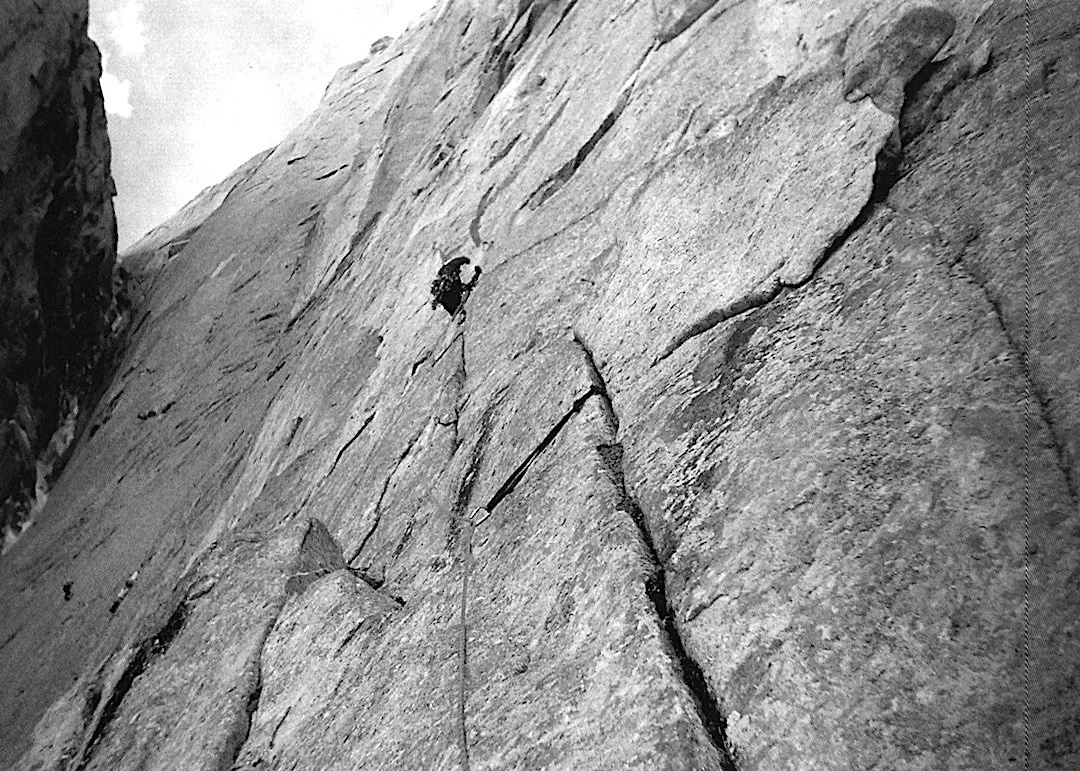

Swedish Girls (5.10d) at Prudential Rumney, NH. Photo by AAC Lodging Director Allyssa Burnley.

As I pulled onto the wall this time, I already planned on falling. I looked down at Mike after the first clip and said, “Man, I wish I was climbing something that used different muscles than yesterday.” Despite the bad attitude, I continued climbing. I entered the double kneebar, this time getting my right hip into the pod and settling into the fetal position, then closing my eyes. This brought a deep sense of calm. I launched into the boulder problem, and stood up into the undercling. Knowing this was where I always fall, I thought to myself, “If I’m going to fall anyway, I should just go for the jug and take the mega whip.” To my surprise, I not only stuck the throw, but had a lot of energy left in my forearms to continue. By simply committing and waist clipping, rather than trying hopelessly to clip above my head from a power-sapping undercling, I completely changed the nature of the route.

I pulled up into the corner rest and stayed there for a long while. I still had not been to the top of the route since the first time I got on it.

I tried to relax every muscle in my body other than my left leg, which held me firmly in the corner. Now with some skin in the game, and determined to send, I launched into the top crux. Completely tunneling into the unknown, I tried something I had not done before. I switched my right knee bar on a sharp horn with a left knee bar, getting my right foot on a seemingly unlikely chip, which gave me just enough height to cross to the big hold.

My heart beating fast now, I clipped the last bolt, and pulled through the final moves audibly in disbelief.. I screamed with joy. Through the sneaky art of low expectations, I had proved my potential to myself. Climbing some elusive grade wasn’t about having Herculean strength, it was about mastering the sequence.

I’ve since sent a number of 5.12s, and all of them started like Stoned Temple Pilot. They felt so unbelievably impossible, until one day they didn’t. I’d come back fresh, with refined beta, and flow through the sequence like butter, because knowing the way is far more efficient than trying to muscle through.

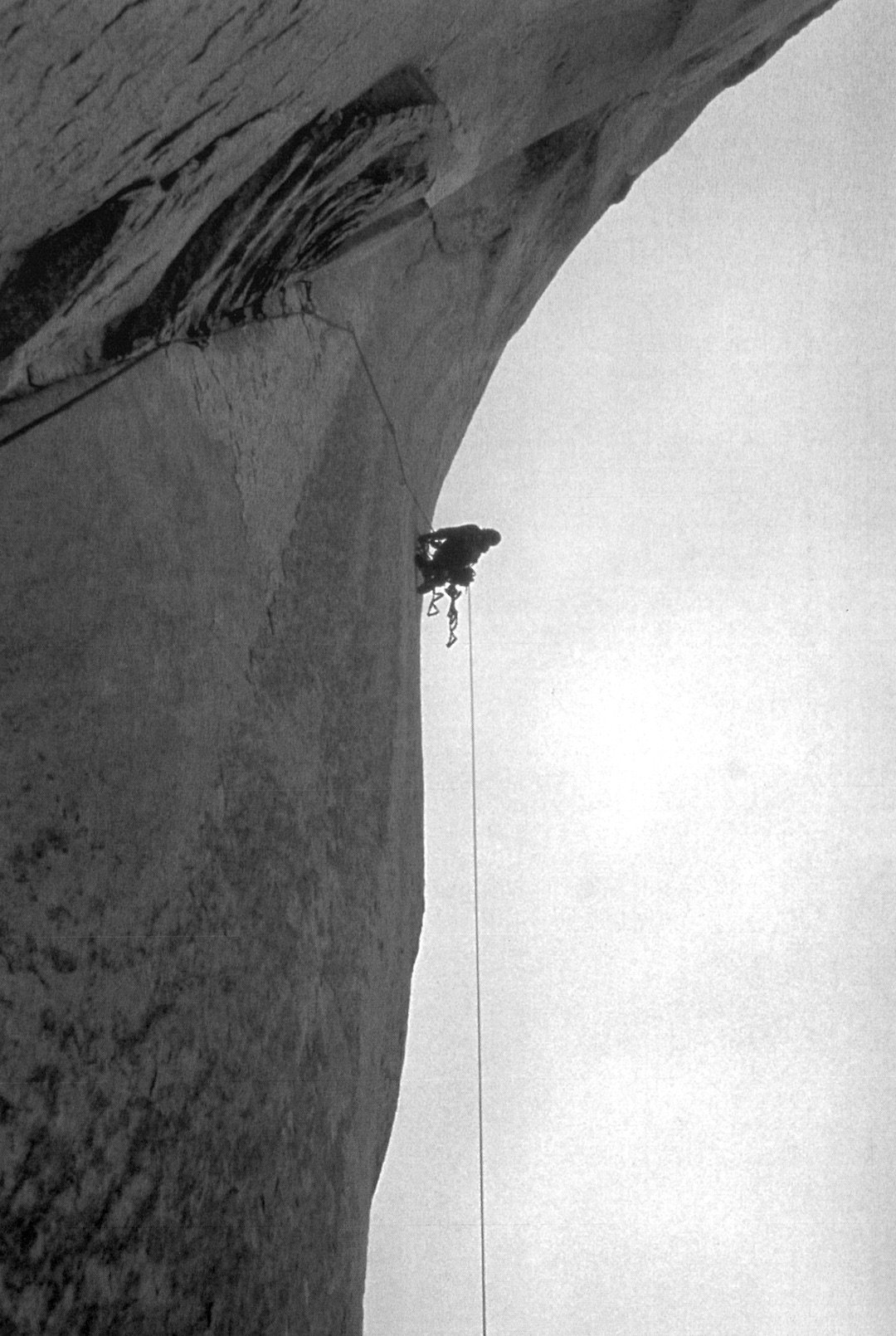

Black Mamba (5.11c) at Orange Crush, Rumney, NH. Photo by AAC Lodging Director Allyssa Burnley.

Though my brain is awfully resistant to change, going through this projecting process a number of times now has helped me embrace optimism more in my life. It reminds me that the whole idea of optimism is believing what’s coming will be better, despite not having the evidence to prove it. If you have proof, you don’t actually need to believe in anything. The projecting process reminds me that things can still go my way, even if it feels like that’s impossible, and the act of believing is often the first step in changing impossible to possible.