Early in the project, Omar Gaytán emerged as a leader : He is a talented climber and candidate for a master’s degree in translation and interpretation, and was incredibly dedicated to the Accidents translation. He’s also co-creator of a cool Mexican climbing podcast, La Mera Beta. We asked Omar, el jefe of this project, to tell us a little about himself:

I’m Omar Gaytán from Juárez, Chihuahua, México. Thanks to my dad, basketball was all I wanted to do throughout my childhood, because my dad loves to play it and he’s also a huge fan of the sport. When I was 15, I discovered climbing—I’m 30 now, and I don’t think I will ever stop climbing. I just love it so much.

I studied in Juárez until I went to college in El Paso, Texas. I majored in communications with a double minor in translation and French, then moved to Guadalajara to study for a master’s degree in translation and interpretation. The reason I chose this career comes from my very first trip to Hueco Tanks back in 2006. I was 15 and I remember looking at some smiley dirtbags working on their computers before spending the day climbing. Their smiles made me realize that I wanted to dedicate my time to something I love and at the same time make a good living—yes, that’s my personal interpretation of the American Dream.

I’ve been lucky to climb at many different areas in the United Sates, and in México I know pretty much all the major climbing destinations. The climbing I like the most is near my hometown, Juárez. The sport climbing here is amazing and still blooming. I feel like I still have a lot to learn about climbing, and that’s exactly the aspect of both my climbing and my career that I love the most: You never stop learning and growing. I’m becoming a better translator every time I translate documents, the same way I get better at climbing every time I send a project.

I feel happy to have been able to collaborate with the American Alpine Club on this project. There is nothing better than working on something you love so much, and, on top of that, spread the word about safety in climbing. I am forever thankful for this opportunity, and I hope we only get better at this in the years to come.

STORIES FROM MÉXICO

Mexico is part of North America, of course, but it hasn’t always been a big part of Accidents in North American Climbing. One side benefit of this translation project, we hope, will be increased access to information about climbing in Mexico and other Spanish-speaking areas of North America, including Puerto Rico. In this way, we hope the AAC can help climbers learn more about both the opportunities and hazards in these beautiful areas.

The upcoming ANAC 2021 includes a single report from Mexico, a tragic story involving two U.S. climbers and an unusual accident on a big wall in Chihuahua. Here’s a preview.

Ledge Collapse | Severed Rope

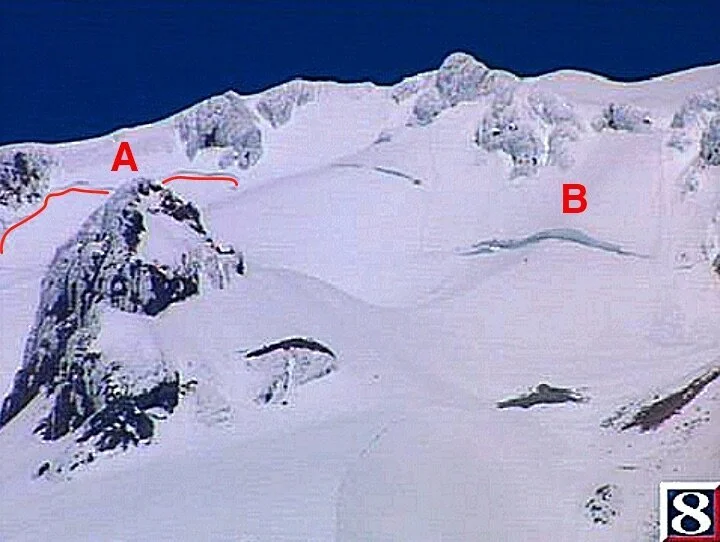

Chihuahua, Basaseachic Falls National Park, El Gigante

On March 6, my best friend Nolan Smythe, 26, and I were on the second day of a free ascent of Logical Progression, a 28-pitch 5.13 big-wall sport climb on El Gigante. Nolan was leading pitch 14. The sun had just gone down, and we had two moderate 5.11 pitches to go before our next bivy. He made it about 80 feet into the pitch and then, after manteling onto a large ledge, the refrigerator-size block of volcanic rock dislodged from under his feet. As he was falling, the rope was cut by the huge block and he fell all the way to the ground.

I was left alone on the wall with a shortened lead line and a limited number of draws. A three-day storm was forecast to start the next afternoon. Below me was a sizable traverse that I wasn’t confident I’d be able to descend safely while keeping my bivy kit. On top of that, we had rappelled in to start the climb, and I didn’t know the walk-out exit for the canyon; this exit route also passes very near several poppy fields run by the local cartel.

Instead, I started roped soloing up to our planned bivy. I primarily used a stick clip, but on occasion free climbing was necessary. I alerted a good friend, Sergio “Tiny” Almada, about the situation via my inReach, and he started toward the wall with another Mexican climber, José David “Bicho” Martinez, planning to rappel in so I could jumar the last 1,200 feet to the top. They arrived as the rain started, and we left my kit behind to jug out quickly. We returned a week later, after the body recovery, and cleaned all of my gear off the wall.

ANALYSIS

All told, this seemed like a freak accident more than anything else. I recall rappelling past the same ledge earlier with a large haul bag. It looked concerning, but after giving it a thorough test, I deemed it solid. Nolan must have had the same thoughts during his lead. It had been snowing for three days before we rappelled in, and this accident happened three days after the snow stopped. It is possible that a freeze-thaw cycle contributed to the rockfall, but there is no way of definitively knowing. Sometimes a rock that many people have pulled on has a day that it is going to release. Unfortunately, it released on Nolan.

Don’t underestimate Logical Progression because it’s a “sport route.” This wall is remote, large, and committing. The weather can be really bad. Be prepared. You are on your own out there—help in case of an accident isn’t as close as you think it is in Chihuahua.

We were prepared with bivy gear, a stick clip, extra draws, an inReach, and the knowledge to go up or down the wall safely on our own. Nolan and I were both well within our comfort level. We both had quickly dispatched the first 5.13 pitch on the route on the morning of the accident. Some accidents are simply a matter of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. (Source: Aaron Livingston.)

The Optimist